Interviewed by Diane Gottlieb

There is no shortage today of books written about the Holocaust. But when Julie Brill searched for one specifically about the Holocaust in WWII Serbia, she came up empty.

Brill’s dad was born in Belgrade in 1938. He had been sharing stories of his childhood with her since she was a young girl, yet none of the books she read growing up reflected her dad’s experience. A lover of history, Brill wanted to find out why. She also wanted to learn how: how had her dad survived when 90% of the Jewish population in Belgrade had been murdered by the Nazis? It wasn’t until many years later, when her daughters left for college, that Brill began a search in earnest.

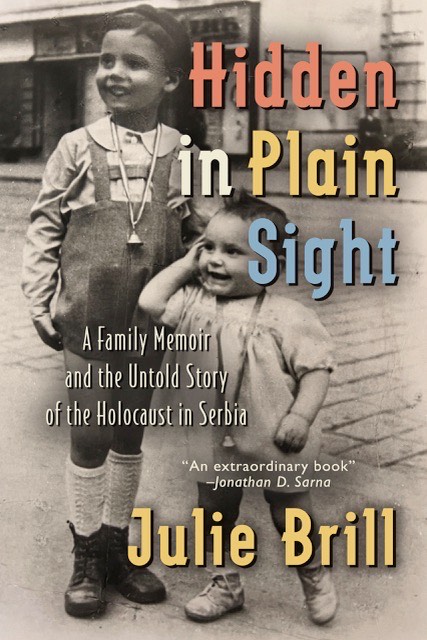

Hidden in Plain Sight: A Family Memoir and the Untold Story of the Holocaust in Serbia (Amsterdam Publishers; April 2025) tells the story of that search and of the largely unknown and tragic history of Jews in WWII Serbia. Through the eyes of a daughter eager to learn more about her father’s younger years, readers are treated to both literal and figurative journeys. After Brill learns the family secret that answers the “how” of her dad’s survival, she and her father travel to his homeland. They not only deepen their bond on the trip, but it is in Belgrade that Brill connects with the part of her identity that had been kept from her for so long.

I had the great pleasure of speaking with Julie Brill over zoom about the journeys, her meticulous research, and the surprises she encountered along the way.

Diane Gottlieb: Congratulations on a wonderful memoir, Julie! Let’s begin with your childhood. While many Jewish children have an interest in learning about the Holocaust, that interest often runs especially deep for children of survivors. Can you share how yours developed?

Julie Brill: My first exposure to the Holocaust was my father’s stories of his life in Serbia during World War II, although we didn’t label them “Holocaust stories” at the time. I learned little bits of his childhood memories without any historical context. My dad didn’t really have the historical context either because he was only ten years old when he left the country.

I went to Hebrew school in the early ’80s, where we learned a version of the Holocaust that focused on Germany and Poland. I had trouble equating what happened there with my dad’s experiences. I couldn’t find any library books on the Holocaust in Yugoslavia and of course, there was no internet. I read every book on the Holocaust I could find but couldn’t couple my dad’s recollections in Belgrade with the history I was reading. It’s only recently that I’ve been able to figure out how the stories all fit together.

DG: A lot of survivors didn’t talk about their experiences, but your dad made it a point to tell you. What kinds of things would he share?

JB: He would tell us the same little vignettes—child-sized memories—over and over. One of those memories was about how much he liked chocolate. Chocolate was rationed at the time. He would ask his mother not to put chocolate in his birthday cake but to save it instead. Another memory he recalled was the sound of bombs and running to the shelter. A plate that my grandmother had put on a shelf had broken in two. He was fascinated by the fact that the plate hadn’t shattered.

His memories were all mixed together—stories of the Holocaust and the War, but also stories of moving to Israel when he was ten and others that aren’t related to the larger situation, like living on a farm and fishing in a brook. I would ask him questions. I would ask my mother questions. I was fascinated by historical events, about what life was like during different times in history. My dad and I were a good match: he wanted to tell the stories and I wanted to listen.

DG: How was your father’s story different, and how did you deal with the disconnect?

