Interviewed by Morgan Baker

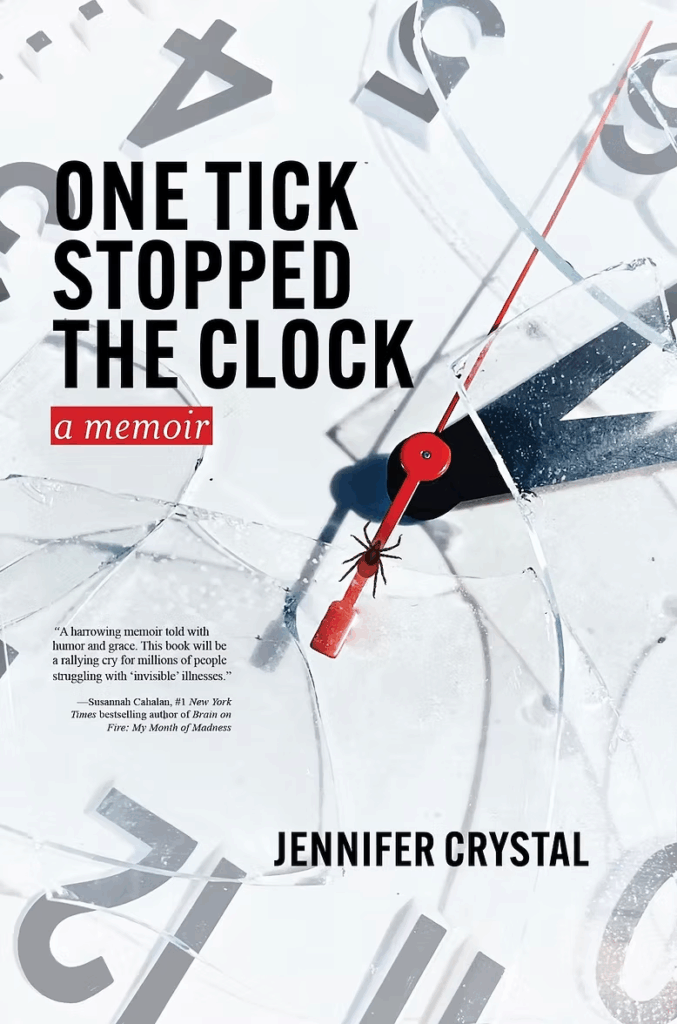

In 2013, my department chair at Emerson College asked if I would be interested in working with a grad student on her memoir. I said yes, immediately. That student was Jennifer Crystal, author of One Tick Stopped the Clock.

In 2013, my department chair at Emerson College asked if I would be interested in working with a grad student on her memoir. I said yes, immediately. That student was Jennifer Crystal, author of One Tick Stopped the Clock.

Many years later, I sat in the audience at Porter Square Books Boston to listen to her read from the book at her launch. Jennifer’s book is about her struggle with Lyme and other tick-borne diseases: how it was missed in 1997 when she was a counselor at a camp in Maine.

For years, she endured a myriad of symptoms such as Mono, Epstein-Barr Virus, sinus infections. She pushed through so many of these so she could move to Colorado, but after a year there, she came back to Connecticut. It took another two years to find a doctor who knew Lyme disease, and another several years of treatment for Jennifer to get better.

Recently, I was excited to talk with Jennifer on Zoom about her writing process for One Tick Stopped the Clock.

Morgan Baker: One of the things I tell my students is that their stories – essays and memoirs – can be about them, but often the stories do represent a bigger theme or issue. Your book did that. While it was about you and your journey with Lyme disease, it’s really about living with chronic illness and how that affects both the patient and those who love that person.

Jennifer Crystal: Thank you. That means a lot, especially coming from you, because I worked with you in the beginning. You really got me going on this book. So, I really appreciate that feedback.

MB: Well, I had fun working with you on it. It’s exciting to see it all here in a book. So, you started it in 2011.

JC: 13 years.

MB: Why do you think a book takes that long to write? I’m not saying like, “Oh my god, what took you so long?” But they often do take that long.

JC: I think there are a couple of reasons. There’s the practical reason – usually writers can’t just sit and write. They have to do other work. I do other things, and other parts of my life that take up brain space. I started the book in grad school, but even then, I was taking other classes and reading other people’s work. But I think the larger issue is that it takes time to gain perspective on your own story. Even if I had finished a full draft when I was in grad school, I wouldn’t have been able to have as much reflection in there. I just wouldn’t have gained enough perspective on my own story. It took many revisions to get to that. Speaking to the larger story of chronic illness, that really got folded in during the pandemic.

COVID happened, and there was the larger story.

MB: It’s interesting that oftentimes you think the book is done. But it really isn’t.

JC: I was so excited when I was working with an interested agent, and wanted it to sell, but I’m so glad that version didn’t, and this is the version that’s out in the world. This feels like the right version.

MB: What prompted you to start writing the book?

JC: I wanted two things. One was to process my own experience. I had used writing as a healing tool previously, but moreover I had the desire to share what it was really like, with Lyme disease and invisible illnesses. I wanted to share both for the lay public, and also to help foster understanding about Lyme and other chronic illnesses. I wanted patients to feel seen and validated.

MB: One of the things I appreciated in the book was the scene building you did. How did you know when, where, and how?

JC: Writing in grad school, you probably helped me with this too in the chapters we worked on. You encouraged me to include scenes and think about where to include and why. There were a lot of scenes I wrote in the beginning that didn’t make it into the book. I tell my students that is an important part of the process. I had to see what actually had to be used, what actually needed to be shown.

