Reviewed by Sara Pisak

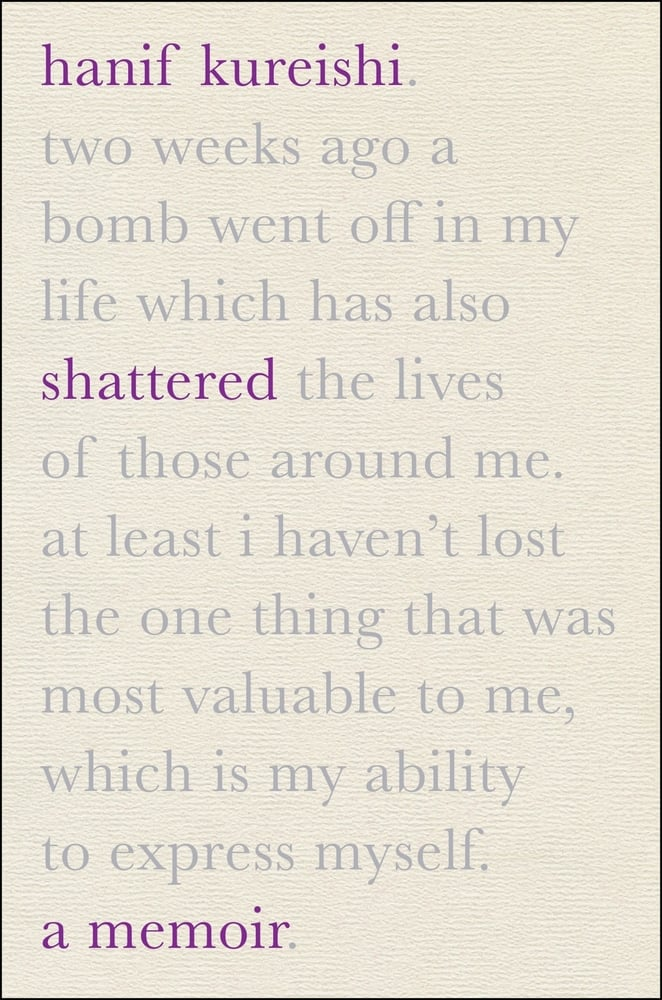

It’s fair to say that after a fall on Boxing Day while in Rome, Hanif Kureishi felt his life and the lives of those around him had been shattered. Both typographically and metaphorically, the cover of his memoir tells the reader as much with “hanif kureishi. shattered. a memoir” highlighted in a found poetry of realization. However, what is also made clear, not only by the memoir’s cover, but by Kureishi’s enclosed “dispatches,” is that his self-expression through writing has not been shattered.

It’s fair to say that after a fall on Boxing Day while in Rome, Hanif Kureishi felt his life and the lives of those around him had been shattered. Both typographically and metaphorically, the cover of his memoir tells the reader as much with “hanif kureishi. shattered. a memoir” highlighted in a found poetry of realization. However, what is also made clear, not only by the memoir’s cover, but by Kureishi’s enclosed “dispatches,” is that his self-expression through writing has not been shattered.

Shattered: A Memoir (Ecco; February 2025) starts with Kureishi recounting the accident that changed his life. Feeling ill while watching television, Kureishi fell forward and awoke in a pool of blood with his neck twisted. As a result, Kureishi lost the use of his arms and legs. The memoir, recounting both the event and his recovery that follows, is dictated to his partner, Isabella, and his three sons.

Within the first few pages of Shattered, writing and collaboration emerge as a haven of creativity for Kureishi and his family to process his accident, heal emotional and physical distress, and evaluate their altered futures. He writes, “This writing I have done in hospital, dictated to Carlo and my family, has sustained me. I want to keep going (267).”

With writing as a constant part of his identity, especially in the thick of trauma, Kureishi leans into his writerly identity. He muses:

I am aware of this in my own life; as a teenager I was so traumatized by racism and the unpleasantness of school that I began to read and write at a remarkable rate. You could say that trauma saved me and made me into a writer. Something similar is happening here: I am finding a way to cope with the shock of my recent accident by writing through dictation (68).

As Kureishi finds his other identifying factors changing such as his swift reckoning with his identity as able-bodied becoming disabled, writing is the only constant and relationship that remains relatively unchanged. Although now, he must dictate his work, Kureishi confronts trauma to retrieve the salvageable lessons, emotions, stories, and relationships he can use to cope and fuel his writing.

Writing, ideas, and the way his mind works, are the faculties he can hold onto. Kureishi stares directly at the unpleasantness of trauma and dictates all of it as a means to cope. He doesn’t stray away from the helplessness and loneliness he feels, the death of a fellow patient he befriends, and the various medical procedures he undergoes. The constant and valuable faculty of writing echoes throughout Shattered.

Kureishi tells the reader, “I’d like to add that I really enjoy writing these dispatches from my bed. At least I haven’t lost the one thing that was the most valuable to me, which is my ability to express myself (37).”

In the ability to express himself, Kureishi finds the beauty of collaboration. Kureishi is forced to confront the fact that he is no longer as independent as he was in the past and must rely on others for everyday tasks. His life is now a collaboration and partnership more than ever between his partner, his sons, his friends, his doctors, his nurses, and his fellow patients. With the idea of partnership in mind, he also challenges the idea of the lone writer.

While discussing The Beatles, he wonders if the public would have ever heard of Lennon and McCarthy without each other? He goes on to state,

This is both a miracle and a terrible dependency. In my experience, all artists are collaborationists. If you are not collaborating with a particular individual, you are collaborating with the history of the medium, and you’re also collaborating with the time, politics and culture within which you exist. There are no individuals (15-16).

It sparks his own revelations about writing, revising, editing, and expanding the dispatches with his son, Carlo. Writing as a collaborative act becomes a sort of freedom for Kureishi. He collaborates with not only his son but with genre, form, subject matter, and other cultural/political topics. Collaboration in writing opens the door for his acceptance of collaboration in other areas of his life, where his accident has made collaboration a necessity.

In these changed and modified relationships, Kureishi’s relationship to writing as a craft, his original identity as a writer, his collaboration with other writers and the medium remains unchanged. Writing is a static and familiar stronghold in his life, his longest collaboration, because as Kureishi knows far too well, “Writers nurse the human soul through its difficult journey in this impossible life (158).”

Sara Pisak earned an MA and MFA in nonfiction from Wilkes University. She is currently associate editor at The Disruptive Quarterly and a staff reviewer at Glass Poetry Press. Sara participates in the Poetry in Transit Program, and she has recently published work in Door = Jar, Whale Road Review, the Deaf Poets Society, Five:2:One Magazine, Moonchild Magazine, Yes Poetry, and Boston Accent.

Sara Pisak earned an MA and MFA in nonfiction from Wilkes University. She is currently associate editor at The Disruptive Quarterly and a staff reviewer at Glass Poetry Press. Sara participates in the Poetry in Transit Program, and she has recently published work in Door = Jar, Whale Road Review, the Deaf Poets Society, Five:2:One Magazine, Moonchild Magazine, Yes Poetry, and Boston Accent.