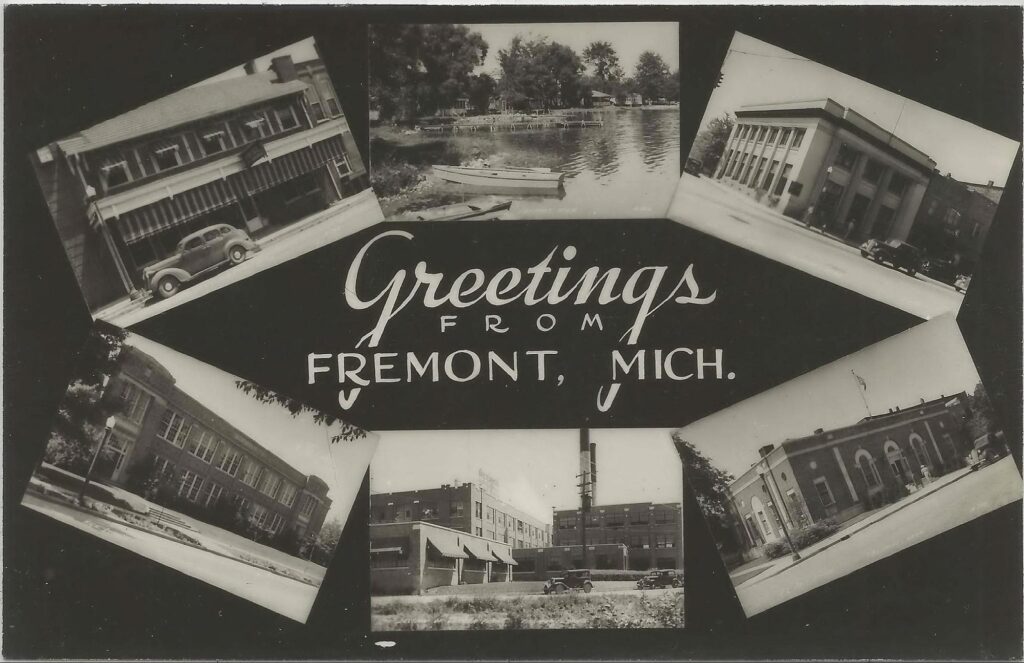

Theory of Welcome: Boredom opens doors. When we moved to my rural hometown of Fremont, Michigan, with its tall, blond, blue-eyed descendants of Dutch settlers, my family’s neighbors and colleagues quickly took us under their wings. They were motivated by a delectable combination of kindness, curiosity, and relief. Also, the closest Chinese restaurant was an hour’s drive away and my mother made a mean egg roll.

Theory of Buoyancy: When stepping off a dock into unfamiliar water, choose an inner tube over lead weights if you can. When I was three, a kid from Sunday school in Fremont told his grandfather that I was from the Philistines. When I was twenty-five, a man in San Jose told me that Thai food was his favorite kind of Chinese food. At thirty-three, a boyfriend’s family member in Boston asked me if I knew karate. Deep down, there’s not much separating a three-year-old and a thirty-three-year-old, and the difference between a new friend and a bony-eared assfish is their tone of voice, the light behind their eyes, and their open face. Sometimes, floating or sinking is up to you.

Theory of Features: My glasses slip because of my older siblings. Every chance they got during the first decade of my life, they pressed on my nose like they were launching a nuclear missile attack while joyfully exclaiming, “Punky nose!” If I formed a protective cage over my nose with my hands, they pushed in the whole cage, in effect forcing me to punky-nose myself.

Theory of Creativity: I’m resourceful because my parents didn’t have the money or inclination to buy toys when we were children. Props for our games consisted mainly of pencils, paper, snow, rocks, and sticks. This makes it sound as if we were Amish, but we weren’t. We were just regular Protestants.

Theory of Assessment: When I was growing up, teachers sometimes gave me As not because I earned them, but because the reputations of my siblings paved the way for me. Plus, I was Asian in a sea of white kids, and who was I to question implicit bias, pity, or anything else that worked in my favor?

Theory of Decency: My paternal grandmother planted my moral seeds. When I was a little girl, she told me stories about blind beggars on the streets of Cebu City who kneeled with their cupped hands outstretched towards passersby, and she observed my tears with satisfaction. Her only shopping was at Valueland, where she’d get five yards of whatever fabric was on sale and hand sew it into clothing for Philippine orphans. Goodness seemed perpendicular to extravagance, and thus I was never attracted to investment banking, business, and other finance careers, nor did I admire the boys from my dorm at MIT who skipped class to fly to Las Vegas, count cards, drink champagne, and sleep in comped luxury suites. If it weren’t for her, I’d probably have a lot more cash now, pursuing, spending, and stashing it, money begetting money as if greenbacks grew on trees.

