Interviewed by Leslie Lindsay

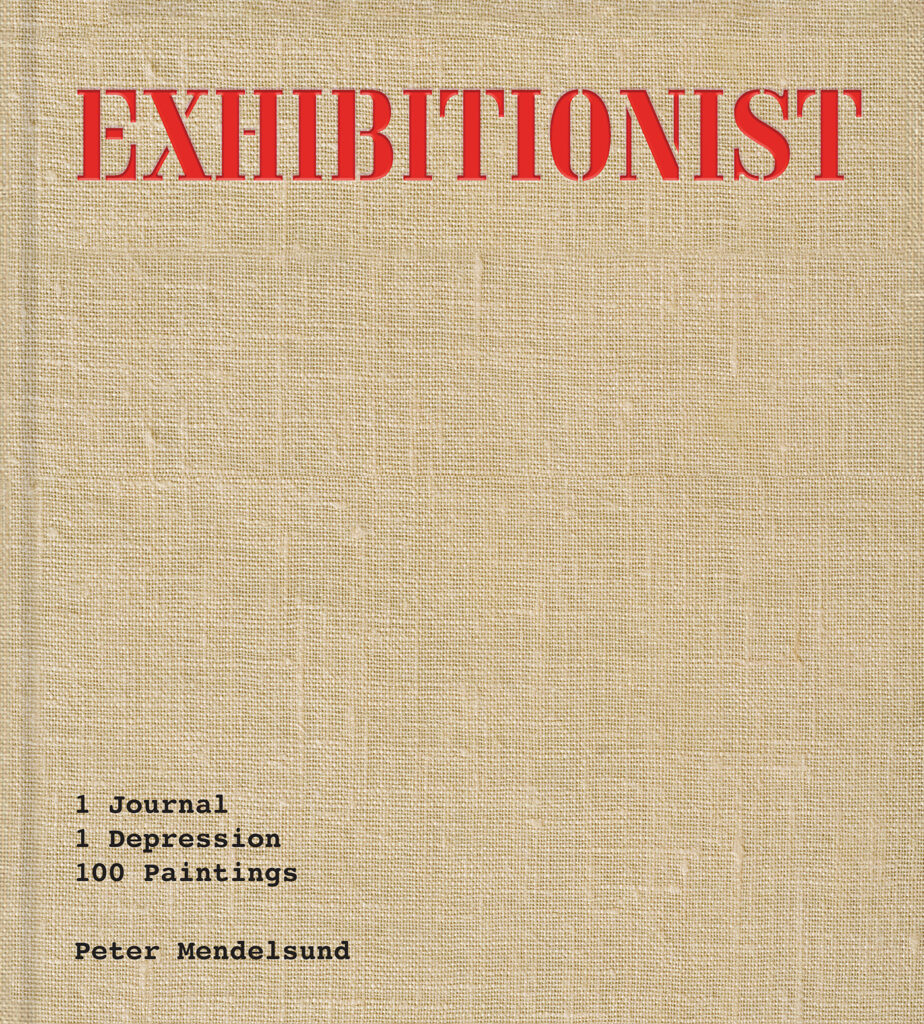

Today, I walked into an art exhibit in a small lakeside town. Not Peter Mendelsund’s exhibit, but I’d love to have seen that, too. Thankfully, I can still glimpse his harrowing and mysterious art in Exhibitionist: 1 Journal, 1 Depression, 100 Paintings (Catapult; June 2025), the author/artist’s response to his debilitating depression and the pandemic. What does art do, but show us what exists beyond, in the gaps, of our pain?

Today, I walked into an art exhibit in a small lakeside town. Not Peter Mendelsund’s exhibit, but I’d love to have seen that, too. Thankfully, I can still glimpse his harrowing and mysterious art in Exhibitionist: 1 Journal, 1 Depression, 100 Paintings (Catapult; June 2025), the author/artist’s response to his debilitating depression and the pandemic. What does art do, but show us what exists beyond, in the gaps, of our pain?

Exhibitionist is at once a memoir — a journal — and an art book. It’s utterly mesmerizing, a darkness of text interspersed with the vibrancy of paint splattered on canvas, a true duality in melancholy and making. One should note that Peter Mendelsund, while gifted in many artistic expressions, had never painted before. He writes, “I do not know what a painting is at all. I do not know what a painting is, or why it is. I do not know what a painting is for.”

Organized in one hundred numbered, mostly linear journal entries, Exhibitionist is highly immersive, gorgeously packaged work I could not look away from. While it’s deeply reflective and personal, Mendelsund draws the reader in with universal themes such as addiction, family, writing, music, silence, photography, philosophy, and more. This is a work about holding on and letting go. Mostly letting go. But you have to hold the book in your heart and mind, ‘enter’ the New Hampshire barn, if only for a moment, where the work was created for its alchemy to work. Mendelsund writes, “Its full meaning only conveyed upon completion. This force, this momentum, this drive, this voltage — flowing into a circuit, work to work — is built into the meaning and structure of ‘sentence.’”

“A sentence,” he continues, “only lasts for a period.”

