Interviewed by Amy Goldmacher

If you’re lucky, your writerly sensemaking activities mean you encounter other writers traveling similar paths. This was my experience taking a class from Melissa Fraterrigo on developing memoir essays in the summer of 2024.

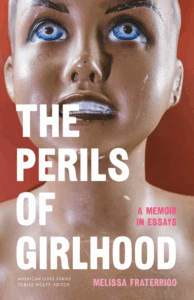

A skillful teacher, Melissa helped a small group of writers refine and polish essay drafts. We found interesting commonalities between our work. When I had questions about places to submit my experimental memoir, Melissa had insight for me based on her experience finding a home for her memoir-in-essays, which questions how growing up in the 1980s and 1990s shaped us as mothers of the next generation of women. The Perils of Girlhood: A Memoir in Essays, now available for pre-order, provided me with the excellent opportunity to once again learn more from her.

Amy Goldmacher: What was your process for writing The Perils of Girlhood, and how did you go from “I have an idea for a book” to this book, coming out in September 2025?

Melissa Fraterrigo: My first two books were fiction, and I spent four years writing a young adult novel that I was pitching during COVID. Long story short, I could not find a home for it. And somewhere in the process of searching for a home for that novel, I became a little more reflective and found myself drawn to memoir essays. I began writing about my childhood and adolescence and adulthood, and really found myself curious about not only what happened at that time, but my response to that in the present.

But it wasn’t until my twin daughters began to encounter in real life some of the issues that I had grappled with decades ago — struggles with body image, disordered eating, the legacy of insecurity — that I wondered how I might help them navigate their own experiences with girlhood.

AG: Why essays? What was that process of figuring out essays as the medium that you wanted to communicate in?

MF: I love the essay form. I love the spaces that exist between essays. There’s breathing room that invites the reader in a way that’s unique from other modes. I like the messiness of letting myself figure some things out on the page. The inherent leaps and retrospective reflection that is inherently a part of Vivian Gornick’s situation and story. The fact that The Perils of Girlhood didn’t evolve in the way that I originally conceived of it is actually a strength because it has developed into something on its own. It’s something that is a little bit more organic than just sticking to that initial plan, you know?

AG: So many writers, myself included, want to figure everything out ahead of time, but that’s not how it works, unfortunately.

MF: Did you do that with your own book?

AG: No, the final form was definitely something that emerged over time.

MF: I think that that’s really fascinating. I love that word that you used, emerge. A word, a memory, a sound or image — something takes root subconsciously. Letting the creative process really drive us or the project can be unsettling, and yet it can also be thrilling.

AG: Do you have any advice for writers to sort of turn on the messy creative process, to allow the “see what happens” part of the process?

MF: I have a lot of advice! I love journaling. I find it centering and do my own version of Julia Cameron’s Morning Pages nearly every day. Read work that you admire and hope to emulate. If I find myself having a difficult time, I lower my expectations, and write something that may not turn into anything. We have to have our radar turned toward joy. We have to ask ourselves, what moves me now, in this moment?

Annie Lamott talks about the 1-inch window. What can I see just in this little square? Whether I am walking my dog or chopping carrots, I can be aware of what I’m noticing. I can tap into how the wind feels on my face and how this connects to the backyard swing from my childhood. I can be aware of the sound of the knife on the cutting board. If this were a piece of writing, what word might I use to describe that sound?

I remember when I knew I had a complete draft, but the manuscript still wasn’t where it needed to be, I was casting about for additional feedback and I asked a woman from a writing group to read the manuscript. She came back with some pretty drastic suggestions and I was devastated for a couple days and then I kind of had to pick myself up and dust myself off and realized that those suggestions weren’t helpful to me and that was okay, that that wasn’t what I was doing. I had to start to trust myself and the little voice that said that what I was creating was worthwhile.

AG: Is there any overlap or continuity from your fiction book from 2017, Glory Days?

MF: Glory Days is a novel-in-stories. So, I think I have a kind of respect for a form where there is some space between chapters in that book and between essays in The Perils of Girlhood. In both books we leap between different situations and time periods with a keen attention to language.

AG: I know that it’s really important to you to talk about what it means to raise girls and to be a woman in this world.

MF: There is no period at the end of that sentence. This is something that’s still evolving. And when I’ve talked with other women about my experiences growing up female in the 1980s and 1990s with a swim coach’s advances, my father’s temper, and the undeniable joy of female friendship, they say “something similar happened to me.”

I think that in terms of raising girls now, we have to be mindful of where we’re coming from, and yet also realize that girls today will have their own traumas and delights. Maybe we can listen better; maybe we can offer additional opportunities for support. I remember trying to tell my mom about an assault that happened when I was in college and it was late at night, and I was home on spring break, and she so tired.

I don’t know that any parent knows how to listen to their child’s pain and heartache. But I’d like to think that my own daughters know that I’m always here to listen to whatever they want to tell me. And maybe in the process of us listening better, maybe it’ll be easier for them to tell us more.

AG: I think that’s really powerful. Maybe as generations move on, we keep getting better at listening and being able to hear beyond our own limitations. There might be skills that our parents didn’t have that we have and our children might have additional skills that we don’t have. And so we’re kind of pushing growth in that way.

MF: I agree! And yet I’m sure there’s lots of things I’m dropping the ball on as we speak. But that’s the power of the essay, that opportunity to go back and to reflect and hopefully do some deep thinking and meaning making about life.

AG: That’s all you can do. That’s all any of us can do.

Amy Goldmacher is a writer and a book coach. She is the winner of the 2022 AWP Kurt Brown Prize in Creative Nonfiction, and her experimental glossary-form memoir, Terms & Conditions, will be published by Stanchion Books in Fall 2026. She can be found on social media at @solidgoldmacher and at amygoldmacher.com.

Amy Goldmacher is a writer and a book coach. She is the winner of the 2022 AWP Kurt Brown Prize in Creative Nonfiction, and her experimental glossary-form memoir, Terms & Conditions, will be published by Stanchion Books in Fall 2026. She can be found on social media at @solidgoldmacher and at amygoldmacher.com.