Reviewed by Brian Watson

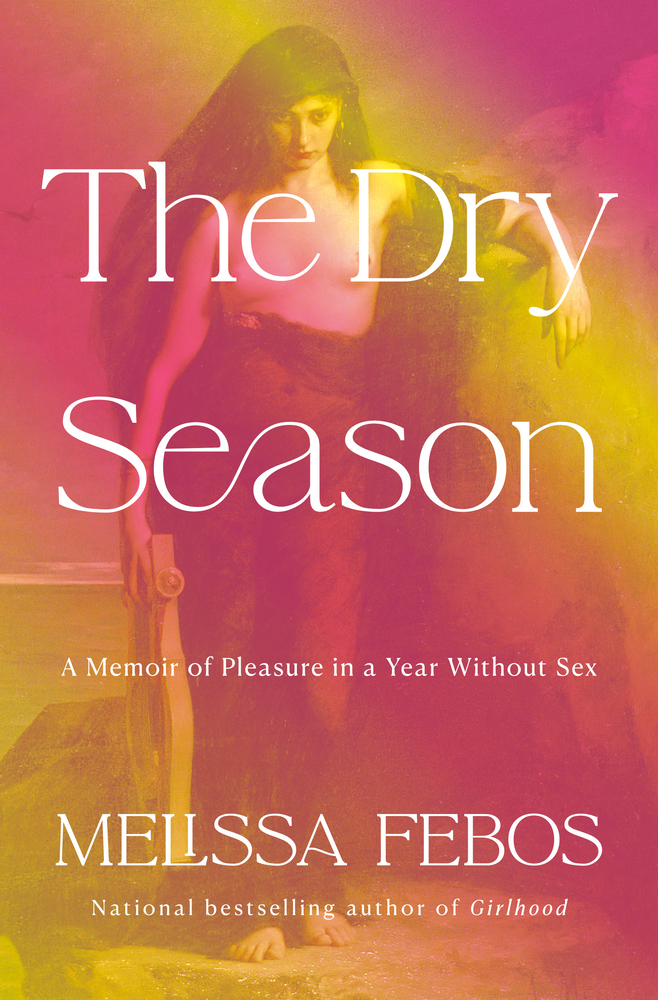

Melissa Febos’ The Dry Season: A Memoir of Pleasure in a Year Without Sex seems to demand two different reviews. One for readers of memoirs and one for writers of memoirs. For the readers, let me begin here.

Melissa Febos’ The Dry Season: A Memoir of Pleasure in a Year Without Sex seems to demand two different reviews. One for readers of memoirs and one for writers of memoirs. For the readers, let me begin here.

I fell in love at the first sentence: “It is raining.” Three words, and yet evocative of the wide range of emotions that rain can trigger. A few more pages, and Ms. Febos has a direct cue for the reader: “As in love among humans, we cannot appreciate a text until we really see it, and in order to see it we have to get out of the way.” This encapsulates the journey the reader then shares with the author. To see, to know love, we have to get out of the way.

As a reader charged with reviewing this incredible memoir, I made an uncommon mistake: I inadvertently glanced at someone else’s review. The Seattle Stranger, my local independent newspaper, included this, to my mind, odd phrase: “…[Febos’] bare zero-percent flowery confessions….” As a fan of Ms. Febos’ writing for many years, I didn’t understand how the word “flowery” crept in there. It’s mildly misogynistic; the implication being that women are expected to be excessively adjectival in their writing.

The writing in The Dry Season is smart and funny, and it blooms on the page like acres of flowers: “In the lesbian Olympic games, peacefully assembling IKEA furniture with missing screws on a team with your ex would be an advanced category, and we would have medaled.”

Equally floral, naturally beautiful, is the memoir’s topic. Several years ago, Ms. Febos realized that she had never not been in a relationship, segueing from partner to partner since her teen years. Those relationships crescendoed in pain, however, leading to one relationship in particular that she describes as a Maelstrom. That pain, those relationships, and their accreting traumas, force a grudging realization: it might be time for a break, to experiment with celibacy.

Her initial plan called for three months, but she documents the challenge of that effort from the outset. Early on, she writes:

“It was always a question of how honest I wanted to be with myself. Did I really want to change, to live according to my own beliefs? Or did I secretly prefer to go on as I had been. I mean, why bother with such a project if I wasn’t going to be wholehearted? The prospect of giving up all the pleasures of romance seemed downright sepulchral. But why was I actually doing this? Was it solely to avoid another maelstrom? To relieve my depression? I had already accomplished the latter, but knew I wasn’t finished. The point of my celibacy wasn’t merely to take a break, but to make room for change. I’d barely begun.”

It is this self-examination that creates the most light within The Dry Season. As Febos documents her expanding commitment to a longer period of celibacy, she takes inspiration from twelve-step programs and embarks on an inventory of her past relationships. And because she is hoping that inventory will enlarge her understanding of the flaws within those relationships, the patterns in her behavior, she shuns her attempts to filter her recollections, to offer explanations, justifications, excuses as she writes.

“Sometimes, I thought, I am in love. Every time, there was a kernel of knowing inside me. A bud of nascent certainty that it would end, that I would be the one to end it. The why, even, layered in its fragrant darkness.” Let me remark once more how her words blossom on the page—fragrant darkness.

