Interviewed by Amy Eaton

I met Tania Richard last summer when we were in the same line-up for You’re Being Ridiculous, a Live Lit show in Chicago. Her work left me thinking deeply about race, America, children, and the arts for weeks after I’d seen it.

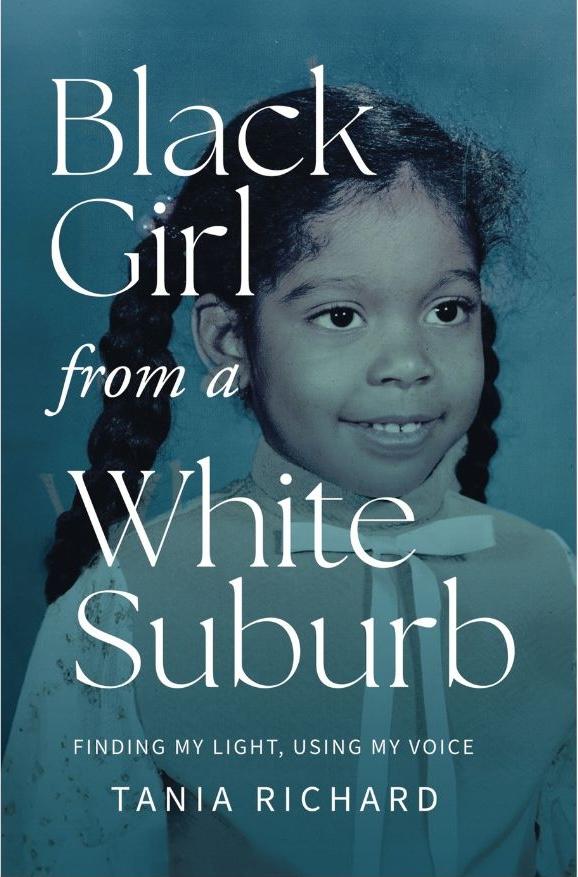

So when she offered me a chance to read an advanced reader’s copy (ARC) of her book — Black Girl from a White Suburb: Finding My Light, Using My Voice (Sept. 2025) — I jumped at the chance to hear more from her. While her life as an actress is fascinating, her point of view about what it’s like to be the only black person in the room as a child is a voice that is necessary, now more than ever.

Amy Eaton: Hi Tania!

Tania Richard: Hi Amy!

AE: I’ve seen sections of your book performed live and my first question is about structure. I opened the table of contents and it’s a list of plays — most of them very recognizable even to someone not in the theater world. How did you get to that?

TR: When I really committed to having this be a completed memoir, as opposed to podcast episodes, or essays which I’d thought about, I started to wrestle with taking all of these various versions of it and structure them. My experience in theater is one of the bigger constants in my life and I came across a memoir that created chapters based on individual women. That inspired me.

AE: And that was what?

TR: I Shouldn’t Be Telling You This: (But I’m Going to, Anyway) by Chelsea Devantez. Each chapter is centered around an influential woman in her life. The more I started to think about the book and about theater being such a through-line in my life, I wondered what would happen if each chapter was a play I’d either seen, read, or written. How did my life happen around it? I first fell in love with theater at my local library growing up in a suburb that didn’t offer a lot of opportunity for me to see myself reflected. But writers like Tony Kushner and Lorraine Hansberry gave me a glimmer of what might be outside of that suburb, so that was it. That was the framework. And when that moment happened, there was no looking back.

AE: It’s interesting that you say you thought you could do this as a series of podcasts. As I was reading, I found myself wondering why this wasn’t a one-woman show? And it’s clear, with the training you’ve got in DEI and engagement, how, even on the fly, you can break stuff down for an audience who might not grasp the nuances you’re addressing and you can reach them in a way that they’re not accustomed to. It’s such a gift.

TR: Thank you.

AE: And it’s so important right now, my God, especially right now!

TR: In digestible ways, right? Which, as we all know, is through story.

AE: Yes, it’s like little tiny kernels. But I really could see this as a one-woman show.

TR: Actually, it is both a book and a solo show. It’s going to be in the LookOut series at Steppenwolf Theater on October 3rd and 4th!

AE: Oh wow! Congrats!

TR: But the solo piece happened because there was a point where I felt so isolated in the process, as all writers do. I needed to be in conversation with this, or I was gonna go nuts. And I thought, what if I turn it into a show? I learned so much in that process and it really drove me to the finish line.

AE: When you are a performer and a writer and you write your own work, there is this interesting conundrum of: things you write for the stage and things you write for the page. Do you find that there’s a difference? Do you have a different process for either kind of writing?

TR: There’s a difference. A quick example is in the book I have a reference in the first chapter to Toni Morrison’s Recitatif, the short story. I talk about that very clearly in the book leading the reader to where I want them to go. We’ve discovered in the solo show, it wasn’t necessary. It was too on the nose. I had a version where I literally took the book out, and said “Toni Morrison says…” It just didn’t seem necessary. But that’s what I meant about being in conversation with the book through the solo show.

AE: You’ve done the show I co-host, MissSpoken.

TR: Yes.

AE: So, I’m writing for that monthly and every couple shows I’ll have a piece that I want to do something with. When I look at it afterwards, it’s different to the eye than it is in the ear. It really is a conundrum. Meanwhile, over the past dozen years, I just keep accumulating work.

TR: I used to not believe writers when they’d say it took them ten years to write a book because in my mind, I thought, they were exaggerating. No. You do a good hard three months and then go into a coma and forget about it.

AE: Like you do when you do a play!

TR: Exactly! Now I get it. Yeah, this took about ten years to finally get together.

AE: Yeah.

TR: It takes that long.

