Where will it end?

Where will it sink to sleep and rest,

this murderous hate, this Fury?

—Aeschylus, The Libation Bearers, tr. Robert Fagles

Because I don’t want anything to go wasted, nothing like the gibbous Romas slouching into red, pecked at once or twice by cardinals then discarded, the vines going brittle, golden, last-gasping—because I want everything to have been worth something, I go back to the girl who sat weeping that day on the bus ride home, inconsolable beside a parallelogram of June light, a space usually occupied by her third-grade classmate, Christine.

The last week of sixth grade: a time of kick-flips, bottle-rockets, first kisses in closets, then at pool parties in the deep end, slipping under water where the parents couldn’t see us, where they thought we were just holding our breath. Afternoons perfumed by the chemical scents of chlorine and neon hair gel, Sharpies gliding over glossy yearbook pages.

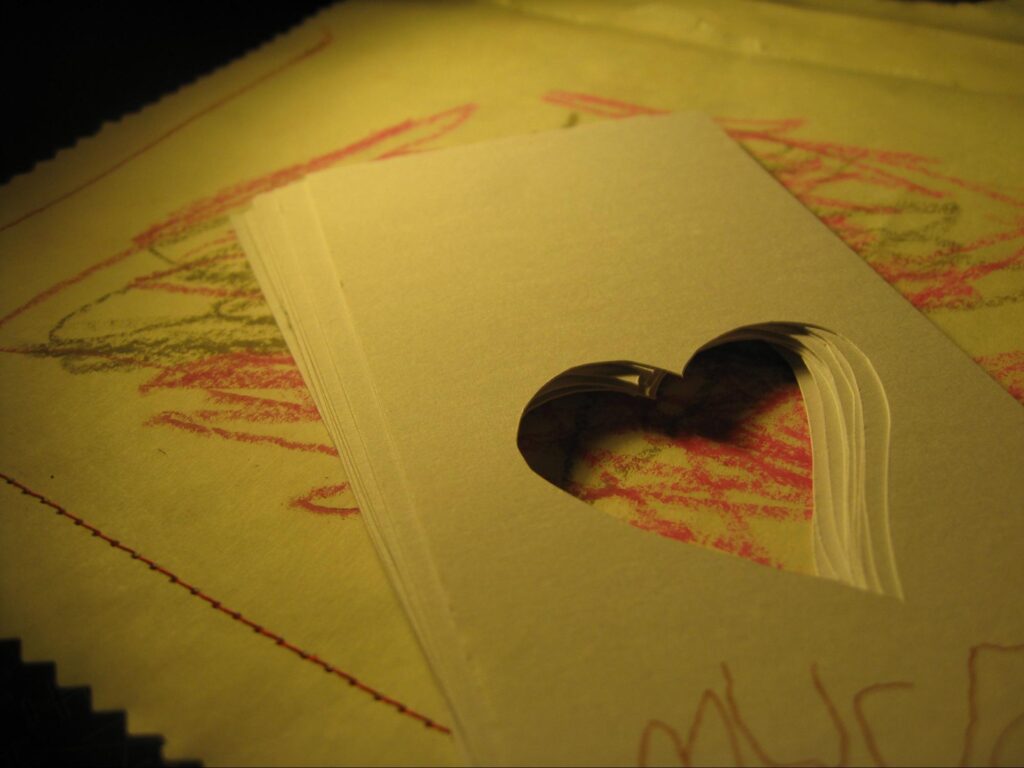

My friends and I had heard that morning that Christine wouldn’t be coming back, not the next day, not after summer break. Her classmates did drawings, watercolors, cut out misshapen hearts from construction paper, tacked them on with glue sticks, scrawling Christine’s name in uncertain cursive. Their teacher taped their works of art facing out the window so all who walked down the hall could witness the children’s grief, the awkward rosettes of their elegies.

It was a banner year for tragedy at Magnolia Elementary. A few months prior, my best friend Alex’s father had shot himself in the head. When that happened, it was us trying our hands at sympathy cards; it was us crying on the bus. When I went to Alex’s house to deliver the thick, uneven stack of cards, Alex’s mom crumpled into my arms, her tears soaking into my Thrasher t-shirt. Between sobs, she explained that sometimes people just feel so sad that their medication stops working, and then they don’t want to live anymore. After a choked silence, she peeled away from me, like a Band-Aid slowly tearing out hair. Alex and I spent the rest of that afternoon skateboarding in front of his house, doing pop shove-its and 180s off the ramp his dad had built for us just a few weeks before.

Maybe that’s why we all tried to not pay attention to the weeping girl whose name I can’t recall, or perhaps never knew, the brilliant So Cal summer light making the brown vinyl seat beside her hot to the touch. A few rows back, I was sitting next to Natalie, the girl I liked so bad it burned, our friends leaning over their seats, making up some lovey-dovey singsong to embarrass us. Our legs barely touching, hummingbirds hovering near nectar.

But the news we’d gotten earlier that day about Christine was different than what happened to Alex’s dad. The edges were even sharper, the glass too cloudy and warped for us to see through. We didn’t want to snap out of the chlorine-laced dream of our last days of elementary school, didn’t want to interrupt our skateboard tricks and nervous pecks, the secret fireworks we sparked in the alley behind my house.

So, we didn’t dare ask how or why Christine’s older brother, Paul, a straight-A eighth grader who went to youth group with some of my older brother’s friends, could have done what he did to his own mother and his only sister.

A modern-day Orestes if Orestes had slaughtered Electra too. If Orestes knew how to fire a hunting rifle and had the daring to do so at point-blank range. If Orestes had a six-year-old brother, and let that brother live, the whole nightmare happening while their father was away on business. In this Oresteia, Paul was tried as an adult, given two consecutive life sentences, the furies raving over their house on Canterbury Court, swooping down to peck, peck, peck at the half-formed fruit.

Today at the start of the yawning season I want to reverse the rot, climb back onto the bus, sit in those burning seats. I want to preserve the sobbing girl in honey and redo my card for Alex, mixing again the oval panes of watercolors in their plastic tray. I want to sneak back down into the deep end, slip below the shimmering surface, understanding, finally, that nothing, not even the fallen, desiccating tomatoes in the garden, ever goes to waste.

Gregory Emilio is a poet and food writer from southern California. He is the author of the poetry collection Kitchen Apocrypha (Able Muse, 2024), and his poems and essays have appeared in Best New Poets, Gastronomica, Gravy, North American Review, [PANK], The Rumpus, Tupelo Quarterly, and Southern Humanities Review. He earned an MFA from UC Riverside, and a PhD from Georgia State University. The executive director of the Georgia Writers Association, he lives in Atlanta and teaches at Kennesaw State University.

Gregory Emilio is a poet and food writer from southern California. He is the author of the poetry collection Kitchen Apocrypha (Able Muse, 2024), and his poems and essays have appeared in Best New Poets, Gastronomica, Gravy, North American Review, [PANK], The Rumpus, Tupelo Quarterly, and Southern Humanities Review. He earned an MFA from UC Riverside, and a PhD from Georgia State University. The executive director of the Georgia Writers Association, he lives in Atlanta and teaches at Kennesaw State University.

Image Credit: Flickr Creative Commons/Kim Love

test