Reviewed by Anri Wheeler

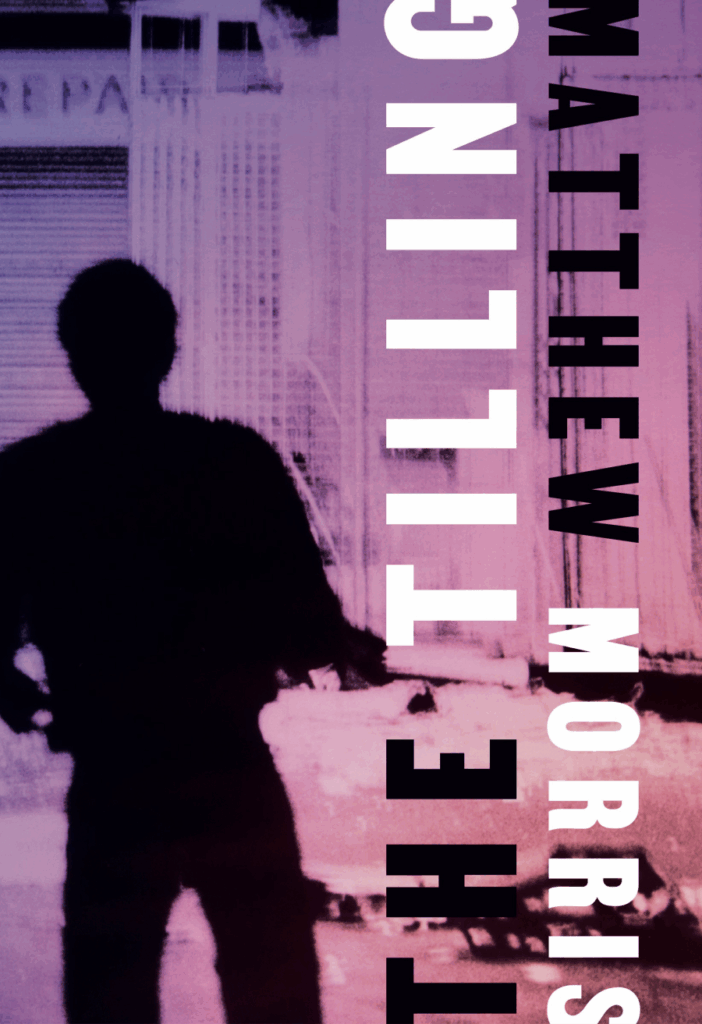

To read The Tilling (Seneca Review Books; December 2024) by Matthew Morris is to go along with the narrator on a journey of self-discovery. Winner of the 2024 Deborah Tall Lyric Essay Book Prize, the collection of ten essays puts Morris’ reckoning with his racial identity in conversation with famous Black writers and intellectuals, seminal works of popular culture, and myriad people — friends, classmates, acquaintances, aggressors — invited and unsolicited, who have commented on his race and skin color.

To read The Tilling (Seneca Review Books; December 2024) by Matthew Morris is to go along with the narrator on a journey of self-discovery. Winner of the 2024 Deborah Tall Lyric Essay Book Prize, the collection of ten essays puts Morris’ reckoning with his racial identity in conversation with famous Black writers and intellectuals, seminal works of popular culture, and myriad people — friends, classmates, acquaintances, aggressors — invited and unsolicited, who have commented on his race and skin color.

The son of a Black father and white mother, Morris is often seen by others to be white, leading to a persistent disconnect between the ways in which he self-identifies, and how others perceive him. This discrepancy between the expectations of others — some seeking for him to “turn up” parts of himself — and his own, fosters a pervasive feeling not being perceived in his totality. This push-pull lies at the heart of the book’s explorations, set up in its first essay “Tragic Mulatto.” Addressed to “American you,” the essay sits on the foundation of the tragic mulatto trope that Sterling A. Brown posited leads to a “divided inheritance” and Morris says can lead to “never belonging anywhere but with other mixed folks.” While exploring the ways the tragic mulatto stereotype is “both false and true,” Morris also provides the reader with an antidote, one both personal and systemic: wholeness. “This mixed half-body is a mixed whole-body. Whole. Don’t break it / into sections. See through it/it through, American you.”

