Reviewed by Anthony J. Mohr

Madeleine Pollard came from an everyday family in Kentucky, a girl who used her charms to worm her way into Washington, D.C.’s elite society. By age 17, she tumbled into an affair with William C.P. Breckinridge, a 44-year-old congressman from her home state. The liaison would last 10 years until he tossed her aside and married someone else.

Madeleine Pollard came from an everyday family in Kentucky, a girl who used her charms to worm her way into Washington, D.C.’s elite society. By age 17, she tumbled into an affair with William C.P. Breckinridge, a 44-year-old congressman from her home state. The liaison would last 10 years until he tossed her aside and married someone else.

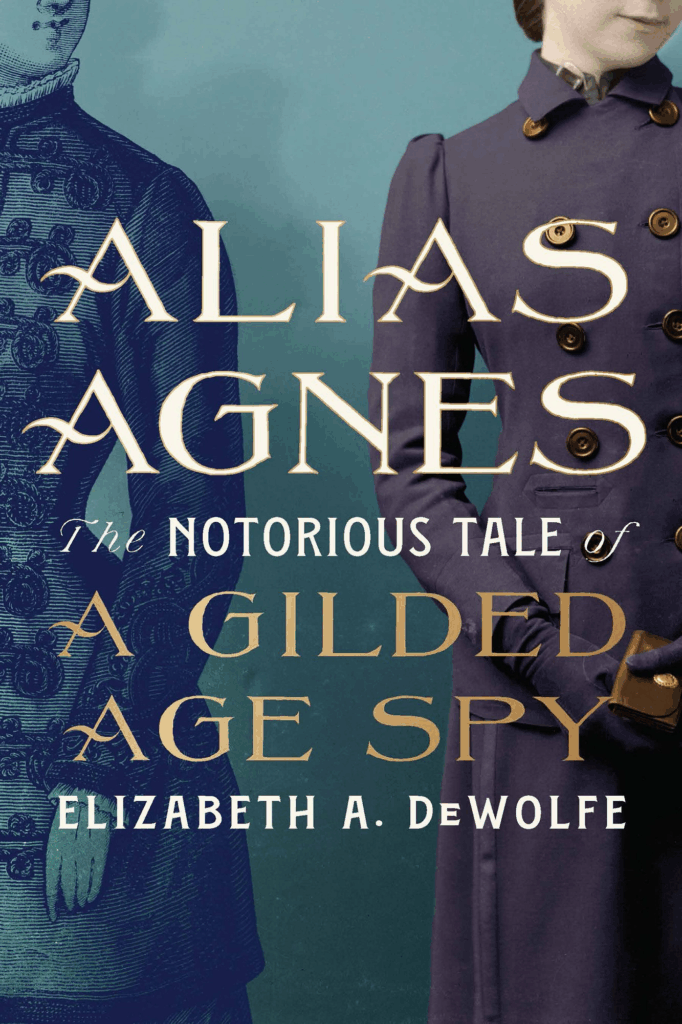

Pregnant at the time, Madeleine didn’t take that lying down. She sued for breach of promise to marry, a powerful cause of action during the 1890s, when the lawsuit took place, followed by a trial. In a well-paced narrative, Elizabeth A. DeWolfe shows what happened in Alias Agnes: The Notorious Tale of a Gilded Age Spy (The University Press of Kentucky; March, 2025)

As the author writes:

“The loss of Madeleine’s past and future was not mere romantic rhetoric. Breach of promise established that jilted women suffered injuries, depriving them of the financial security and the social and economic advantages a marriage brought. .. A woman’s security was her reputation, which was built on the notion of respectability.

For much of Victorian society, female respectability entailed chastity—this was, particularly for single women, their most significant asset as they sought the economic safety of marriage. A jilted woman was suspect due to her tarnished reputation; a seduced woman was considered ruined.”

Jane Armstrong Tucker was an unmarried Boston stenographer scratching out a living during the Gilded Age. She probably would have remained in obscurity were it not for her spirit of adventure and derring-do, which culminated in a unique offer: become a spy for Breckenridge. His lawyers hired her to find Madeleine, become her friend, and extract her secrets. Her salary: fifteen dollars a week.