JB: I was taught—and read about—only two types of Holocaust stories: a hidden child story like Anne Frank’s and the stories of the trains and the camps. My father’s was different. My grandfather was in a camp, but my grandmother walked to the camp where he was held and brought him food. How did that happen? That’s not how it works in other stories, but it was how it worked in Belgrade. Those stories that we learn mostly represent the survivor Holocaust experience. More Jews were murdered outside the camps than in them. But we don’t hear many of those stories because we don’t have survivors to tell them. I was always trying to piece the inconsistencies together.

DG: This mission of “piecing the inconsistencies together” started in earnest when your own daughters left the nest. Tell us the steps involved.

JB: I started researching in 2017 when my younger daughter went to college. I got in touch with the Jewish Museum in Belgrade, Serbia, part of the former Yugoslavia, without any expectation, yet I received an email with a hundred years of documents —Brill documents—that led up to the Holocaust.

The documents made me feel like this is researchable, that the information does exist, and I might be able to find it, so I kept going.

DG: Along the way, you learned of a family secret. What was that secret?

JB: In the 1930s, my grandmother converted from Catholicism to Judaism in order to marry my grandfather.

DG: You discovered this information from a document and had no idea that your dad already knew. Your mom didn’t think you should tell him. He had kept the information of his mother’s conversion from your mother as well.

JB: She had no idea. My dad had immigrated with his mother and sister in 1948 from Yugoslavia to Israel. In 1964, he came to Boston, where my mother met him. To her, he was Israeli, and so she just assumed he was Jewish. He is Jewish, but she never questioned his family lines.

DG: Your mother ended up telling him.

JB: She did. Now we talk about it as if it never was a secret. It was something that I had suspected. It was actually a question I asked while requesting the documentation from the museum. Could this be possible? Were people converting to marry in Yugoslavia in the 1930s?

DG: What was finding out about your grandmother’s conversion like for you?

JB: Mostly a big relief. It felt good to know the truth, to have things make sense. Also, it gave me more of a connection to Belgrade. I was raised with this feeling like, “You’re Jewish, we’re from all over, but we’re not really from anywhere.” Now I was from a specific place and an ethnicity and a culture. It was fun finding new connections.

DG: Learning about your roots changed how you saw your identity.

JB: Very much so. When we went to Belgrade, I thought “we look like these people. We fit into this place. They understand the story that we’re telling.” The fact that our story made sense to them was really powerful.

DG: You went to Belgrade with your dad. Why did you decide to make that trip?

JB: I thought it would make things more real and relatable. Belgrade was where my dad was from, where these stories took place. But it had always been a place we couldn’t go. There was the Cold War. Time and money and the Balkan Wars. Finally, it just seemed like, “This is the moment we could go.” It was this perfect intersection. My dad was still young and healthy enough to go. He wanted to go. We had the internet, so we had all this information. My kids were grown. My dad was like, “The barriers are gone. Let’s just do it.”

DG: Many people take these kinds of information-seeking trips when their parents have already died. How wonderful that you were able to go with your dad.

JB: I’m really lucky to have been able to do that. I was hoping, and it came to pass, that there would be new memories. Standing in the places where things happened brought out more stories.

DG: Were you nervous about how your dad would react to being back in Belgrade?

JB: Of course. He volunteered to come along, but it wasn’t his idea. The past is complicated in many ways. He has happy memories there. He has terrible memories there. I didn’t know what the experience would be like, what people might say to us, or how the Holocaust would be viewed by Serbians on the street.

DG: Your daughter joined you and your dad. It was a three-generational trip.

JB: That felt even more like passing it down. She now has memories of hearing him tell his stories in the places where they happened. There will hopefully be generations after that who will hear the stories from her.

DG: One of the differences between your father’s story and the ones more widely accessible is that in Serbia, there were no gas chambers. They gassed people in vans.

JB: The war came early to Serbia. Gas chambers weren’t yet up and running anywhere. Gassing people in vans was a precursor to that.

DG: You wrote that the German soldiers didn’t like shooting women and children, so the military came up with this solution to save the soldiers from having to pull the trigger.

