Reviewed by Sandra Eliason

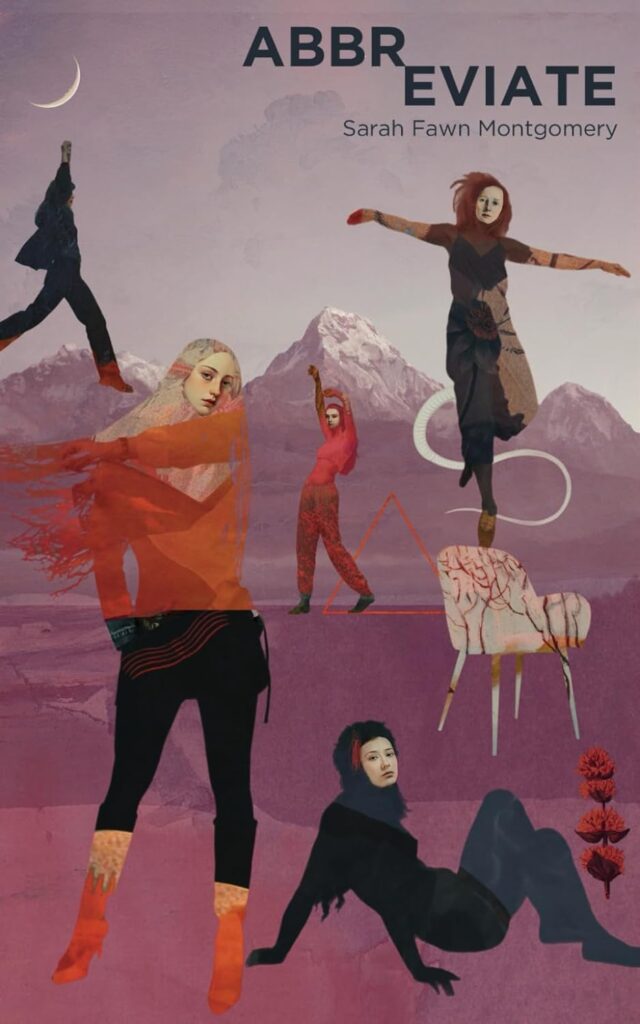

Sarah Fawn Montgomery has a way with words. In her memoir of mini-essays, Abbreviate (Harbor Editions; 2025), she uses them in unique and startling ways, both to create a scene and to set a mood.

Sarah Fawn Montgomery has a way with words. In her memoir of mini-essays, Abbreviate (Harbor Editions; 2025), she uses them in unique and startling ways, both to create a scene and to set a mood.

Her first chapter, “Stomp,” describes “the old railroad rattling through our town in search of something safer.” Something is unsettled here, which she will describe as the essay unfolds, alluding to the abuse her aunt experiences, and the danger surrounding them.

In each essay, phrases of beauty fill the page, such as in the opening of the second, “Planetarium,” which begins, “Overhead, our stories are as big as the sky.” And from the chapter, “Dash”:

At dusk the light goes diffuse, like slow motion,

like simple. The backyard trees are velvet; cirrus swift

brushstrokes make the sky seem safe. The railroad rattling

through the front yard slows too, whistle filtered through

the gloaming until it sounds like a dream.

But there’s something more than beauty going on with these words. They are carefully chosen to set a tone that can best be described as uneasy, perhaps melancholy, maybe a little bitter, which strike a chord in each chapter because each one finds a universal truth. Take this paragraph, for example:

No one comes to your sleepovers because last

week a bar fight left a man dead on Main Street. Because

the house by the riverbed pulses meth smoke like rotten

eggs. Because the rusted-out cars look like piles of bones.

Because your parents’ fights about money are so big and

loud that you hide beneath your bed.

We have not all had the experience of a man dead on main street or meth by the riverbed, but you can’t be a girl without having been left out, “othered” for your own differences.

The book is short at only seventy-four pages, but long on situations most women have found themselves in, delivered in a form that most resembles poetry.

