Reviewed by Sarah Rosenthal

[A note to the reader: when the events of the memoir take place, the author River Selby used she/her pronouns and went by a different first name. Selby is nonbinary and currently uses they/them pronouns. In this review, I refer to them by their current name and use they/them pronouns.]

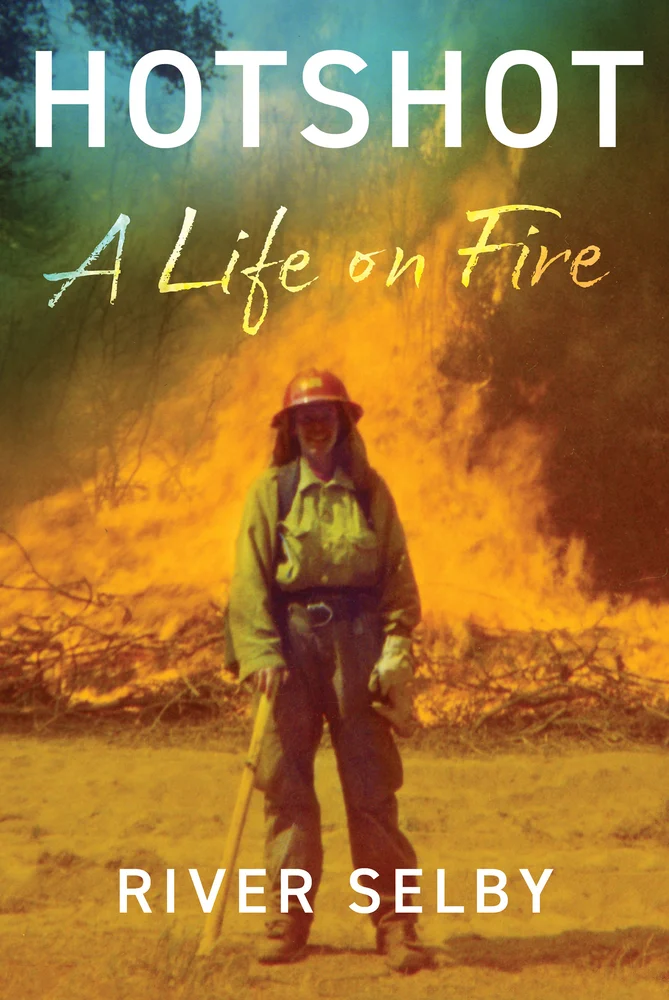

As I write this review, a dull scrim of smoke has descended upon Brooklyn, where I live. Wildfires in Canada are responsible for this haze, which obscures buildings in the distance that I typically take for granted as integral parts of my view. The haze, which last summer I might have shrugged off as a minor inconvenience, hits me differently now after reading River Selby’s debut memoir Hotshot: A Life On Fire (Atlantic Monthly Press; August 2025).

As I write this review, a dull scrim of smoke has descended upon Brooklyn, where I live. Wildfires in Canada are responsible for this haze, which obscures buildings in the distance that I typically take for granted as integral parts of my view. The haze, which last summer I might have shrugged off as a minor inconvenience, hits me differently now after reading River Selby’s debut memoir Hotshot: A Life On Fire (Atlantic Monthly Press; August 2025).

The book follows Selby’s journey as a hotshot firefighter in the western United States in the early 2000s. They describe their past as well as their experience as a hotshot within scenes; this is punctuated by lyrical descriptions of ecology, American history, fire science, public policy, and their own body as it transforms under immense physical strain. The result is an engaging researched memoir that is cinematic, meditative, and profoundly intimate.

A “hotshot firefighter” is one of the most elite American wildland firefighter positions. Hotshots are subjected to grueling physical fitness regimes in addition to specialized training to prepare them for the most difficult, remote, and complicated wildfires (the name “hotshot” refers to the fact that they are often sent to the hottest sections of a raging inferno). Despite their revered yet hazardous labor, hotshots were not considered “real” firefighters until 2022 and for many years they were not offered health insurance since it was considered “seasonal” work (this has changed, particularly as climate change has extended the traditional fire season).

Wildland firefighting in Hotshot is a brutal endeavour, one that often goes unseen and underappreciated. Throughout the memoir, Selby weaves their personal history as a hotshot in with narrative strands of environmental and colonialist history, which they argue is inextricable from the work of firefighting as it exists today. The history of fire in North America is the history of so many larger forms of systemic oppression, ones which Selby struggles with intensely throughout the book: environmentalism and climate change; the suppression of indigenous ecological wisdom; colonialism and manifest destiny; plus the desire to dominate and control the natural world.

Despite the arduous labor, however, firefighting is immensely attractive to Selby. They describe themself at this time as someone gravitating towards intensity, both physical and mental. “I had never considered being gentle with myself or realized I was punishing myself,” they write, though by the time the reader encounters this line, Selby’s fortitude and strength have long since been made apparent. Pushing themself was, as Selby describes, more akin to self-penalization in the wake of childhood trauma, shame, and hardship. Selby’s inclination to challenge themself physically, emotionally, mentally, and spiritually, however, came at enormous cost. From hiking to clearing brush to hauling gear up mountains to extinguishing embers buried beneath the ground, Selby’s narrator may be tender towards nature, but far less tender towards themself.