Theory of Futility: My father was hard on my big brother because he thought he could change his gentle nature through sheer force and will. But I idolized my brother, who had an imagination more expansive than the night sky and whose magic enveloped me like a nebula of stars. Twenty years later, we were both living in San Francisco and I was a fully fledged fruit fly in the produce section of Dolores Park, wishing him godspeed as he scooted off to throw back drinks at the Stud. King Lear wasn’t the only one who boarded a bullet train to mayhem when he tried to whittle his kids into other shapes.

Theory of Maladaptation: Despite what forty-four TED Talks say about venturing out of one’s comfort zone, maybe I should have left basketball to my Teutonic classmates, who had legs like quarter horses and grew up watching people hurl themselves at each other to possess an orange ball. I was small and raised to be nonaggressive. So in middle school, I was eye level with everyone’s clavicles, and when they charged at me, instead of dodging or pushing back, I closed my eyes and bared my gleaming orthodontia, waiting for impact. This led to a few bloody shoulders and cries of “you bit me!” They were mistaken. Then and now, I preferred dark meat. These days, I often wonder: What am I doing terribly now that I won’t recognize until much, much later? The answer: certainly many things. Yet there is no way to see until I see. The bleeding is unavoidable.

Theory of Visibility. Our lights illuminate everyone. When I was sixteen, while quizzing me for a chemistry test, my mother spontaneously reeled off the ionic charges of the elements on the periodic table from memory, having learned them in pharmacy school three decades prior. Until then, I’d known her as someone who mostly cooked, hung laundry, denied my requests for sleepovers, and hissed at me to lower my voice in public. For the first time, I understood that instead of the life she got, she could have had one of paychecks, restaurant dinners, books in bed, and grateful patients. A movie reel of her other existence began playing in my mind, and it hasn’t stopped since. Thank you, she would have heard all day long. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you.

Theory of Individuality: A lack of context is freedom. For the first third of my life, I didn’t know that being good at math, playing musical instruments, and finishing a book every week was cliché. My likes and dislikes, and strengths and weaknesses, were completely my own. Assuming no ethnic predispositions also meant I only blamed myself when I tapped a deer and put a dent in the hood of the red car. Now that I’ve been in the world for a while, I grin and say that a “B” is an “Asian F,” but AAA is still going to raise my premium if I total my car.

Theory of Self-Knowledge: Our skin sacks and the memories, fears, and desires they contain are our only true possessions. So I can’t get on board with a common Asian custom of withholding health information. When my maternal grandmother was diagnosed with stomach cancer at the age of 90, her children kept the news from her. Supposedly, this allowed her to carry on without fear in that big house in Cebu City, scolding the house boys who sat on the roof when they were bored and locking bedroom doors to safeguard valuables. Not aware it was time for goodbyes. Thomas Gray wrote that ignorance is bliss, but he was referring to three hundred schoolboys gamboling on the Eton green in 1747, and my grandmother never donned a tailcoat nor a pair of pinstriped trousers in her life. When it’s my turn, give me the red pill and a choice of gelcap, chewable, or sublingual.

Theory of Safety: Immigrating burned all the fuel in my family’s hazard tank. So when I was offered barely enough at my first job out of graduate school to pay my student loan bills and rent a 200-square-foot studio apartment along the foggy panhandle of Golden Gate Park, I not only accepted the salary without negotiating, I also stayed for eight years, because I was taught to keep my head down and Not. Under. Any. Circumstances. Rock. The. Boat. Nor ask for more, à la Oliver Twist. For imagine the horror of repudiation. Feel the ravenous wind when I walk the plank, the cold spray of uncertainty as I struggle to maintain balance. Here be dragons.

Theory of Appearances: Modesty has a cost. My father, who prided himself on spending money on only books and education, thought I should get married in my hometown church, which was familiar and free. When I mentioned an art museum with a view of the Golden Gate Bridge, he asked, “Who do you think you are?” In the end, my fiancé and I chose a country inn on a road lined with eucalyptus and cypress trees, and to save money I sewed runners to cover ninety-five feet of tables, assembled a hundred lucky bamboo wedding favors and centerpieces, asked my siblings and friends to play the processional song on their high school instruments, and built a twenty-two tab spreadsheet to manage the rest. In microeconomics and life, labor substitutes for capital, but writing a check would have meant fewer pricked fingers.

Theory of Boxes: Overall, I have been helped more than hindered by Asian stereotypes. There are few downsides to others assuming you’re more gifted than you really are, but what has sometimes given me trouble as a seasoned professional is the presumption of diffidence. Reactions to the contrary vary. Once, a white male peer called me a dragon lady. Another time, an older white male business associate had me taken off a project. Whenever a white man suggests that I’m too aggressive, I have an overpowering urge to disembowel him.

