Reviewed by Nan Bauer

I have a rule when it comes to biographies: Don’t immediately turn to the photo well. If I head there first thing, it’s just looking at a stranger’s album with polite interest. The pictures come to life when I study them in context of their place in the biography.

I have a rule when it comes to biographies: Don’t immediately turn to the photo well. If I head there first thing, it’s just looking at a stranger’s album with polite interest. The pictures come to life when I study them in context of their place in the biography.

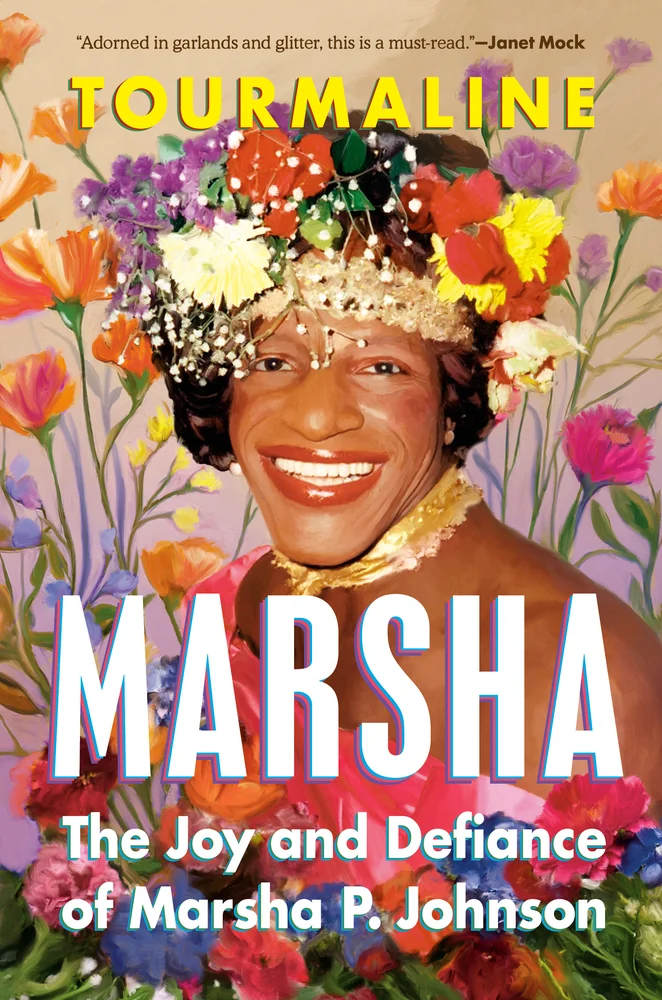

Well, this is the biography of Marsha P. Johnson; the P stands for “Pay It No Mind,” one of Marsha’s favorite maxims. That’s exactly what I did with my rule, turning first thing to the photos in Tourmaline’s Marsha: The Joy and Defiance of Marsha P. Johnson (Tiny Reparations Books, 2025).

Like this biography, the photos arranged in rough chronological order—except, like the story, when they aren’t. Tourmaline gives us a Marsha without limits, a Marsha who gets to be the multitudes that she contains in whatever sequence makes sense. Chaotic? Sometimes. Compassionate, exuberant, and inspiring? Always.

Tourmaline foregrounds Marsha’s story with her own in her introduction. Drawn to the heart of the West Village after college in the early 2000s, Tourmaline found Christopher Street to be a “sanctuary for young queer and trans people of color like myself, buzzing with an electrifying joy.” The more she spent time in the neighborhood as an activist and artist, the more she began to hear about Marsha.

What results is as perfect a union of biographer and subject as I’ve read. Tourmaline assembles facts as if they were small tiles that create a glorious mosaic of Marsha. Beginning in Elizabeth, New Jersey in 1945, we follow young Marsha to Sunday school—throughout her life, she professed a deep love of Jesus. She’s in her element in full drum major regalia leading parades at her high school.

But she’s not accepted, at least not early on, by her mother, who beat and stripped Marsha of her female clothing. New York C/ity was just a bus ride away, Marsha began sneaking there while still in high school.

Decades before Disney coopted it, the area around the Port Authority and Times Square was a dangerous place. Sex workers, which Marsha would eventually become, were preyed upon not just by johns but by corrupt and brutal cops. New York’s bizarre “three items” law—you could be arrested for not wearing three items of clothing associated with the gender assigned you at birth—provided justification for abusing the trans community.

Yet Tourmaline credits Marsha’s often harrowing experiences in the city as an essential part in her evolution, the place where she began to create what would become a huge found family. “So much of the intention behind what came later in Marsha’s and other girlies’ lives—the bright international stage, the social movement work, the freedom to move around without being harassed—was dreamt up on Forty-Second Street.”