One might hear ‘sentence’ and ‘period’ and equate it with prison. In some regards, that might be how one describes a debilitating depression. It may be how some viewed the isolation of the pandemic. It may be simply a moment in time.

Take a seat on the bench at the gallery. Pull up a stool in that old barn. Let your eyes fall into a soft focus. Take it in. Absorb. Read the museum card. We’re here to make meaning.

Leslie Lindsay: Peter, it’s so wonderful to chat with you. You are the author of seven books, including the recently-released Weepers (FSG 2025), The Delivery, and What We See When We Read. Plus, a classically trained pianist and graphic designer — your work is on hundreds of book covers — and creative director at The Atlantic. But I know, as a creative person myself, we often don’t think we’re anything at all; we just are. It’s baked in.

You write in Exhibitionist, “…what I am is neither designer, nor writer, no pianist, nor painter. I feel, right now, that I am nothing more than the daily management of my mental health.” You go on to say that painting — as you did for the first time during this period — is ‘just another symptom of your chemistry.’ Can you expand on this? The idea that chemistry and creativity might be intertwined? Or, are they? And how do you identify yourself when others ask what you ‘do?’

Peter Mendelsund: Thank you so much, it is wonderful to chat with you as well. It’s hard, if not impossible to uncouple one’s being from one’s brain chemistry, and so I think what I meant there (when one writes a journal, one rarely knows what one means in any given entry) is that the act of painting was a symptom of the depression rather than an activity I came up with a goal in mind, or arrived at in order to alleviate that depression. That the paintings were almost excreted — like tears — as a result of the depression.

That said, in direct contradiction to the above, I like to think, probably as we all do, that we, ourselves, are more than merely our brain chemistry, and that there is a ghost in the machine, some metaphysical essence that is us. Our quiddity. These are age-old and irresolvable questions. And so it is very hard to say which “Peter” was making the art. The trapped soul seeking release, or a bunch of brain cells starved of serotonin and dopamine just doing what they do. I think ultimately it doesn’t matter.

As to self-identifying: I have a very hard time answering the question “what do you do?” My first impulse is to say “musician,” as that has been my longest practice and my deepest love affair. Then I think, “I’m a writer,” because I suppose I am, and it’s what I’ve spent the most time doing over the last six years. “Painter” still doesn’t feel like it fits, as I started so recently, and as it is tied intrinsically to the depressions. Frankly, the answer “I do a lot of things” doesn’t cut the mustard either, as it implies that I don’t really do anything seriously. That I’m sort of a dilletante. (Am I?) So it’s always a tough one.

LL: Let’s rewind to the fall of 2020. Rain on the drive. You’re pulling up to the farmhouse in New Hampshire. It’s the pandemic. You’re depressed. The world is a mess. Everyone is isolated. You see a barn. You search the property. You may or may not be abusing substances. Tell us how things unfolded a bit. I want to know what small voice prompted you to turn into the parking lot of a craft store and load up on cheap paint and canvases.

PM: Well I will say first of all that when we were up there, despite the tremendous feeling of alienation that the depression engendered (not to mention the physical isolation due to the pandemic) I found myself needing to be alone. Social interaction was too difficult for me then — especially, sadly, with my loved ones. I felt too raw, too unsteady, limp, self-recriminating. There was the tremendous guilt I felt about being a burden. So I would wander off. Sometimes on a hike, sometimes on a drive, sometimes an errand, sometimes just to the barn alone. These excursions didn’t make me feel better per se, but they obviated the need to be around others and perform “improvement” and “well-being.”

Anyway, one afternoon I drove off to the nearest town, to the Home Depot, to pick up some hardware (I can’t remember what for) and saw a Michaels crafting store and went in. When I came out, it seemed I had bought a bunch of art supplies. That’s what it felt like: “I seem to have done that.” To this day I don’t know what led me in there. I never had the thought, “maybe I should paint.” Or thought, “maybe a project would help.” I was in a trance. A dream state. I like to think someone inside of me (that “small voice” you speak of) knew something the rest of me didn’t. But honestly, the voice was so small as to be almost completely inaudible.

LL: For a while afterward, you drive to the nearby town for provisions and hear the art supplies rattle in the trunk. You let them. You journal. But you’re not reading anything. Or playing the piano. You’re not writing, either. Was that by design or necessity? Were you seeking a…blank canvas?

PM: I think these channels (fiction, music) were just too emotionally fraught for me to engage with. I was already in so much turmoil that the littlest thing could — and would — reduce me to tears. Music and fiction were just too emotively potent. What I needed was to be numbed. I wanted my heart and mind taken out of circulation. This is where the substance abuse came in. The interesting thing for me here is that, unlike fiction and music, painting didn’t evoke anything in me. And still doesn’t. This I also do not understand.

LL: Do you want to talk about the depression? Is it too obvious? How did you envision the journal entries? A way to mark time? Pass time? Or maybe something others would find, later? After your death?

PM: I’m very comfortable discussing the depression (especially now that I am free of it). I didn’t really think of the journal entries (at the time of their writing) as anything other than recording the hours and minutes. But I suppose in retrospect that, because it was so hard to speak about the depression with anyone, that at least I could speak about it to myself in that little book. There were moments when the journal did feel like a last will and testament (self-aggrandizing, but true), as you say. Later, when compiling Exhibitionist, the entries became simple raw material. Of course it was deeply affecting to read them back, for me, the man, now, but for me qua writer, this document became a text to work on. All my writerly tendencies were deep in my muscle memory.