The inventory is not, however, an attempt at self-pity. “The beauty of the inventory was that its aim was to locate not blame but my own responsibility, to let those stories settle in the in-between space where all love ultimately lay: the field on which every person did their best, whatever the wreckage.” This is such a generous and, yes, loving, perspective to hold to. I can imagine many readers, myself included, now inspired to consider their relationship histories with perhaps more than a modicum of kindness. How many of us cling to guilt over failed connections, abandoned lovers? How many of us need that internal embrace? I did my best, whatever the wreckage.

As Febos’ journey continues, her self-understanding deepens. When she ultimately shares her inventory with a person she refers to as a spiritual advisor, the conclusion the advisor reaches is that Febos is manipulative, a user. Febos pushes back at first, saying that she sees herself as a people-pleaser, but the advisor immediately corrects her. People pleasing is people using.

The reader might well catch on to this aspect of Febos. Earlier in the book, we read: “…what I wanted from [my partners] was ultimately more subtle than that: to secure their focus, to make them like me. To cast a bit of glamour, a spell of protection. When I caught the flapping sail of their attention, I felt a swell of safety and power. For a moment, I soared. I wanted redemption, too, probably. That liquid pleasure without the risk. For that, I needed to be the one at the helm.” A user, indeed.

But the author is not only chronicling her relationship history, a soul-bearing exercise few writers might take on. This writer, for example, still worries how their mother will react when their memoir is out in the world. What makes The Dry Season truly glorious, above and beyond the efflorescence of Febos’ writing—flowery in all the best ways—is how the text charts a path forward for its readers. Febos not only broke free from her Maelstrom, but she demonstrated how she sought change, change that led her away from her history of manipulation and that guided her to a whole and open heart.

“My past partners were not responsible [for how my past relationships played out]. It was my dependence upon managing them, upon the belief that I must. For the addict, a single day is the only unit of freedom. Before my celibate period, I had not gone a day in twenty years without entertaining the ways I did or should or would or could appeal to other people and conform to their desires. My attempt to replace dependence with independence and interdependence… was the radical basis of all feminisms. It was the basis of all freedoms.”

Let me now turn to my memoir-writing siblings.

The Dry Season is a masterclass in the authoring of memoirs that are both lyric—less concerned with chronology than with the import, the meaning of things—and researched. In her journey to and through celibacy, Febos draws inspiration from feminist pasts. She introduces us to the beguines, the “gray women” of the early Middle Ages who insisted on not only exploring their spirituality but in documenting it, things that few women of that era would have been permitted to do. She reminds us of Sappho’s poetry, of Saint Augustine’s laments, and of the oddness of courtly love as epitomized by Medieval troubadours. Her more recent inspirations are myriad as well. Nan Goldin, Helen Gurley Brown, Audre Lorde, Roland Barthes, Michel Foucault, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Virginia Woolf, bell hooks, Susan Sontag, and John Waters.

Febos weaves her research effortlessly into her narrative, a process I witnessed up close during her Story Studio Chicago lecture on researched memoirs last summer. Paragraphs effortlessly elide from personal narrative to historical context, enriching her text in ways that engage the reader without veering into the lifelessness some know from academic writing. All Febos writes about is in service to her narrative, in service to the personal growth each page of The Dry Season bears witness to.

As a writer, I took particular solace in these sentences: “The writer of a memoir is both the director and a character in her play, and thus enjoys refuge outside of its narrative. An author is the god of their story and must sustain the long view, the cool curatorial eye. I wanted my art to be beautiful, even when it described something ugly.”

Writers and readers alike will adore The Dry Season. It is Febos’ best memoir to date and deserves every accolade.

Brian Watson’s essays on queerness and Japan have been published in The Audacity’s Emerging Writer series and TriQuarterly, among other places. An excerpt from CRYING IN A FOREIGN LANGUAGE, their memoir’s manuscript, was recently accepted by Stone Canoe for the September 2025 issue. They were named a finalist in the 2024 Iron Horse Literary Review long-form essay contest and won an honorable mention in the 2024 Writer’s Digest Annual Writing Competition. They share OUT OF JAPAN, their Substack newsletter, with more than 600 subscribers. In 2011, their published translation of a Japanese short story, MIDNIGHT ENCOUNTERS, by Tei’ichi Hirai, was nominated for a Science Fiction and Translation Fantasy Award.

Brian Watson’s essays on queerness and Japan have been published in The Audacity’s Emerging Writer series and TriQuarterly, among other places. An excerpt from CRYING IN A FOREIGN LANGUAGE, their memoir’s manuscript, was recently accepted by Stone Canoe for the September 2025 issue. They were named a finalist in the 2024 Iron Horse Literary Review long-form essay contest and won an honorable mention in the 2024 Writer’s Digest Annual Writing Competition. They share OUT OF JAPAN, their Substack newsletter, with more than 600 subscribers. In 2011, their published translation of a Japanese short story, MIDNIGHT ENCOUNTERS, by Tei’ichi Hirai, was nominated for a Science Fiction and Translation Fantasy Award.