Richard Hoffman told us, slow down, bring us into the scene. One of the things I talk about with my students is how a good writing-to-heal piece needs both action and reflection. Teaching definitely informs my writing more than anything else. You probably experience that as well.

MB: This should not have come as a surprise to me, but I thought, oh my god, she was sick for so long before anybody figured it out. As hard as everything was, there was also hope in the book.

JC: That’s what I wanted. I wanted to be truthful. I didn’t want to give false hope, and that everything was tied up neatly, because that’s not what happened. It was so dark for so long, but there was this hope. And it did get better. You can still grow up and go on to create a meaningful life in the context of chronic illness even if you can’t go back to the life you had previously.

MB: Can you talk a little about how chronic illness is often misunderstood? You put in some scenes with your mother and then with your father and stepmother. I wonder how they felt when they read this, particularly the scene when your mother loses it.

JC: They actually read an earlier version which had more of them in it. I then revised it down. I didn’t need to show them as much. My mom read it a lot. She’s a former English teacher. She really helped me with the final revision, which was a pretty big one.

MB: I tell my students that if they’re going to write about somebody, you need to put yourself in their shoes and you need to write with compassion. I think you did that. The other thing you did well was to show how people don’t always listen to the patient, but they will listen to a doctor.

JC: That was frustrating. Even when my dad and stepmom go to the conference, and they come flying in the door and announce, “You really have Lyme disease.” That’s what I’ve been trying to say. But they’ll be the first to tell you that conference was their “aha” moment… It had to come from doctors. At the conference they met Lyme doctors and a lot of patient families. They realized lots of people out there were going through the same thing. It normalized it for them.

MB: This resonated with me because we have a family member with an invisible chronic illness and I heard myself in some of the things your parents said. It was a good slap across my face.

JC: That was my hope that including those scenes, I wanted to show what it’s like to not have agency or to be believed. There were so many others, but I wanted to just pick a few that illustrated that.

MB: The scene when you are driving across the country, and you just can’t do it anymore was so on point that people with invisible illnesses often think they can just power through.

JC: I wanted to show that too. That was my mentality that it’s better to do that, but think I literally crashed. In our society, you’re supposed to be successful. You’re supposed to keep going. You’re supposed to power through. There’s no time to be sick.

MB: You mentioned in the acknowledgements that Doug Whynott helped you with the structure. And I’m wondering what structure you did use, because I don’t know if this was the intention, but it was a page turner.

JC: That’s the greatest feedback. I like hearing from patients who feel seen on the page. The greatest and most surprising feedback I’ve gotten from general readers is they thought it was a page turner and couldn’t put it down. I didn’t expect anybody to say that about it.

MB: You chose to put a prologue in. That’s always a tough decision. Can you tell me how that came to be?

JC: I really liked Susannah Cahalan’s Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness, and thought about how I could model mine after that. I thought about what I wanted the hook to be. Ultimately it came back to when I found the rash, but didn’t know its importance.

MB: Where are you now? You’re a teacher.

JC: I have to thank you for connecting me to Grub Street. I truly feel like I ended up doing exactly what I was meant to be doing and teaching exactly what I’m meant to be teaching Writing to Heal. I first did it at Middlebury for the January winter term. Then I did a couple at Grub Street. Then we got a following, so I created Writing to Heal 2, an advanced course. Now we have an immersive program – a 6-month program you apply to.

MB: How is your health these days?

JC: I still have to take a nap every day. I wish that wasn’t the case, but it is right now. But I would say I’m so much better. I’ve just gotten better and better and better. When I’m out and about I’m never thinking about how tired I am. I can ski a full morning now and not even think about it.

MB: How do you think your identity has shifted?

JC: That’s a great question. Who I am at my core is the same Jen Crystal who values close relationships with the people I love and values empathy, and values time in nature, and loves laughing, and spending time with children, and likes to have fun. I’m more identified as a writer now than I was then. I’m a skier again, but I had to wrestle with that. It makes me really happy to have that back in my life.

Morgan Baker writes about reinventing yourself, learning how to handle loss, and emerging from depression in her award-winning memoir Emptying the Nest: Getting Better at Good-byes (Ten16 Press). Other work can be found in the Boston Globe Magazine, The New York Times Magazine, The Martha’s Vineyard Times, Dorothy Parker’s Ashes, Grown & Flown, Motherwell and the Brevity Blog, among others. She teaches at Emerson College and is managing editor of The Bucket. She is the mother of two adult daughters and lives with her husband and two Portuguese water dogs in Cambridge, Mass. She is an avid quilter and baker.

Morgan Baker writes about reinventing yourself, learning how to handle loss, and emerging from depression in her award-winning memoir Emptying the Nest: Getting Better at Good-byes (Ten16 Press). Other work can be found in the Boston Globe Magazine, The New York Times Magazine, The Martha’s Vineyard Times, Dorothy Parker’s Ashes, Grown & Flown, Motherwell and the Brevity Blog, among others. She teaches at Emerson College and is managing editor of The Bucket. She is the mother of two adult daughters and lives with her husband and two Portuguese water dogs in Cambridge, Mass. She is an avid quilter and baker.

Great interview (thanks, Morgan!) and an important book. My daughter has had Chronic Lyme Disease for years but was not diagnosed right away. We knew something was wrong but it was so frustrating and lonely for her to not be truly understood. I was really struck by this comment: “In our society, you’re supposed to be successful. You’re supposed to keep going. You’re supposed to power through. There’s no time to be sick.” Brava, Jen, for speaking up for those who live with silent illnesses!