Reviewed by Dorothy Rice

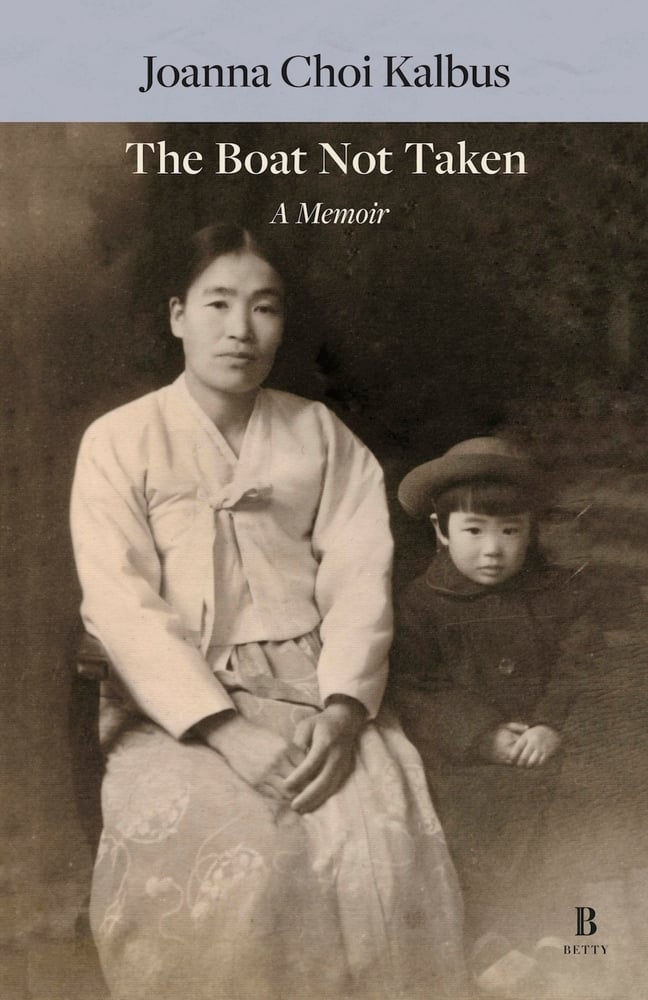

The Boat Not Taken: A North Korean Daughter and Her Mother’s Story (Betty; May 2025) by Joanna Choi Kalbus is one of the first titles from WTAW Press’ (a 501(c)(3) nonprofit) new imprint, Betty, established by director and editor-in-chief Peg Alford Pursell specifically for books by women, with the goal of showcasing the diversity of women’s voices.

The Boat Not Taken: A North Korean Daughter and Her Mother’s Story (Betty; May 2025) by Joanna Choi Kalbus is one of the first titles from WTAW Press’ (a 501(c)(3) nonprofit) new imprint, Betty, established by director and editor-in-chief Peg Alford Pursell specifically for books by women, with the goal of showcasing the diversity of women’s voices.

Choi Kalbus’ memoir is a particularly apt choice for the fledgling imprint; in her March 2024 Hippocampus Magazine interview, Pursell explained, “I named Betty after my mother, who was a prolific reader.” I say apt, and beautifully so, because The Boat Not Taken is the story of a mother and daughter, bound in a tight embrace by their traumatic, often painful, shared past—the loss of home, family, and community, escaping North Korea following the Communist takeover, then leaving South Korea for the United States when the narrator was a young girl.

In the introduction, Choi Kalbus first touches a theme that echoes throughout—the gauzy, patchwork nature of memory and the ways in which we are all, at times, unreliable narrators of our own past. She began writing about her mother, “my life’s historian,” in the aftermath of her death in 1996.

Choi writes, “Only then did I realize how much of my life was a sort of folktale. Only then did I realize how little I knew about her life and therefore my own. I began to understand something was missing from the picture I had formed of our life together.” From this realization—one that many who have lost loved ones have likely experienced—the author began a journey to discover the truth of her mother’s life, and by extension her own.

Choi Kalbus’ narrative brought me back to the myriad questions I never thought to ask my father before his death in 2011; like the author and her mother, he emigrated from the Philippines in the 1930s via freighter, with his older sister and Chinese mother. And, like the author’s mother, my grandmother spoke no English, was born into gentility and had never worked “jobs” to support a family; she arrived in San Francisco with no husband and two half white children. Now that it’s too late, I wish I had listened more and asked more questions, about their lives as immigrants, outsiders; like the author, my father’s sister, my Aunt Ruth—older and more outgoing than my father—likely served as translator, intermediary and cultural ambassador for their mother. I can imagine what their family of three may have experienced, yet I will never know—their stories are piecemeal, fragments with huge chunks missing.

