Interviewed by Leslie Lindsay

Today, while perusing the riverwalk art festival in my town, I wandered into an artist’s booth filled with pieces inspired by nature. Barns and fields. Dirt roads, orchards. The artist was a self-taught electrician who decided he needed something ‘more,’ something other than being a nameless employee. He had a handful of business cards, each contained a glossy image of one of his many works. I was drawn to the one of a farmhouse and barn, a pastoral scene. Maybe that’s because I live outside Chicago, in a town that has grown into a burgeoning suburbia, but is dotted with the occasional farmhouse and barn. I regret I didn’t purchase his art, but my walls are full.

Today, while perusing the riverwalk art festival in my town, I wandered into an artist’s booth filled with pieces inspired by nature. Barns and fields. Dirt roads, orchards. The artist was a self-taught electrician who decided he needed something ‘more,’ something other than being a nameless employee. He had a handful of business cards, each contained a glossy image of one of his many works. I was drawn to the one of a farmhouse and barn, a pastoral scene. Maybe that’s because I live outside Chicago, in a town that has grown into a burgeoning suburbia, but is dotted with the occasional farmhouse and barn. I regret I didn’t purchase his art, but my walls are full.

This is something I think Muriel A. Murch would appreciate, the merging of art with nature, complex with simple. Just because it’s ‘simple,’ though, does not mean it’s ‘easy.’ Weaving together Hollywood and agriculture, her upbringing in England, she chronicles food, family, farming, and friendship in such a way that feels not just full of life, but artful and poetic.

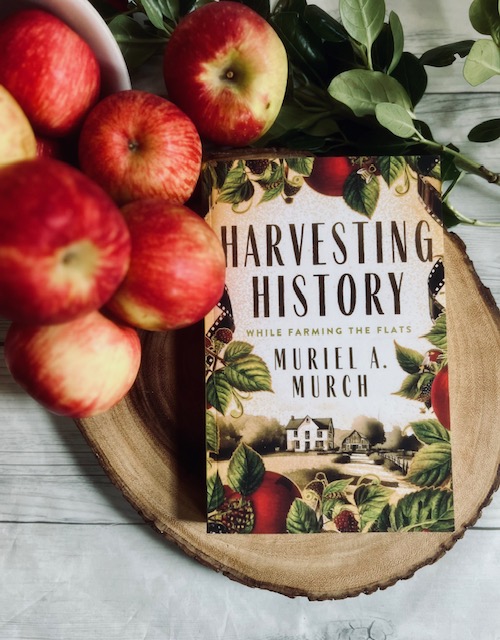

Organized in thirteen chapters with subheadings, plus a robust photo section at the end of the book, Harvesting History While Farming the Flats (Sybilline Digital First; March 2025), is a gorgeous, thoughtful book inside and out. A former nurse-midwife, Murch writes about her love of land, community, organic farming, the independent film scene, and so much more, it’s all juxtaposed by the sometimes troubling movement of urban development and Hollywood, which is anything but uncomplicated.

As I reach back to my own ancestral roots, I was so moved by Murch’s opening lines:

“Migration, moving away from one home to another, is sometimes voluntary, and sometimes forced. Quite often, we don’t know where home is until we are there.”

This was something I identified with. My ancestral family hails from the rolling hills of Kentucky, where they’ve farmed for well over two-hundred years. I feel a deep connection to the land, but also: beauty, hard work, and simplicity.

Please join me in conversation with Muriel A. Murch.

Leslie Lindsay: Muriel, thank you so much for taking the time to chat. I want to start with the very basics — the title. When I did a quick Google search, AI generated a response that the title could refer to ‘apartment homesteading…growing one’s own food while living in an apartment [flat]; urban farming.’ This question is two-fold. Maybe triple. One, can you talk about the evolution of your title, and two: oh my goodness — what are your [succinct] thoughts on AI? Three: the flat concept also pertains. Maybe AI is somewhat intuiting your early life in the UK?

Muriel Murch: Thank you for this conversation, Leslie. First the evolution of the title — the manuscript was holding as Farming the Flats while Harvesting History — farming to harvesting until I saw the first cover design — already almost perfect. There was something about the shadows in front of the farm house and across the driveway that led me deeper into the old memories. And I flipped the title, which kind of said, on its own. ‘What took you so long?’

AI is clever — too clever by half — if it was taking ‘flats’ to represent flats in the UK as opposed to apartments in the US it was in error. No wonder I am leery of it eating at my own thought process. I wonder if this is how people felt when the first Encyclopedia Britannica came out?

The Flats — known to those who know. The single road entrance into town, where Blackberry Farm sits, is known as Gospel Flats — and is where the churches were all first built. Today the Catholic Church has stayed on the corner, the Druids Hall morphed into Star Route Farms, while the Presbyterian Church was log-rolled into town. But to this day, the road remains Gospel Flats.

LL: I am looking at the cover — total crush — it’s got these warm colors, apples, a house and barn, tendrils of film strips along the side. It has a vintage vibe I’m totally digging. I want to say, based on the photos at the back of the book, it’s rendered from a photograph of your beloved Blackberry Farm. Can you talk about the process of designing the cover?

MM: All credit here to Alicia Feltman, a crowning jewel in the Sibylline Press team as their designer. Every cover I have seen from Sibylline Press speaks so well to each book. I cannot but imagine her loving every day she is working, reading and painting. When the time came I sent along some photos and thoughts; the ideas of the blackberry tendrils, the reels of film, do they support or constrain each other? Whichever, there is the nurturing harvest of art, apples and berries.