One way in which hotshots attempt to control wildfires is through controlled burning. But this idea of the controlled burn — a preventative measure — is one that has also been abused throughout American history by white settlers, to the detriment of the natural world. Selby’s own relationship to the land as well as the idea of a controlled burn is a complicated one. But ultimately, it serves as a means to cleanse both the soil and themself.

Selby leverages history throughout the book to underscore the cyclical nature of healing, harm, and regeneration within nature and within ourselves over time. Controlled burns were once used by indigenous people to live in harmony with the land itself. White settlers, however, oftentimes saw fire as a violent threat against their homes and businesses.

But regardless of who wields fire or how it initially sparked, Selby makes clear that it is the ultimate symbol of our desire for control: of ourselves, our bodies, our surroundings, and our futures. But just like the white settlers of centuries past, controlled burns can only cleanse so much. The land and its inhabitants — particularly Selby — still suffer when well-intentioned plans go astray.

Selby was one of a handful of women to serve as a hotshot firefighter in the early 2000s, and as a result they were subjected to intense sexism, misogyny, and harassment from many of their colleagues. Their experience of being a hotshot firefighter was extreme and dramatic on its own, but being a female hotshot specifically was territory far more treacherous than anything Selby could have trained for. Over the course of the book, Selby serves on multiple hotshot teams, some of which provided healing and cleansing, but just as often created new physical and emotional wounds that lasted long after they left the profession.

Before becoming a hotshot, Selby struggled with a difficult childhood and adolescence. Their mother lived an unstable life while suffering from serious mental health struggles. Selby abused drugs and partied as a teen. In addition to their transformation as a firefighter, Selby narrates their own internal struggles with an eating disorder throughout both their teenage years and their tenure as a hotshot.

While observing how nature responds to, and heals itself from, wildfire, Selby observes that not all healing is meant to happen in a neat and linear manner: “It will take a long time for the land to completely regenerate, if that’s what it’s meant to do. The premise of land ‘healing’ falsely assumes that ‘healed’ is an endpoint when in truth everything is cyclical. Nature has no endpoint.” Selby’s own healing throughout the memoir has no easy endpoint either, particularly when personal tragedy strikes near the end of the book. But healing and regenerating were never the end goal: rather, their suffering was a cycle of slow and deliberate growth to be embraced, not avoided.

Like the Western landscape, Selby is also continually evolving, growing, and possibly even regenerating in a series of figurative “controlled” (and not-so-controlled) burns. Over the course of the memoir, the reader sees them struggle with their physicality, sexuality, and gender identity; an endeavor particularly fraught given their status as the sole woman (or one of very few) on an all-male crew in a remote area. I admired Selby’s own relationship to regeneration and growth, working towards at least a semblance of outward peace with the land and an internal peace with their own body.

To be a hotshot is to lean into the contradiction of firefighting. Nature requires fire and destruction for rebirth. Humans need to contain wildfire to prevent casualties and protect the seeds of capitalism: businesses and so-called economic “progress.” Firefighters may be “saving” mother earth, the ultimate symbol of the feminine divine, but the only people deemed worthy of doing this work are men. Where a reader might see devastation and tangled ruins, Selby sees a way to learn from, and gain solace within, the paradox of wildfire: “There was so much I didn’t know. I was just a hotshot. I couldn’t see that the landscape needed cleansing by the flames I was supposed to extinguish.”

The history of wildfire in North America only further supports these inherent contradictions: “The first National Parks in the United States were established with the violent removal of Indigenous Americans. There is no justification for these tactics. At the same time, had they not been established, it’s likely that the land would have been deforested, mined, or otherwise exploited. We can hold two truths at once: that the lands were stolen, and that they were rescued from a harsher fate.” The ways we control nature can be harmful, but we also have the power to preserve it, if we choose. There’s a multitude of always-evolving complex truths which can live alongside one another as the land heals.

Selby provides a larger framework for American healing, one that touts the work of burning and saving as necessary yet dangerous sacrifice and salve, opportunity and surrender. As a society, which policies, attitudes, and beliefs must we save? Which should we allow to burn, so that something more beautiful can blossom in its place? And on an individual level, how much destruction is needed to make true recovery possible?

As I continue to revise this review, the haze outside of my window has lifted. But more wildfires proliferate in the news: this time in Ventura and Los Angeles counties out in California. I remind myself of Selby’s urging to embrace the contradiction that comes with news of a wildfire. I open space within myself for the destruction and danger that comes with the inferno, typically at the expense of society’s most marginalized and underprivileged; yet also, the reminder that that first spark is nature’s insistence upon creating room for something more sustainable and ecologically desirable.

Selby is clear: fire, however terrifying it might be, is never as simple as it seems on the surface. More often than not, the provenance of a roaring inferno can be both outside of us and within us simultaneously. And where there is devastation, there is also a chance to start anew. How we choose to heal ourselves, and our world, is up to us.

Sarah Rosenthal is a writer and lecturer at New York University. Her work has been featured in The North American Review, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, LitHub, Electric Lit, Bitch Magazine, The Sun, Creative Nonfiction, and elsewhere. Her newsletter, Nervous Wreckage, was selected as a featured publication on Substack in 2021. Learn more at www.sarahrosenthalwrites.com.

Sarah Rosenthal is a writer and lecturer at New York University. Her work has been featured in The North American Review, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, LitHub, Electric Lit, Bitch Magazine, The Sun, Creative Nonfiction, and elsewhere. Her newsletter, Nervous Wreckage, was selected as a featured publication on Substack in 2021. Learn more at www.sarahrosenthalwrites.com.