Music and dance lured Marsha down to the West Village and the Stonewall Inn, a gritty Mafia-owned bar that was one of the few places where trans people could get a drink and not be harassed; even in the gay community, transphobia was common. It’s in “The Stonewall Rioter” chapter that Tourmaline the reporter hits breathtaking stride. Her blow by blow of the actual Stonewall Riot, from the first shot glasses thrown—one of which almost certainly came from Marsh’s hand—to the liberation that followed is riveting reading, the excitement, danger, and joy of the moment pulsing off the page.

Tourmaline clarifies Marsha’s Stonewall pivotal role in the historic uprising, one downplayed throughout her lifetime and after it, partly because in Marsha’s own telling she muddled the dates. Rather than turn Marsha’s words against her, Tourmaline addresses the slippery aspect of memory, as well as the roles that Marsha’s own trauma and mental health issues played in her inability to remember things precisely. “Marsha’s account, with all its fire and chaos, was like a fever dream of the raid and the riots. Let Stonewall be both firmly in the early morning hours of June 28 and on her August birthday. Let her be there, throwing the shot glass heard ‘round the world, and uptown at a party, celebrating life.”

Stonewall lit activist fire in Marsha. When one of the biggest advocacy groups to form in Stonewall’s wake, the Gay Activists Alliance, spurned trans people, STAR— Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, “transvestite” being the term by which Marsha referred to herself—was born. The Black Panthers’ dedication to community and freedom from poverty inspired her to write the STAR manifesto, a concise statement of rights that remains tremendously relevant.

For a brief time, STAR had its own safe house where trans people, particularly young ones, could stay for free. Marsha envisioned much more: a 24-hour STAR hotline, a recreation center, help with medical care and bail. STAR was short-lived—the tenants would face eviction within a year of its founding. It seems amazing that Marsha willed it into existence at all, a testament to her determination and huge heart.

Marsha had long dreamed of performing onstage, and in the mid-70s began to find various venues, which she inevitably stole from the moment she walked onto them. Two downtown groups, the Angels of Light and Jimmy Camicia’s Hot Peaches, became performance homes for her, and the latter group toured LA and London, giving her a chance to see more of the world.

Tourmaline documents what seems to be every single fact she could find about this phase: what Marsha wore, what she sang—notoriously off-key—who she performed with, which theaters, the fact that Andy Warhol asked her to pose for a portrait. “Marsha wove together activism and performance into a fabric that was a confluence of social movements: the downtown art scene, antiwar activism, Black Power, and gay liberation.”

As AIDS began its hideous crawl through New York, claiming many of Marsha’s friends, she provided care, cleaning messes, laundering sheets covered in shit, visiting the sick, participating and organizing AIDS walks and dance-a-thons. She continued all of it even in the wake of her own HIV positive diagnosis in 1990.

Protease inhibitors were in the very near future and not a reality for Marsha. She began to talk about “crossing the River Jordan,” her euphemism for death. Still, Marsha performed, though less often and no longer touring. She nurtured, gave care, marched, including at the head of New York’s 1992 Pride Parade, alongside her close friend Sylvia Rivera, who she’d known since her Times Square days.

Within a week of that final parade, her body was found in the Hudson River. Police dismissed the death as suicide until her case was reopened in 2012. To this day, the case is unresolved.

Tourmaline explores every possibility before leaving us to our own conclusions. Some friends of Marsha believed that she was simply finished and that she decided to take her own life; others felt that the pain of losing so many people she loved, as well her physical and mental pain had put her on unsteady ground, that she had hallucinated that she could walk on water. Others fiercely deny suicide as a possibility. It’s great, riveting reading.

It’s a tribute to Tourmaline that, when watching Michael Kasino’s documentary Pay It No Mind after reading the book, I already felt like I knew Marsha. And since reading the book, I see her so often throughout our culture. There she is, jamming with Beyoncé on “Virgo’s Groove”—they share the star sign—loving the Renaissance album. She’s the spirit animating the mother figures on Pose, whispering in RuPaul’s ear on Drag Race. She’s in small acts of kindness done whole-heartedly. In my garden, I think of which flowers I’d give her for her hats.

“It is my dream that every reader of Marsha’s story will take away from it the permission to be their whole self,” writes Tourmaline in her intro. It’s a big, Marsha-sized dream, and a beautiful one. In writing Marsha: The Joy and Defiance of Marsha P. Johnson, Tourmaline allows us all a vision on how to achieve it.

Nan Bauer is a writer currently based in Southeast Michigan, and is completing a memoir on life on the front lines of AIDS during the late 80s in New York and Key West. She has written about food and culture for Ann Arbor Current, Toledo City Paper, Edible WOW, and other regional publications. She is a decent cook and excellent at riding camels. Find out more at nanjbauer.com and/or follow her @nanjbauer