LL: Once, long ago, my husband had a dream to develop an apple orchard. He grafted trees and talked about land. You write about this in Harvesting History, in which you say, “Being an apple man or woman is not a path to riches, and barely one to self-sufficiency; but a love of trees, the husbandry, and the fruit as rich and aromatic as the love of any beloved…” Can you expand on that, please? Give us a little peek-behind-the-apple curtain? Do apples build community?

MM: Often folks, like your husband, have a dream, and when they have the space to plant apple trees. Maybe eating apples but without the knowledge of what they like, or what varieties will grow in their environment. And we ALL make mistakes! But the successes, the right tree happy in its environment, producing apples that taste better than you ever thought you could grow, is a precious moment. It takes years for the trees to produce fruit then suddenly there is too much for pies but too few for serious cider, so the windfalls fatten the deer and intoxicate the raccoons.

Or someone, like us, has a small press and gathers neighbors around to press their apple juice together. It is a project that creates a community, from families with young children, preteens holding onto work and machines, and a community senior day out. Sharing juice, learning about flavors, sweetness and tannin and – the importance of brewing hard cider — makes for a fine way to be together.

LL: Shifting a bit to the film/art side of Harvesting History, I was struck by another section in which you write about Walter, your husband, coming off a filming. Like many artists, you share, there is a ‘I’m finished’ moment, but, often that is just the beginning. There’s also this space where a creative person needs a respite. This is true for visual as well as literary artists. What is that moment like for you? What do you need after a spell of creativity?

MM: This is a tricky one. I’m only just learning about PJ days (at 82). For me, it is a slow realization that comes in stages: When the manuscript is ‘finished,’ though it never is, until it is taken away from you, is one stage then an acceptance by an agent or publisher, It is as if the respites are forced onto you by the rhythm of the work’s acceptance. For films this is different, there are deadlines, and budgets and more deadlines until the film is released in theaters. And then the work may not be over. Postpartum — publicity — awards events are bitter sweet with times to reunite with old colloquies in remembrance and gratitude for the shared work. The moments when I can say. “It’s done. I am glad I did that,” come in reflective stillness.

LL: Today, I was at a fine art market. Strangers were talking to one another, brought together by the bridge of art and creation. It was a beautiful thing. In Harvesting History, you write about the flower market of San Francisco, which has been in operation since the 1800s. It brought together the Italian, Chinese, and Japanese flower-growing communities. And still does. I love that. It’s truly the ‘melting pot’ idea our country was founded upon. Do you find the land builds community, or does the community build the land? Are farmers also artists?

MM: The land can do that, bring us all together. The Cowboy and the Farmer Should be Friends? Do you remember that from the 1950s film Oklahoma? Today, in the smaller rural communities which still hold agriculture I think it is true. I can’t speak for the big mid-western agricultural businesses which have such huge problems of their own making. Small farmers come together bonding over organic, sustainable, and regenerative practices, acknowledging each other’s strengths, weaknesses and commitments to the land. They/we help each other when they can and are often united to fight some common threat — usually governmental — that they see as more detrimental than beneficial to their collective good.

LL: One unique characteristic of Harvesting History is the scrumptious-sounding recipes peppered throughout. Can you talk about how those came to be?

MM: They arrived unannounced. It just didn’t seem right to write about the farming, growing and the harvesting without the sharing. I couldn’t just leave all that food in the wheelbarrow for the reader. These are mostly ‘old’ recipes, certainly not fine California Cuisine. Some even go back to my mother’s war-time kitchen, not to waste anything — ever. My cooking style mostly comes from farm-table feeding a big family, though there are a few treats in there. There are many more family favorites but I focused only on those whose harvest I wrote about, The crab fest is taken, and tweaked with her permission, from Peggy Knickabocker’s Simple Soirées from 2005.

LL: This is a big question, and perhaps the answer varies, but what do you hope others take away from their reading of Harvesting History?

MM: Hope — I don’t know — Harvesting History, like any book, is the author’s gift to the reader. Sharing this community that I know — from my perspective — with others. Sharing the stories of those who have gone before us with those who will come after us, those with dreams of their own of a simpler while hard working life. Sharing what is good about rural living within America’s rural communities. I believe that if — in whatever way — we have Agriculture, Art, and Service in our lives then we are blessed.

LL: Muriel, thank you so much for your time and generosity today. I’m off now, to sip that fresh-pressed cider.

Leslie Lindsay

Staff InterviewerLeslie A. Lindsay is the author of Speaking of Apraxia: A Parents’ Guide to Childhood Apraxia of Speech (Woodbine House, 2021 and PRH Audio, 2022). She has contributed to the anthology, BECOMING REAL: Women Reclaim the Power of the Imagined Through Speculative Nonfiction (Pact Press/Regal House, October 2024).

Leslie’s essays, reviews, poetry, photography, and interviews have appeared in The Millions, DIAGRAM, The Rumpus, LitHub, and On the Seawall, among others. She holds a BSN from the University of Missouri-Columbia, is a former Mayo Clinic child/adolescent psychiatric R.N., an alumna of Kenyon Writer’s Workshop. Her work has been supported by Ragdale and Vermont Studio Center and nominated for Best American Short Fiction.