Reviewed by Brian Watson

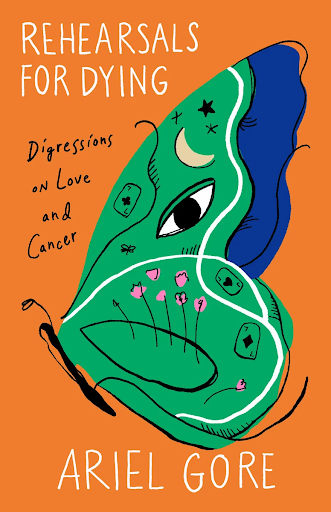

I wrote, and then mysteriously lost — I hate you, too, Microsoft Word — the first draft of this review a week ago. On most days, I believe in portents, which became one of the reasons I fell in love with Rehearsals for Dying: Digressions on Love and Cancer (Amethyst Editions; March 2025) by Ariel Gore. And when Word abandoned my draft, I wondered if the Universe had considered my draft to be unworthy. Spooked, I put the review’s reconstitution aside until this damp Sunday morning. Time to try again, with auto-save enabled.

I wrote, and then mysteriously lost — I hate you, too, Microsoft Word — the first draft of this review a week ago. On most days, I believe in portents, which became one of the reasons I fell in love with Rehearsals for Dying: Digressions on Love and Cancer (Amethyst Editions; March 2025) by Ariel Gore. And when Word abandoned my draft, I wondered if the Universe had considered my draft to be unworthy. Spooked, I put the review’s reconstitution aside until this damp Sunday morning. Time to try again, with auto-save enabled.

Do you write memoir? I do, and I hope you will join me in the inspiration I found within Rehearsals for Dying. Many a memoir workshop and seminar usually riffs on the following theme: you need perspective to write a memoir. You need to emotionally and chronologically distance yourself from the events you write about.

Generally speaking, this is fine advice, but the lack of that distance is what makes Rehearsals for Dying so powerful a read. I won’t lie: There were two times where I had to put the book down because my crying jags were so painful. The grief in Ariel’s chronicle of her wife Deena’s lived experience of stage 4 breast cancer is precisely effective because it is written from such a raw perspective.

Ariel speaks to this early on within the memoir:

“In grad school, I used to pore through books and papers and primary sources about things near my heart and experience. My professors called it “me-search.” I focused in, stepped back, focused in again. These practices allow me presence in my own life but also to view it at a distance — I can become a simultaneous spectator and chronicler. I describe a coherence that may or may not feel intrinsic. I hold difficult emotional experiences at arm’s length.”

And yet, the book opens as Deena steps from the shower one morning, musing whether her breast feels weird. From there, Ariel embarks on a memoir that is both lyrical — the chapters are flash-length and evocative — and researched. This combination of writing perspectives takes us beyond what the reader might expect of a cancer memoir, a genre that some might say has been overworked, and brings us into a somber kaleidoscope of emotions and facts.

Additional power is found in Ariel’s writing when she explores how medical providers are woefully inept when it comes to same-sex relationships. To wit:

“In dusty pink office after dusty pink office, nurses looked at Deena’s chest, then at me, then at her chest again, then at her file, like she was some kind of a puzzle, like she was the first butch woman they had ever met, like maybe we were in the wrong place because gender presentation and breast cancer had never before intersected in the entire history of the most common cancer among adults in the world.”

Not only does the reader experience, as Deena and Ariel do, the immorality of health care and insurance in the United States, where decisions are often made without input from the patient, but we also learn that manufacturers of cancer medications have corporate brethren that make the carcinogens potentially responsible for our diagnoses. We see how much money the Susan G. Komen organization raises while intentionally highlighting stories from those whose lived experience with cancer has the desired happy ending that capitalism so often demands of us, while at the same time paying the foundation’s executives six-figure salaries.

