Reviewed by Emily Webber

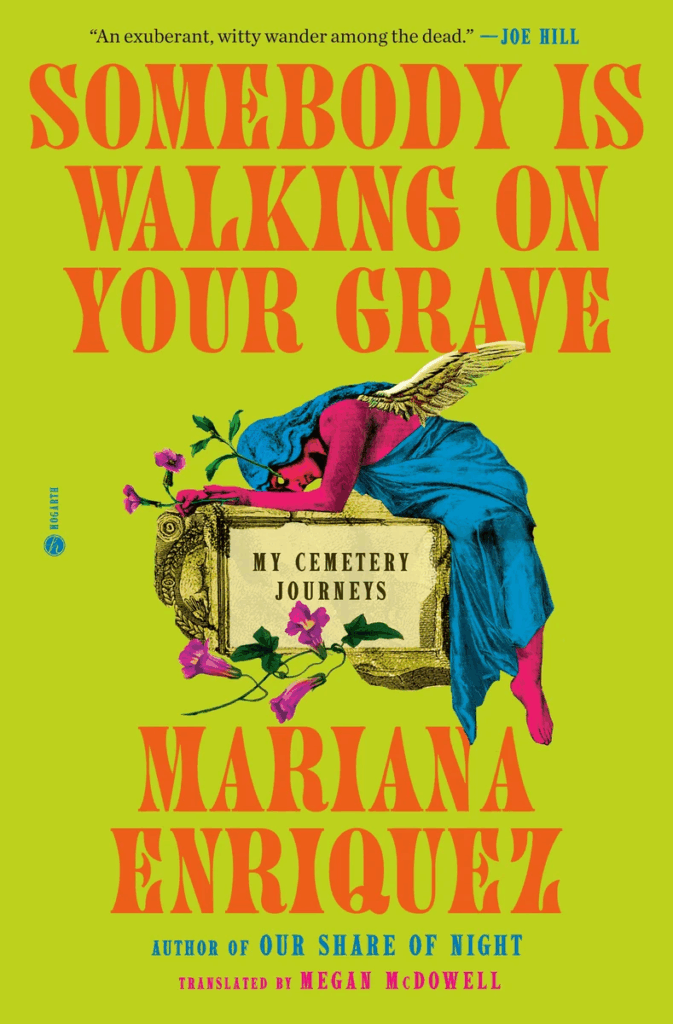

It’s no surprise that Mariana Enriquez, an Argentinian writer well-known for gothic and horror fiction, makes her nonfiction debut with a book about cemeteries. In Somebody is Walking on Your Grave: My Cemetery Journeys (Hogarth; September 2025), Enriquez takes the reader on a wild and expansive tour across four continents featuring 21 cemeteries. However, this book is not simply a detailing of a macabre goth hobby. It is impressive in scope, at turns a blend of memoir, along with a meditation on how different cultures lay to rest and remember the dead, how a history of a place and people can be told through their cemeteries, and why people become fascinated with the dead.

It’s no surprise that Mariana Enriquez, an Argentinian writer well-known for gothic and horror fiction, makes her nonfiction debut with a book about cemeteries. In Somebody is Walking on Your Grave: My Cemetery Journeys (Hogarth; September 2025), Enriquez takes the reader on a wild and expansive tour across four continents featuring 21 cemeteries. However, this book is not simply a detailing of a macabre goth hobby. It is impressive in scope, at turns a blend of memoir, along with a meditation on how different cultures lay to rest and remember the dead, how a history of a place and people can be told through their cemeteries, and why people become fascinated with the dead.

I scooped this book up immediately because, whenever I travel, I also seek out cemeteries to visit, and there are a couple I think about often. The first was a tiny, unmarked cemetery in a small North Yorkshire village, which truly spooked me as I strolled down its paths even in broad daylight. Then, Rosemary Cemetery, a small historical graveyard located in a CVS parking lot in Naples, Florida, is in such an unusual place that it had me digging for the history of who was buried there and why. Enriquez captures both feelings well in her book—the supernatural and creepy feeling of being in a cemetery, as well as its ability to convey history and the details of individual lives lost over time.