We get small like how Tasha hasn’t eaten in a

Month…, throws up now before class… We get small

like how we disappear in math class, all the problems

about billiards and trains, imaginary men named Dave,

and in history, too, the textbooks absent of women…

You are praised for disappearing. For the way your

stomach collapses on itself, simply giving up, or the way

your ribs create a bowl around your hollowness.

… But no one wants you, just your not-a-body. You are only something

because you are nothing.

The gut-punching truth of this observation hit me in the reality of what it was like to be female. My husband and I went out to eat last weekend, and while I shared his salad, waiting for my main course, the woman sitting on the barstool next to me leaned over to say, “You are so good. I wish I could have so much restraint,” as though not eating had something to do with morality.

Women also understand what it means to hold in anger. Montgomery says in “Hug Your Mad,”

Mama says mad freezes your face, so little girls

with feelings be careful. Anger shows ugly over time, lines

between your brows or pulling down the corners of your

mouth. Girls should smile, say sorry. They should hug

their mad until it disappears.

The chapter goes on to describe all the reasons Montgomery has to be mad, and all the ways she tries to sublimate it or is made not to acknowledge it. As girls, we are taught to stuff our rage, smile, be polite, and let men lead, as she discusses in the final chapter, “Men teach Me How to Play Dungeons and Dragons,” which also displays the dissatisfaction men show when you don’t follow where they lead.

The book roughly follows memoir style, the first stories memories of childhood, and subsequent chapters relating truths from later periods in her life. In college, for example, she learns:

In literature, women are too untrustworthy to see beyond

their own pride to realize at first that they should marry the

wealthy man who is supposed to be swoonworthy, but mostly

seems boring…

In class, no one believes a woman who raises her hand,

uncertain, to answer a question, or who whispers

something to the teacher when called on unprompted.

“What makes you think so?” professors ask, teaching us

how to read closely but also that a woman’s opinion

should always bear the burden of proof…

In bars, no one believes a woman who says she is

not interested in a free drink, in a dance, a phone number,

a ride home… At home, no one believes a woman who says she

is frightened by the boys and men in her own family. .. ‘You’re overreacting,’ they say. ‘Don’t be so sensitive.’ Eventually, I believe them, believe

myself suspicious.

Her response?

I try to write literature where the woman is me, where I tell all the stories no one

has ever believed. There is the story of a woman who was

assaulted by a man over and over, though she never

reports it because who would believe that she didn’t

deserve it, who would believe that she was foolish enough

to allow it to happen, and more than once?

Here Montgomery taps into the universal response of fear of being believed, the syndrome of “It’s all in her head.”

Told from the perspective of one woman, this is the generic story of womanhood, gaslit until we almost believe it ourselves:

At home, alone, doubt is my favorite game… I wonder if truth is a star that eventually burns out. I wonder if a woman is a fact or a fiction. I

stand a long time in front of the stranger that is me in the

mirror trying to decide.

I could relate to the situations in all these stories. They create generalizable truths from the very specific. How often have I stood silently while a man who arrived after me was served first? Sat and listened while a man rephrased what I just said and got the response I didn’t. How often have we all been afraid simply because our body habitus was one gender not the other? How many times have we known it was not fair and stayed silent? Read this book for catharsis.

Sandra Eliason is a retired doctor who has turned to writing full-time. In 2016, she won the Minnesota Medicine Magazine Arts Edition writing contest. Since then she has taken multiple writing classes, gone to conferences, joined writers’ groups and worked to hone her craft.

Sandra Eliason is a retired doctor who has turned to writing full-time. In 2016, she won the Minnesota Medicine Magazine Arts Edition writing contest. Since then she has taken multiple writing classes, gone to conferences, joined writers’ groups and worked to hone her craft.

Sandra has been published in Bluestem magazine, the Brevity blog, been anthologized in the e-book Tales From Six Feet Apart, and has an upcoming piece in West Trade Review (April). She is querying her completed memoir, Heal Me—Becoming a Doctor for all the Wrong Reasons (and Finding Myself Anyway). You can find her in Minneapolis, Minnesota, where she lives with her husband. She has a garden in the summer and a cat to warm her lap in the winter. Look for her on Twitter @SandraHEliason1 or Instagram @sheliasonmd.