JB: If you take it from a civilian point of view, the occupied population, the military was bringing the gas chambers to them. Because the vans only worked when they were moving, the killing took place while the vans were literally being driven down the streets of the old city.

It’s a different story than the one we usually learn.

DG: Do you feel you’re really telling a very important story here because people don’t know about it?

JB: That’s exactly why I wrote the book. If somebody else wrote a book about the Holocaust in Serbia in English, I would have put the pen down. I felt like someone should do this and there’s no one else, so I’m the someone.

DG: Has your relationship with your dad changed after taking the trip and after writing the book?

JB: We definitely got closer in this process. Traveling together, sharing this information, figuring out this puzzle. I feel like I was giving something back to my dad that was stolen from him. That was satisfying for both of us.

DG: One of the reasons your dad survived was that he and his mother went to live with his grandmother, who was Catholic. The fact of his Jewishness had to be kept secret. He was instructed never to pee in public, as his circumcision would give away his Jewishness. His grandmother lived on a farm. Even though it was removed from the city, it was not removed from danger.

JB: My dad lived on a horse farm where German soldiers would rent the horses to ride on their days off. He would watch them. His grandmother cooperated with partisans. She allowed them to use the barn for storage. They would leave weapons in the spaces between the horse stalls. The soldiers came during the day. The partisans came at night.

DG: Your great-grandmother must have felt constant tension. The stakes of helping the partisans and of hiding her Jewish daughter and grandchildren were so high, but it seems she and your grandmother were able to shield your dad from those same tense feelings.

JB: They somehow were able to give him a false sense of safety. He felt confident they were keeping him safe, which they luckily were able to do.

DG: Tell us about Stumbling Stones.

JB: Stumbling Stones—or the Stolpersteine, as they’re called—are about the size of your palm, and they’re installed on the sidewalk in front of the last voluntary residence of Holocaust victims and survivors, just slightly higher than street level. The person’s name, their birthday, the date they died—and where—if there is access to that information are on the stone. When we stood outside my family’s former home in Belgrade, I wanted some sign that my grandfather had lived there and that there once was a Jewish community there, too.

I didn’t understand that the fact there weren’t any markers was a deliberate choice. Full of American optimism, I thought, I’ll just make it happen. It wasn’t as simple as that, but I partnered with an NGO called Haver Serbia, and we were able to get the first ten stones in Belgrade, including one for my grandfather.

My father lived with my grandparents and two uncles, but only my grandfather has a stone. They should all have stones, so that’s the next project. So far, we’ve not been able to get that done.

DG: When that comes to pass, do you think you will be finished with this project?

JB: One of the things we found was a document of Germans checking off Jews reporting for slave labor. My grandfather’s name is on that list with a pencil check. You see other people on the list with no check next to their names.

I had a feeling that there were no survivors coming back to look for them. I started researching and came up with dead ends. Did they not show up because they were dead? Had they escaped? I was tracking other Brills who were probably related, but I couldn’t draw the tree.

There’s always more to trace and try to find out. I feel like I’m still living the story and making new and some wonderful discoveries. I’ve been able to connect with so many people because of the book. I had someone come to my book launch and discovered we’re probably cousins. People with family from Serbia reach out to me. They also thought, “I have this story that happened to no one else.” That has been a part of this journey I didn’t expect—that the writing of the book would lead to more stories. It’s ongoing. I don’t think it will ever be complete.

Diane Gottlieb received an MFA from Antioch University Los Angeles where she served as lead editor of creative nonfiction and as a member of the interview and blog teams for Lunch Ticket. Her work has appeared in the Brevity Blog, Entropy, Burningworld Literary Journal, Panoply, and Lunch Ticket. You can also find her weekly musings at her website.

Diane Gottlieb received an MFA from Antioch University Los Angeles where she served as lead editor of creative nonfiction and as a member of the interview and blog teams for Lunch Ticket. Her work has appeared in the Brevity Blog, Entropy, Burningworld Literary Journal, Panoply, and Lunch Ticket. You can also find her weekly musings at her website.