Theory of Advanced Maternal Age: The decade I spent frolicking in the city before having a child was the source of my most painful contractions. At thirty-eight, my life of parties and boys and mountains and late-night runs at Kezar Stadium zoomed out like I was peering through the wrong end of a telescope. I couldn’t bring it back into focus. My new field of vision contained mainly wet wipes, pump supplies, burp cloths, and a hundred tiny socks that looked like they were made for chihuahuas. I used to say that I’d try anything once, but the kicker is that sometimes, once lasts forever.

Theory of Crisis: Other people’s emergencies don’t have to be your emergencies. This applies equally to missed deadlines, late rent checks, and nightmares. As I learned in junior lifesaving class, though, there’s a way to help without getting dragged under. The key is maintaining enough distance. Remove your swimsuit and use it to tow someone from the undercurrent, exposing your bosom and buttocks if you must, but bar a toddler from your bed unless you want to wake up at 4 a.m. with his toes jammed under your chin.

Theory of Peril: If the scene isn’t working, consider rewriting the script. It took two kids; four years of coordinating nannies, daycares, preschools, doctors, pediatric dentists, and matching hair clips; a threat of demotion at work; and personifying a pattypan squash dying on the vine for me to finally grant my heart its deepest desire: books, emotion, and language. My father believed that my trading science and a title for the arts and stories was dangerous, but risking uncertainty can be proof of security.

Theory of Exposure: Death decomposes the living. The police officer who pulled me over for speeding on an empty, straight country road two weeks after my father died glanced at my mother and children in the car, then looked at my husband and said, “Could you tell your wife to drive more carefully in the future?” My filters atomized by grief, I bit out, “That was patronizing.” If someone wants to treat me like a child, they should do it straight to my face, close enough to see the taste buds on the tongue I stick out at them.

Theory of Parenthood: Attention is to love as a mathematical proof is to a theorem. It is the QED of the heart. When I spent hours refinishing a bed frame for my daughter, I remembered how my mother had finished a small side table for my childhood bedroom. I recalled the tiny, sharp specks that marred the varnish and caught at the palm of my hand when it dried. Sweeping dust particles off my daughter’s bed frame between each step of sanding, conditioning, staining, and sealing, I wondered what else had drifted onto the flat planes of wood my mother worked. What hopes and resentments, dreams and discontents, made permanent? A testament of her devotion and care, flawed but everlasting.

Theory of Disruption: Havoc is a kid’s default mode. When my son was nine years old, he tried to throw rocks over our roof but instead broke our kitchen window. I thought it meant I’d done nothing right in raising him, because isn’t it basic common sense that one shouldn’t throw rocks at one’s own house? But remember how Kronos castrated Papa Uranus, and then Kronos, in turn, was chopped up by his junior mint Zeus and thrown into Tartarus? Justified or not, chaos is in children’s nature, like the scorpion on the back of the turtle who stings his own ride while crossing the goddamn river.

Theory of What the Fuck: There is no keeping the wild winds out, for we are but motes of dust in a room with a thousand open windows. When my son was nine-years-and-one-month-after-breaking-the-window old, he broke another kitchen window demonstrating to a friend what happened the first time. Then I knew I was right all along. I’d done everything wrong in the raising of that child.

Theory of Slippery Slopes: Despite its inviting softness and haze, the gray zone can be perilous. My daughter cultivated friendships in sixth grade without the aid of a cell phone as humans have done for the past 200,000 years, because even flip phones are quicksand, a crumbling edge away from cyber bullying, body dysphoria, predators, and depression. Remember a lesson from The NeverEnding Story: insidious and inescapable, swamps will swallow your beloved white horse while you stand there wailing with algae stuck to your gorgeous face.

Theory of Evolution: Change that comes at human pace is delicious. As a teenager in Michigan, I called myself a banana. A Twinkie. Yellow on the outside, white on the inside. In reality, my interior was a lemon vanilla soft serve twist, and negotiating the two sides encumbered me. Now, my biracial teen in California calls herself Wasian. I marvel at her blending. At her freedom to slip on and off of the stage, supernumerary or lead, in the shadows or the spotlight. At what I can learn from her about shouldering and shedding burdens. Every turn a choice, finally.

Ann Guy was born in the Philippines, grew up in Western Michigan, and now lives in Oakland, Calif. She received her MFA in creative nonfiction in 2020 and her MA in English with creative writing in Fiction in 2018 from San Francisco State University, where she received a Distinguished Graduate Award from both programs. Her writing and interviews have appeared in Craft Literary, River Teeth (Beautiful Things), Sweet Lit, Entropy, MUTHA, Ekphrastic Review, Literary Mama, Motherwell, Terrain.org, and elsewhere. She is at work on a historical and speculative fiction novel about migration, loss, and kinship. Find her at www.ann-guy.com.

I’ve read and enjoyed listicles, but this is a whole new dimension. Thank you for writing it.

test