Enriquez provides extensive physical descriptions of the cemeteries, accompanied by photographs taken at each location across Europe, the United States, and South America. Particularly fascinating are the details of all the different funerary sculptures that accompany graves, including ones of death embracing the dying, a mother holding the empty clothes of her child, and two giant hands emerging from the ground to grab the statue of a child who was murdered. She painstakingly details how the dead are buried and why they are in that particular cemetery. There’s the New Orleans cemetery, where everyone is buried above ground due to the city’s history of flooding. Additionally, in some cultures, remains are removed and cremated or relocated in the vault to make room for the newly deceased, and there are even a few people buried standing up. Or the unique way people remember their dead children, an unfathomable loss, like in Main Cemetery in Frankfurt, Germany:

It looks more like a memorial than anything else; at least, I don’t see any gravestones. It’s in a corner watched over by the statue of a grieving mother on a bench, and, on the wall, hanging from the trees, and scattered over the ground, there are pendants of plants and sea animals, white hearts inscribed with names like Alexander or Anita, toy balls and cars, pillows, rattles . . . a cemetery of baby objects, branches decorated with colored ribbons and photos like Christmas ornaments.

The why that Enriquez lays out becomes a concise yet detailed examination of the place’s history, encompassing both spiritual beliefs and political history. There are many victims of plagues, indigenous people murdered by colonists, poor people dumped in mass graves, and those dead from wars. The common graves, the shared graves, often also tell stories that are not well known or forgotten.

Near Faraday there is a common grave. How many are there in all of Highgate? Probably a lot, like in all the world’s cemeteries. The one near Faraday is an all-girls grave. Ten of them are buried there, all under the age of twenty. Most of them are teenage prostitutes, girls who’d been lured from the country with promises of jobs as cooks or maids and, once in the city, were brought to filthy brothels instead.

Throughout the book, she thrills the reader with stories of hauntings, feelings of strangeness, and old lore associated with the cemeteries, including her own superstitions. Towards the end, in one harrowing and morbid chapter on Enriquez’s visit to the Paris Catacombs and the remains of Holy Innocents’ Cemetery, she cannot let go of her obsession with this particular cemetery and decides to steal a bone. She successfully brings it home (and names the bone Francois). It is alarming to see someone who has painfully detailed the history of these sites, including acts of vandalism, remove a bone from a historical site. But sometimes it becomes impossible to let go of an obsession, and she seems to do it because she believes the dead are lonely, that she can provide some comfort to the dead person’s soul in removing it.

In the end, Enriquez turns her eye towards grieving and the importance of putting a loved one’s remains to rest when she details the burial of her friend’s mother, who disappeared during Argentina’s dictatorship and whose remains were finally found 30 years later. When we lose a loved one, all we have left is memory, and sometimes having a place where we know they are laid to rest helps us remember and brings comfort. At the memorial service, a person says now that her remains have been found, there’s a place that people can go to read her epitaph. “Where the name and date remain, a voice that says: I was here, now I’m gone. Maybe no one knows my name anymore, but someday someone will remember me.”

Somebody is Walking on Your Grave is compelling reading. As Enriquez reminds us in every chapter, cemeteries fascinate us because it is what we will all become: “We are all, more or less always, walking over a greater or lesser number of dead. There are many more dead people than living; it’s a simple truth: we all end up turned into earth.”’ She also provides us with an extra reason to care, serving as a way to learn about and remember our past.

Emily Webber is a reader of all the things hiding out in South Florida with her husband and son. A writer of criticism, fiction, and nonfiction, her work has appeared in The Rumpus, the Ploughshares Blog, The Writer, Five Points, Necessary Fiction, and elsewhere. She’s the author of a chapbook of flash fiction, Macerated. Read more at emilyannwebber.com.

Emily Webber is a reader of all the things hiding out in South Florida with her husband and son. A writer of criticism, fiction, and nonfiction, her work has appeared in The Rumpus, the Ploughshares Blog, The Writer, Five Points, Necessary Fiction, and elsewhere. She’s the author of a chapbook of flash fiction, Macerated. Read more at emilyannwebber.com.