LL: Toward the end of Exhibitionist, we get a greater glimpse of your family of origin. With art, there’s this concept of ‘another pass,’ more layers, which are revealed. My mother was an artist/interior designer/seamstress. She struggled mightily and took her own life. Your father attempted suicide several times. When you asked your mother about it, she initially denied, but then she said something like, “Oh yes…that time.” And there were other times, too. You mention something about the ‘fog of familiarity,’ that perhaps those close to you might say something like, ‘oh yeah…that checks out.’ Can you tell us more about that? And how it might pull through to the period of time at the farmhouse in New Hampshire?

PM: First of all, I am so sorry to hear this about your mother. And yes, the fog of familiarity is real. In my case, I wanted to excavate and understand all the murkiness. Not every family member feels this way. Others in my family have their own versions of this story, other narratives, mythologies that they draw on which constitute forms of surety, I think. Everyone copes in a different way of course, but a unified narrative can often help a family to mourn together. I myself feel that I was more damaged by there being an unexamined, prevalent narrative. The gaps in knowledge, the parts of the stories that didn’t add up, my puzzling over these eventually led me to seek answers (such as they were) and in the end this curiosity has helped me enormously (to heal).

To answer the last question, when I was in New Hampshire I was in pain to the extent that I would’ve done anything to alleviate it — suicidal ideation being the result of this — and it would’ve been impossible for me to have these feelings and not be put in mind of my father. It made me wonder if he had felt what I was feeling. It made me wonder if my condition was heritable. It made me feel an inordinate amount (again) of guilt (that awful “perhaps if I had only…” thinking that attends a death). But of course my father was also a fine artist, and so there were many parallels to draw on. He was simply present with me through this period in a way he hadn’t been since his death.

LL: Turning to the paintings themselves, nearly all are created with your non-dominant hand. Others created by attaching a paintbrush to the end of a broom handle. It’s as though you were attempting to distance yourself from the work, like touching it with a nine-foot pole, as Dr. Seuss might say. Was it that you wanted to create but not take ownership? Was it a dissociative act? Something else?

PM: (It’s funny: the nine-foot pole. During that period I kept thinking about the zen koan “where does one go from the top of a one-hundred-foot pole?” The idea there being, when nothing can be done, what does one do? I actually found this question helpful. Because when one can do nothing, one simply is.) Anyway I believe I painted using those methods you mentioned for two reasons. The first was, as you said perfectly, to “create, but not take ownership.” To self-annihilate as an artist (as a person as well). As a form of erasure. The second reason was purely aesthetic. I just found the works looked better without me in them. So I “systematically deranged my senses, as Rimbaud put it.

LL: The pages of Exhibitionist are mostly white, but occasionally, a page is stark black. Maybe another is grayscale. Others are mustard. Can you speak into this? Do the solid colors exact meaning, or are they present for more aesthetic reasons?

PM: I had to look back at the book just now to see if that was true, that I changed colors for the backgrounds! You are right I did. And what I recall thinking is this: the book is book-ended with yellow. A bright hopeful color representing 1. Before the depressions and 2. After them. The body of the book has black white and gray as background colors. This is for obvious reasons (depression) and then as things turn around, the yellow enters again. I can’t believe I forgot this.

LL: When I left that art exhibition in my small lakeside town, the world felt golden. Sure, we were experiencing a summer heat wave, the rainbow ribbons had gone limp; flat against the sidewalk. But there was something glinting in the distance. Inspiration, I think. Viewing other’s art was like putting on my glasses. Suddenly, I could see. What had previously felt inert, felt alive. I was ready to create. Might that be something that caught your eye? The weather? Other people? Your space in time?

PM: I think what caught my eye after the depression lifted was…everything. All the things outside the locked room — the prison cell — that was my mind. Simple, ordinary things. The sufficiency of these things. The sufficiency of the world. And so I could, and can, just, on my better days, be. And when I can just be, on those better days, I think what I see more clearly is: myself.

Leslie Lindsay

Staff InterviewerLeslie A. Lindsay is the author of Speaking of Apraxia: A Parents’ Guide to Childhood Apraxia of Speech (Woodbine House, 2021 and PRH Audio, 2022). She has contributed to the anthology, BECOMING REAL: Women Reclaim the Power of the Imagined Through Speculative Nonfiction (Pact Press/Regal House, October 2024).

Leslie’s essays, reviews, poetry, photography, and interviews have appeared in The Millions, DIAGRAM, The Rumpus, LitHub, and On the Seawall, among others. She holds a BSN from the University of Missouri-Columbia, is a former Mayo Clinic child/adolescent psychiatric R.N., an alumna of Kenyon Writer’s Workshop. Her work has been supported by Ragdale and Vermont Studio Center and nominated for Best American Short Fiction.

Wonderful, it reminded me of the haiku of Cid Corman.

Everything helps decipher

What nothing means