In The Boat Not Taken, the author deftly, honestly, and vividly pieces together the known facts of her widowed mother’s life, inserting what she discovers through research and family interviews, and, along the way, dissecting and examining her own memories—the recollections and mental snap shots captured with a child’s perspective and limited understanding of the experiences and world her mother was forced to navigate. The author reflects, “Are these memories mixed with imagination and marinated in stories told over the years. My earliest recollections of my life in North Korea resemble a well-worn album of faded photos composed in a sporadic style.”

While it is clear that this devoted mother does all in her power to care for and protect her daughter, as refugees, their life after fleeing North Korea is one of poverty, privation, risk, and danger for a single woman—without the protection of a husband and his family, in a culture and time where women are defined and seen in terms of their relationships.

When the narrator is five, her mother is unable to care for her. She is left at an orphanage. Memories of this lonely, frightening time are acute and vividly brought to life. “In the darkness, I heard a girl singing and the big girl next to me breathing through her nose. I held my soft bundle to my chest and lay on my left side, the same position I had slept in with my mother. I hadn’t suckled her breast for a year now but we still slept with her right arm underneath my head, which faced her right breast, and my right hand pressed on her other breast. I clutched the bag tighter.”

The narrator had two brothers, though their experience after fleeing North Korea was vastly different from hers. Male children were more highly valued than girls. A younger brother was placed with relatives, the older brother was away at school, while mother and daughter subsisted on their own, sleeping in refugee camps and shacks, sharing a single serving of rice a day, working multiple demeaning jobs. The younger brother predeceased his mother.

Like most compelling memoirs, and many novels, the narrator is on a journey of outer and inner discovery, the reader carried along through insights, surprises and discoveries. I won’t provide any spoilers here.

On a trip to Korea to burn her mother’s clothes in her homeland (a Confucian ritual), the narrator hopes to reconnect with her older brother and to find answers to the long-standing, hurtful and confusing estrangement between mother and son, brother and sister. This aloof, accomplished older brother proves a perfect tour guide, professional and cordial; yet he invites no intimacies. Celebrating his birthday at a karaoke bar, the brother sings a familiar song, “. . . one my mother used to sing, a song in an atonal scale with a melody that was so sad, so haunting . . . “

“He sang the last stanza, sustaining the final note. So many birthdays our mother had, and had this son remembered even one? Not one card. Not one telephone call. She had kept all the cards she received in her lifetime. Only one postcard from her firstborn son. It appeared to have been sent from Washington, D.C., showing cherry blossoms in full bloom. There was no address or postmark, so it must have been enclosed in an envelope.”

The Boat Not Taken is the story of one woman who left Korea with a young daughter, two arrivals in a new world. Yet Choi Kalbus’ loving tribute to her mother, her Omai, is much more than that; it is a story of immigrant grit and fortitude, of a mother’s life in service of the next generation, her lifeblood spent uplifting her children and grandchildren. Like millions of others who have sought new lives by emigrating to this country—often driven by desperation, fear and necessity—the family and community, the land they left behind, is no longer a place that can be returned to; it doesn’t exist in the ways that once made it home. This sense of having severed deep roots and finding the soil in a new land at times unyielding and unwelcoming, is, I sense, true for many immigrants, in generations past, and today.

The United States is and has long been—since the arrival of the first missionaries and conquering Europeans—a nation of immigrants; preserving, honoring, never forgetting the stories of these American lives, is vital to understanding and appreciating who we are as a nation and to embracing our fundamental diversity.

Dorothy Rowena Rice is a writer, free-lance editor, Managing Editor of the nonfiction and arts journal Under the Gum Tree and a Board Member with the Sacramento area youth literacy nonprofit, 916 Ink. Her published books are The Reluctant Artist (Shanti Arts, 2015) and Gray Is the New Black (Otis Books, 2019). She is the editor of the anthology TWENTY TWENTY: 43 stories from a year like no other (2021, A Stories on Stage Sacramento Anthology). At age sixty, after retiring from a thirty-five-year career in environmental protection and raising five children, Dorothy earned an MFA in Creative Writing, from UC Riverside, Palm Desert. Learn more and find links to many of her published stories, essays, reviews and interviews at www.dorothyriceauthor.com

Dorothy Rowena Rice is a writer, free-lance editor, Managing Editor of the nonfiction and arts journal Under the Gum Tree and a Board Member with the Sacramento area youth literacy nonprofit, 916 Ink. Her published books are The Reluctant Artist (Shanti Arts, 2015) and Gray Is the New Black (Otis Books, 2019). She is the editor of the anthology TWENTY TWENTY: 43 stories from a year like no other (2021, A Stories on Stage Sacramento Anthology). At age sixty, after retiring from a thirty-five-year career in environmental protection and raising five children, Dorothy earned an MFA in Creative Writing, from UC Riverside, Palm Desert. Learn more and find links to many of her published stories, essays, reviews and interviews at www.dorothyriceauthor.com