One of the best aspects of Rehearsals for Dying is Ariel’s focus on expanding the reader’s understanding both of breast cancer itself — the problematic diagnoses, the sometimes supercilious doctors, the medications and treatments — and also of those whose lived experiences include cancer. Particularly saddening for me was learning about Earl, a trans man who, on the verge of undergoing gender affirmation surgery, is told he has breast cancer, and the struggles Earl therefore endures in his attempts to find treatment from medical personnel who can both understand and honor Earl in that treatment.

But Earl is only one of many persons, friends, and interview subjects that Ariel introduces the reader to. As we learn more and more about the unique horrors Deena is forced to experience — the metastasis is unrelenting and the treatments are debilitating — Ariel brings in persons like Sia, someone Ariel knew from her Portland days, whose breast cancer also metastasizes to her liver. It is from Sia that we learn another horrifying aspect of breast cancer in the United States:

“Black women have a 4% lower chance of getting breast cancer but a 40% higher likelihood of dying from breast cancer compared to white women. Do that math. And please don’t gaslight me into imagining that the level of care I’m getting has nothing to do with my race.”

Sia’s death, noted both as a dream Ariel has where she and Sia are in Hawai‘i — “We didn’t drink. We didn’t talk about cancer. No storm rolled across the horizon” — and, two pages later, on a blacked out page with Sia’s name, date of birth, and date of transition, was one of those places where I had to put the book down to sob.

Another aspect of Rehearsals for Dying that I believe writers like me will value is the discussion of the language we use around cancer. In Deena’s words, Ariel’s words, and the words of others within these pages, I quickly realized the way our vocabulary around cancer, the battles, struggles, fighting, wars, victims, and heroes, isolates persons whose lived experience includes a cancer diagnosis. For many people, positing cancer as a battle to either win or lose shades the diagnosis with additional, unfair weight.

Not only is our understanding of the cause of cancer vague in so many cases, but when we then ask people who have been diagnosed with this horror that weakens and enfeebles so many to fight, how can we not realize that the inconsistent results of treatments and the abject pain of metastases, conditions no patient is ever in control over, that we then have to view cancer’s endgame as one which shifts the blame from the disease to the person living through it.

My goddaughter’s lived experiences (within a too-short life that ended on a Chicago street corner after a cruel hit-and-run) with breast cancer were excruciating. I understand the desire to valorize the experience of anyone whose cancer enters remission, but my goddaughter didn’t win anything, especially when the corollary of such a victory would be that those whose lived experiences with cancer end in death signify personal failure.

“Like those are the only two possible positions when one has cancer — losing or fighting.

“What about those too tired, sick, or traumatized to go to battle?

“What about those who run out of money?”

Or, as Ariel quotes Cat Thomas, one of the persons she interviewed, “So the question is, what if you can’t prevent disease or injury? What if we have no control over some of the things that happen to us?”

I will also say this about Rehearsals for Dying: Ariel is right, as the spouse of someone living through cancer, to call out those of us who allow our own unresolved griefs to block us from deepening connections with cancer and those diagnosed with it. This is, perhaps, a particularly American reality, as our citizens are rarely offered the time and space to comprehend any grief, but to read Ariel’s words chilled me (and prompted me to be better moving forward):

“Everyone I knew online said they were sending ‘love and light’ our way, but I couldn’t feel it.”

Brian Watson

ReviewerBrian Watson’s essays on queerness and Japan have been published in The Audacity’s Emerging Writer series and TriQuarterly, among other places. An excerpt from Crying in a Foreign Language, their memoir’s manuscript, appeared in Stone Canoe in the September 2025 issue. They were named a finalist in the 2025 Pacific Northwest Writer’s Association’s Unpublished Book contest, and in the 2024 Iron Horse Literary Review long-form essay contest. They also won an honorable mention in the 2024 Writer’s Digest Annual Writing Competition. They share Out of Japan, their Substack newsletter, with more than 600 subscribers. In 2011, their published translation of a Japanese short story, “Midnight Encounters,” by Tei’ichi Hirai, was nominated for a Science Fiction and Translation Fantasy Award.

Thanks for this amazing review, Brian. Maybe the universe wanted to delay you so that this published on Deena’s would-be 60th birthday!