The attorneys “wanted her to discover what sort of woman Madeleine was and see if Jane could convince her to settle for a monthly allotment. In the event of a trial,…Jane would keep the defense team informed of the plaintiff’s plans…Here was the great adventure Jane had yearned for in her youth; here was the escape from family duty she craved as a young woman…” If spy craft calls to you, as it does to me, read this book.

Tucker took on a pseudonym—Agnes Parker—and found Madeleine in the House of Mercy, a home for “fallen women,” a place that, as the author writes, was full of “shop girls seduced by leering customers, hometown girls fooled by false promises, and domestic servants abused in the household. Some girls had been in love, and some girls had not; some young women had been virgins before their fall, while others had been experienced. But all of these women had crossed a line; tricked, cajoled, deluded, or raped, they were unmarried, and either as agents or victims, they had been caught and crucified in an age of moral absolutes.”

She managed to convince the sisters who ran the home to take her in. Once there, Jane followed the advice of her handler at the law firm: “Get settled at the House of Mercy, he said, and rent a post office box under a fictitious name. He said to send him the key and box number, and that’s how they’d communicate—only in writing and using aliases. Not even Breckinridge would know her name—only him. Meeting in person was too dangerous…Proceed slowly, be exceedingly cautious, and make no mistakes.” Warnings you’d hear in any CIA flick and warnings that will keep you turning the pages.

DeWolfe reminds us that:

“… Jane had more in common with Madeleine than perhaps she was willing to admit…They sought a similar destination: directing their lives in the face of, and despite, the challenges women faced: working-class wages barely sufficient for the needs of life; glass ceilings for women professionals …whose expertise was questioned and mocked; rules of etiquette that served as a litmus test on social legitimacy; laws and cultural beliefs that limited women’s rights to property, fair wages, ambitions, reproductive health care, education, the vote; and practices like the sexual double standard—collectively denying women a full measure of personhood.”

DeWolfe’s crisp writing takes readers by the hand and guides them through situations that, given pseudonyms and lots of little lies, could be confusing were it narrated by a less capable author. Also, to accurately report a trial requires sedulous attention to details, lest the reader lose track of what happened. DeWolfe manages this task. What’s more, she lights up the culture of the time, not only its strict moral codes, but its women’s gut fear of childbirth. She touches on the racial attitudes and the vestiges of slavery (a former slave testified in the trial.)

In many ways, her work resembles J. Anthony Lukas’ 1997 book Big Trouble: A Murder in a Small Western Town Sets Off a Struggle for the Soul of America. Both volumes display American culture and politics at the turn of the century—Alias Agnes in the Gilded Age of the 1890s, Big Trouble in the America of 1905. Alias Agnes describes a civil trial; Big Trouble, a murder trial—the assassination of Idaho governor Frank Steunenberg. And both focus on espionage. Lukas’ book discusses private detective organizations like the Pinkertons, who worked against organized labor, and it featured a paid informant for a mine owners association.

If you like legal history, you will enjoy this book. If you appreciate characters who are scrapping against the world, as both Jane and Madeleine were doing, take my recommendation and buy this book.

Anthony J. Mohr served for twenty-seven years as a judge on the Los Angeles Superior Court and still sits on a part-time basis. His work has appeared in, among other places, Cumberland River Review, DIAGRAM, Hippocampus Magazine, The Los Angeles Review, North Dakota Quarterly, War, Literature & the Arts, and ZYZZYVA.

Anthony J. Mohr served for twenty-seven years as a judge on the Los Angeles Superior Court and still sits on a part-time basis. His work has appeared in, among other places, Cumberland River Review, DIAGRAM, Hippocampus Magazine, The Los Angeles Review, North Dakota Quarterly, War, Literature & the Arts, and ZYZZYVA.

His debut memoir Every Other Weekend—Coming of Age With Two Different Dads was published in 2023 and placed first in nonfiction in the Firebird Awards, first in nonfiction in the Outstanding Creator Awards, and first in the autobiography/memoir category of the American Writing Awards. Australia’s BREW Project named it 2025 Memoir of the Year. A six-time Pushcart Prize nominee and a 2021 fellow of Harvard’s Advanced Leadership Initiative, he reads for Hippocampus Magazine and Under the Sun. He is also the co-managing editor of the Harvard Advanced Leadership Initiative Social Impact Review.