In “Fucked Fable” Morris intersperses quotes from luminaries Sterling A. Brown, Zora Neale Hurston, James Baldwin, and Ralph Ellison, among others, with his analyses of how their thinking plays out in moments within his own life. In addition, we are confronted with the ever-present racist comments that

Morris heard from day camp, high school, college, and graduate school peers, illuminating the complicated ways Morris has metabolized his identity – filtered through the lenses and misunderstanding of others. The interjections of Brown et al deepen our understanding of the throughline from the foundational scholarship on the tragic mulatto stereotype to the everyday racism that shapes the life of Morris and all Black people in the US. The repetition of these moments showcase how banal they were in Morris’ coming of age; at the same time they remind us of the constancy of the sharp cuts repeatedly perpetrated against him. As Morris writes, quoting Andre Perry, “Even in passing he cannot transcend the pain.”

The fragmentation Morris feels when it comes to his racial identity comes through in the many rhythmic tangents on which he takes his readers via anecdotes that introduce us to the people and places that have shaped him, including Virginia and Arizona, both states he has called home.

In “The No Longer” and “Not the Ghost Of” Morris reflects his experience through the lens of Imitation of Life, a 1933 novel by Fannie Hurst, film versions of which were released in 1934 and 1959, respectively. I will admit: as a reader less familiar with the story, I found myself pulled out of the essays on numerous occasions, and also deeply appreciated how Morris used his analysis as a way to zoom out to the systemic. “I am not myself tragic, but the racial gulf is.”

The delicate dance of not knowing how to show up because he can be read as white, can cause Morris to feel like he doesn’t have the right to take up space, especially in places like his graduate Af-Am lit class. Yet with the assurance of his professor and a colleague who tells him he is a Black writer and to “own it,” Morris acknowledges, “the gulf is the problem, not the people.” Systems force us into bubbles and cages we don’t wish to occupy. And the way to take down systems is in community: “Maybe, if I…let this skin just be skin and no more, no less, I could wash the myth and tragedy right off this body—off me, off you, off us.” Morris makes clear that the racial gulf is tragic for all of us, in its presence “everyone’s made less than whole.” This reminded of me of oft-evoked quote by activists and scholars, “none of us are free, until all of us are free,” versions of which are attributed to Fannie Lou Hamer, Maya Angelou, and Emma Lazarus.

As a mixed race American, I deeply related to the explorations in “Pardo/Ghost Hand.” Morris is visiting Fort Worth when a fellow traveler, while standing right next to him, laments that she is “the only person of color” everywhere she goes. He writes, “like, damn, sometimes I wonder if others see mixedness in me even on occasion.” I immediately flashed back to a moment I was on a panel in grad school and a professor came into the space and commented it was unfortunate there were “no people of color” on the panel. I knew what she meant, and felt erased from the narrative. I too have tasted the euphoria of feeling so seen when others perceive me as mixed and/or Asian (an “unburdening” to use Morris’s words), coupled with the weight of needing/looking for this external validation in spaces and places of my life. Perhaps this is why I found myself wanting Morris to better transcend the need for this recognition by others, to find a quiet power in his own knowing; I want for him that which I have worked so hard (am still working) to carve out for myself. And there are several glimmers of his doing just this. As he says, “if I mean to do anything in my life besides write sentences, it is to puncture bubbles—for myself, for others.”

The collection culminates with “Till” a reference to the titular action of tilling, and also to Emmett Till. In this closing essay, Morris exploring the idea of a “bone-home”—a place you are buried, a place you return to, a place that ties you to your ancestors, by opening in South Carolina, his grandmother’s bone-home. He then zooms out, cataloging the number of Black (and white) bodies that were “lynched till inert, between 1882 and 1968.”

Tilling is an act of transformation. In the case of lynching, it is a brutal act that maintains and is built upon a system of white supremacy. In evoking those who were murdered this way, and Till himself, Morris signals how his lineage can be traced back to both victims and perpetrators of racial violence, hitting home one final time the way his ancestry cannot lead to one crisp conclusion, a reality for many Americans. “I’m pretty sure some of her ancestors were slaves. That some of them were enslavers,” Morris writes of his grandmother. A personal history, but also an encapsulation of the racial violence that was (and remains) foundational to this country.

Till is also until, up to a point. Morris has tilled his life, his memories, his relationship to himself — his ancestry, his body and skin — and others, excavating the roots that help him make sense of it all. This is a forever journey. The Tilling cracks open for the reader the critical flashpoints of Morris’ life to date from which he assembles a sense of wholeness, a sense of self. I hope readers will be able to find ways to do the same for themselves as they read this moving and vulnerable collection.