Reviewed by Leslie Lindsay

“Here’s an old scrapbook of your grandmother’s. Do you want it? The photos have been removed.”

“Here’s an old scrapbook of your grandmother’s. Do you want it? The photos have been removed.”

This is a personal snapshot from a conversation with my own father, a simple gesture in which an entire manuscript is being conceived.

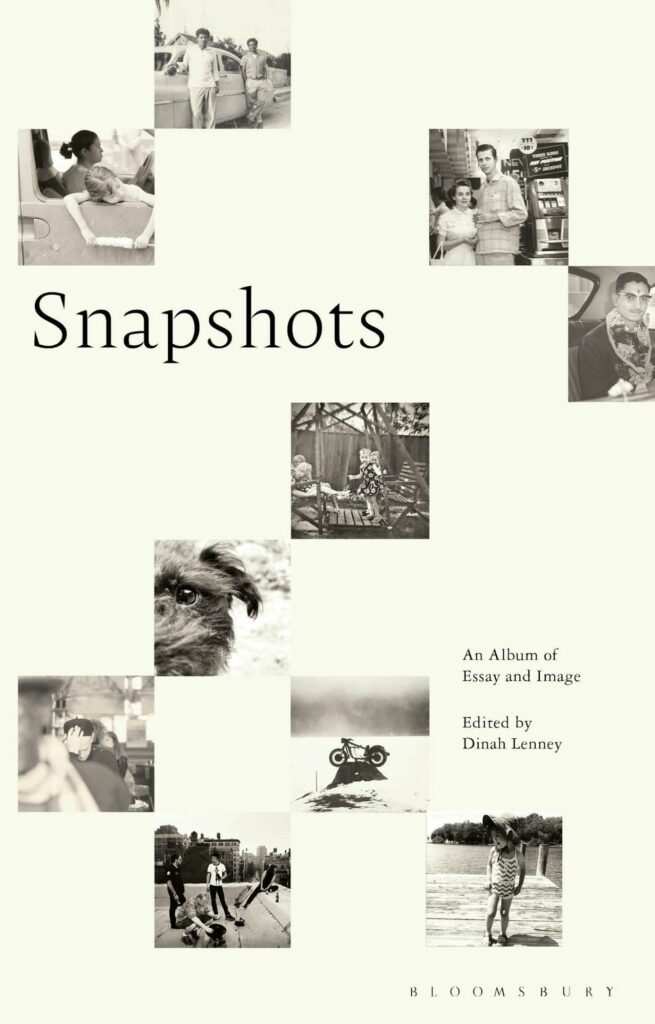

In Snapshots: An Album of Essay and Image (Bloomsbury Academic; 2025), editor Dinah Lenney presents 36 provocative, intimate, genre-fluid micro essays by a diverse and powerful cast of writers on aging, appetite, childhood, death/grief, personhood, motherhood, reality, time, space, immigration, obsession, and so much more.

Unlike the album from my grandmother, this ‘album’ is not empty. It would be difficult to identify aspects of the human condition that aren’t in some way touched, or glanced upon, by these ekphrastic pieces. The images in Snapshots have been drawn from each writer’s personal archive, but each are presented in black and white, which brings to mind a classic, nostalgic, and dynamic translation. Black and white work is an important marriage of luminous, well-crafted, and thoughtfully composed imagery. Here we are involved in a sort of dialogue with history and tradition, but in a modern voice.

In exploring their subjects, contributors make use of unexpected references to imagination and description, which at times invites the reader to interpret and interrogate the image along with the writer, the pieces in turn become a type of conversation between writer, reader, and photo. Or photographer, which is a separate entity from the final product: the photograph.