AE: It does. The book starts when you’re in 7th grade and it spans all the way up to Trump’s first administration and Covid; you become a long hauler. We get this huge span, which most memoirists shy away from. What made you take the leap to get it all in there? I mean, if this was a play you could stage it as a trilogy.

TR: You know, I was worried about that. But the later experiences are so connected to my experience growing up in an all-white suburb, which landed me now as an activist, and fully embodied as a black woman in this country that we live in now. I think the structure is what allowed me to do that. I’m building this journey of plays that I experienced at the same time that these big developmental milestones and social issues crop up.

AE: While you’re performing the Song of Jacob Zulu, you’ve got huge things happening with Rodney King and the first World Trade Center bombing.

TR: Yeah.

AE: And you’re so young!

TR: I know! I was like twenty-one or twenty-two.

AE: And it was your first real gig at Steppenwolf?

TR: Yeah.

AE: And that show goes to Perth Festival in Australia and then to Broadway?

TR: To Broadway.

AE: That’s normal.

TR: I would slap someone if I heard them say that was their first gig.

AE: I was an acting major and my first gig out of college was with a Deaf and Hearing theater company out of Rochester. It was a one-year contract, but beyond that year I was clueless as to what I was going to do.

TR: Well, when you’re basically at the zenith in your first professional experience, there’s a learning curve of, oh, it’s not always going to be this way! But yeah, being young and it being the first time I was able to be in a predominantly Black cast—when all I knew was being around white people, it just it changed my brain chemistry. It was a life altering experience. The solo show covers that first arc. Technically, that could have been the whole book. But that experience is just the beginning. It’s like the moment I met myself. I was like, oh, hello, whole person with other people reflecting me as well!

AE: Your family was an immigrant family immersed …

TR: In this culture of whiteness. And so the story couldn’t end with the first time I was part of a majority, because I was just getting started, you know?

AE: A lot of the book is really about finding your people. And otherness. Whatever that definition means, racially, artistically, culturally, socially. I think that’s a really uniting universal theme. We all want to belong to something bigger than ourselves. And, of course, the most obvious thing right in the title is the whole racial component throughout the book.

TR: Yes.

AE: It’s there in the subtext throughout the entire book: This is a Problem. Here’s why it’s a problem. Have you noticed this is a problem?

TR: Having grown up in a white suburb and then my evolution into owning my identity as a black woman, that journey has allowed me to have a language that a lot of people don’t speak. And what I mean by that is, having grown up with whiteness as my default I understand it. And I can talk in a way – I’m not talking dialect, I’m talking about spending my entire childhood having to be “palatable.” I know how to do that as an adult without it costing what it cost me as a child.

AE: Right…Ooh, ooh, ow!

TR: And what I discovered was this intersection of my storytelling, my writing, my performing, my knowledge has now allowed me to be a bit of a translator. I passionately, passionately believe that the personal and the political intersected is power. I just wanted to move people into the gray area. Especially with some of the stories where it could be argued, well, that’s not about race!

AE: But the microaggressions are so deeply ingrained in our culture, especially in forward thinking white people.

TR: Oh, hell, yeah, I know!

AE: We have this attitude of thinking we can’t possibly be racist when maybe the first step towards making any real progress is to admit there’s no way not to be racist growing up in American society and then deal with how to work against that and do better.

TR: I try to say this in a way that people can hear it, and that doesn’t mean it’s diluted or muted or spoon fed. Now that I’m fully embodied in my identity, I don’t have to worry about being safe, right? So, I’m able to just put the questions out there. Challenge, provoke. That’s what I wanted to do. I wanted the people reading my story to say, “I am getting to know her. And it is a lot more difficult to dispute what she’s saying because the evidence is her life.”

And on top of that for people like me, as black people living in this country who have had similar experiences, whether they too grew up in an all-white suburb or just by being in this world. I want them to see themselves and realize and embrace that they aren’t the only ones who have experienced this sort of fun house mirror of being a marginalized person. In many ways you can describe my experience as trauma, because if, as a child, you can’t see yourself reflected, that is a form of trauma. I’ve been able to translate it into a way that hopefully reflects it for others who’ve experienced it too. And maybe hold people accountable for what role they might have played in that harm. One of my hopes is that somebody who reads this understands the importance of children seeing themselves reflected in their developmental years.

AE: That’s huge. I’m remembering the workshop I saw you do at American Blues, where you open it up to the audience to break stuff down. It was a little older, predominately white crowd.

TR: Yeah.

AE: And some stuff that came out of a few people’s mouths really made me cringe. There was a lot of labeling and othering and I thought, I’m just going to sit here and wait, cause this is interesting to see people process information and your story and see if something in them changes — even just a little!

TR: I really love those moments. I love the moments when I am able to be in front of a group and someone says something crazy and because of the steps I’ve walked in my life I can hold it for everybody in the space and help everybody move through it without anybody being sacrificed. (But I also know when enough is enough and how to nip it in the bud.)

AE: Yeah, it’s very therapeutic.

TR: Yeah, so it is truly that part of the book about discovering your superpowers and knowing how you can use them. I feel like translation is one of my superpowers, and it’s so fun to do. Because everybody else is like (eyebrows up) Oh, no! But for me? It’s, “This is great. Watch this!”

Amy Eaton

Flash ReaderAmy Eaton is a writer, Live Lit performer, director, and coach. She co-hosts MissSpoken, a Lady Live Lit show in Chicago. Published work includes The Coachella Review and Mulberry Literary. Amy is a Ragdale alum and the second runner up in the Daisy Pettles 2023 Women’s Writing Contest. Her Substack, I Yell at Buildings….but I’m nice to birds, is focused on bringing attention to the Live Lit, storytelling, fringe weird art making that makes Chicago the best city on earth.