What Snapshots does so well is interrupt the concept of ekphrasis, which is not simply a written account or description of a visual piece of art (sculpture, painting, photography, etc.), but it moves within and beyond the frame. For example, in Sonja Livingston’s “Vigilante,” we are introduced to a young girl with a mop of dark hair wearing a fringed shirt and pointing a toy gun at the camera. She’s squinting her left eye. It could be Halloween. It could be the end of the essay. It’s not. This is precisely what writers do: they expand and extrapolate. Livingston takes us into her hardscrabble childhood from this photo alone, “Here’s the shame of food stamps and the child brave enough to use them.”

And in Alex Marzano-Lesnevich’s “The Distance,” we are brought into the nebulous concept of time, how it is at once happening now, but also later, and in the past: “Time, maybe. Morality, maybe. That this had taken you your whole life so far. That if you were to feel, you were going to have to be hurt.”

But it’s not always about feeling, although so many of these pieces are. It would be difficult to tease out any emotion from any of these essays, because, they contain multitudes, which we are acutely aware of their subjectivity, like in Lynell George’s “Off Map,” in which she discusses a paper courtesy map offered by a hotel, how a “brief squiggle of a pen down Charles Street connects nothing to nothing, how it floats from here to there, without being present or future.”

Kate Carroll De Gutes uses a photograph of four little years all wearing the same floral sundress as a point of entry to the photograph that came before, in “Girl by Default.” Of course, there’s the metaphor. What if all photographs were discussed in terms of the shot that came before? And is ‘before’ the same as ‘first?’

Snapshots, like the empty scrapbook of my grandmother’s, has captured a body of work–a record—of what has been left behind. These authors have interwoven imagination with fact, speculation with fiction. They have dipped into poetry and conversation. Regarding matters of “truth,” one can never know with any degree of certainty.

Aisha Sabitini Sloan’s piece, “What’s in The Background,” brings the line, “People respond to the body before they respond to the camera,” and speaks boldly about whiteness and blackness. It’s a conversation between the author and her father about Paris and a visual dialogue, what the image proves, or erases.

When one of the last essays, “Girl With Corn,” by Dinty W. Moore, ends with “I hope she is doing well,” I am immediately jarred and recollect a collection of vintage postcards from ancestors in my possession.

Wish you were here. Hope you are doing well.

As Moore writes, “For every photograph we see, in our family albums, in a gallery, on our phones, there is a moment after the photograph was taken. And the moment after that. And the following day. And decades later.”

Throughout these 36 pieces in Snapshots, one senses a theme, and as the late Judith Kitchen used to say, ‘it’s the readers, not writers, that come up with themes,’ but there are certainly some shared characteristics that repeat and alternate throughout, particularly identity and emotional boundaries of being, which harkens back to the definition of ekphrasis: is it art about art or a whole new creation?

Snapshots is not only an intriguing, thought-provoking collection of affective essays for anyone interested in the possibilities of genre, be that hybrid, poetry, ekphrastic work, photographic studies, or memoir, but it also might very well qualify as a masterclass in the form. Not every anthology offers suggestions for further reading or photo prompts as this one does.

Finally, I’m scrolling through my camera roll. I’m picking and choosing, making it up. I’m curious what came before and what will come after, when I close this digital scrapbook, what will my grandchildren choose to keep?

Leslie Lindsay

Staff InterviewerLeslie A. Lindsay is the author of Speaking of Apraxia: A Parents’ Guide to Childhood Apraxia of Speech (Woodbine House, 2021 and PRH Audio, 2022). She has contributed to the anthology, BECOMING REAL: Women Reclaim the Power of the Imagined Through Speculative Nonfiction (Pact Press/Regal House, October 2024).

Leslie’s essays, reviews, poetry, photography, and interviews have appeared in The Millions, DIAGRAM, The Rumpus, LitHub, and On the Seawall, among others. She holds a BSN from the University of Missouri-Columbia, is a former Mayo Clinic child/adolescent psychiatric R.N., an alumna of Kenyon Writer’s Workshop. Her work has been supported by Ragdale and Vermont Studio Center and nominated for Best American Short Fiction.