Interviewed by Hillary Moses Mohaupt

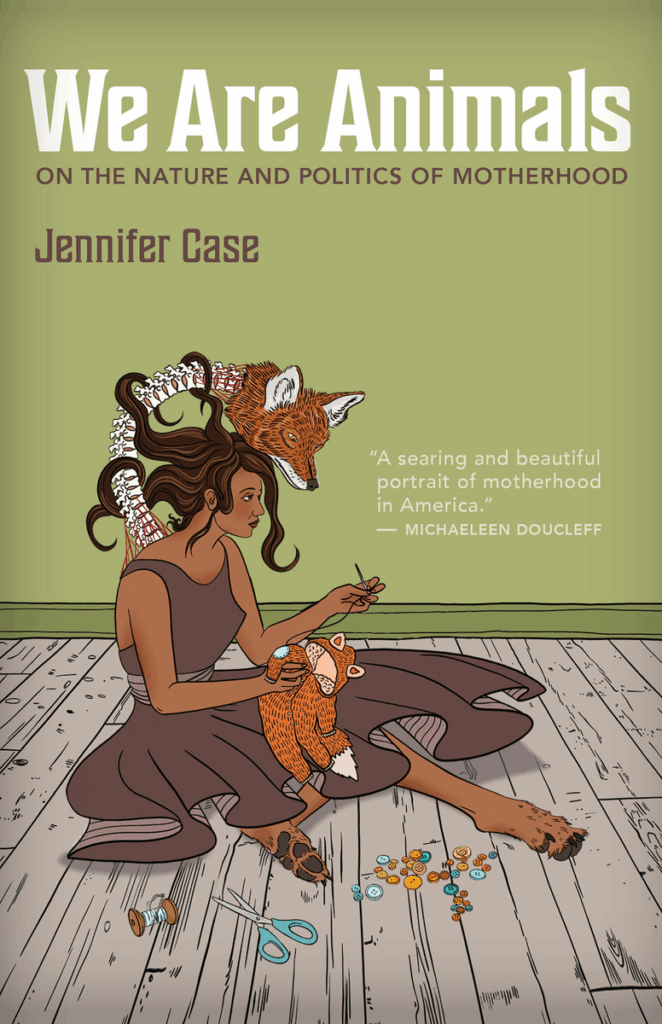

Jennifer Case is an environmental writer, editor and creative writing at the University of Central Arkansas, and she’s also a mother. In her book, We Are Animals: On the Nature and Politics of Motherhood (Trinity University Press; 2024), Case explores the many ways that mothers might lose control, especially in early motherhood – and the ways they can exert some control in a period of life that feels, for some mothers, uncontrollable.

Written during and in the aftermath of her second pregnancy, We Are Animals unpacks the ways that early motherhood has been written about, argued over, legislated, idealized, and regulated by other people for centuries. Case expertly weaves the experiences of other animals into this collection of essays so that mothers – and anyone interested in the plight of mothers – might draw inspiration and strength from the natural world.

I spoke to her from her home in central Arkansas. This interview has been edited for length.

Hillary Moses Mohaupt: First thank you for this book! I was struck by how timely your book is, and how timeless it is. Your kids are eight and twelve now, so early motherhood, the main focus of this book, is behind you. Can you tell me how the book came together, and why this seemed like the right moment to write it?

Jennifer Case: I’m really glad that it comes off as timely and timeless, and that it captures that balance. I do think a lot of the essays are about motherhood in a time-less way, and hopefully they will resonate with people no matter when they become—or became—mothers.

But I also wrote the majority of the essays in response to my second pregnancy, which was an unintended pregnancy in 2016, right as Trump was elected. And at that particular moment, reproductive justice had some setbacks, and in my personal life I was experiencing this loss of control at the same time that women across the nation were experiencing a loss of rights that they had previously had. The personal and the political overlapped so much that it raised a lot of questions for me, questions that I’d never had to grapple with as an individual, but suddenly here they were. And the book offered a way to unpack all of that, explore it.

HMM: Speaking of the timeliness and timelessness, I was just thinking about how you wrote back in 2016, and here we are, nine years later, experiencing a Trump presidency again and experiencing that loss of control again. Do you think that context is part of why the book feels so relevant?

JC: Absolutely. I started sending this manuscript in 2020. It took a couple of years, and there was this moment after Biden was elected, when I thought, “Maybe it doesn’t matter anymore. Maybe they are no longer timely essays.” But, alas, in many ways they reflect our current conversations about motherhood and reproductive justice, just as much as they did in 2016 and 2017 when I wrote them.

HMM: I really appreciated how you wrote towards the end of the book, “I realized that as much as I loved being there, participating in what I believed was my evolutionary, animal self, I also wanted to be somewhere else—and I didn’t know what to do with that tension.” Aside from writing these essays, how have you grappled with that tension differently over time as a writer?

JC: Since writing these essays I’ve come to understand how seasonal creativity and creative practice can be, and I’ve accepted that more than when I was an early mother and younger. There are moments in life when we have a lot of time when we can devote large chunks of time to creative practice, and there’s also time when we’re germinating ideas. So we might not be writing as much, but we’re still thinking, or, in my case, during the pandemic, when I had kids home with me all day, I did not do any writing. I cooked creative meals and I gardened, and those were my creative practices for a season of life. So I’ve come to be more flexible, understanding of those seasons and patterns.

Looking at this book now though, I recognize how tense early motherhood can be, because early motherhood is so demanding in terms of time. You’re often sleep deprived, and children require a lot of you. And now my kids are 8 and 12 and they come home from school and my son’s outside playing with neighbors and my daughter’s reading a book, and I suddenly have a couple of hours for thinking, where they don’t need me. And that’s delicious and not something I would have predicted when I was writing a lot of these essays. Throughout my life, if I don’t have time to devote to a creative practice, I feel that loss very viscerally. I think it’s important for people with artistic temperaments to find ways to nurture that, even in the small ways you can when you have a lot of other expectations and responsibilities.

HMM: This is sort of a tangential question to the book, but are you writing about how motherhood looks different now, now that you have more time to breathe and think?

JC: I haven’t but that’s interesting. That would be an interesting thing to explore.

HMM: It would give other writers some hope. Things will eventually get better.

JC: They will, they will.

HMM: I really appreciated that throughout the book you address those hopeless moments, especially in the first weeks, when you’re like, when was the last time that I slept longer than two hours in a row? For so long, talking about the difficult parts of being a mother, and being a woman, have been considered taboo. Why do you think that is?

JC: I wish I knew.

HMM: It’s like the million dollar question.

JC: I think culturally, there’s such strong messaging about what the ideal mother is supposed to be or look like. I don’t know if it’s because our culture right now is so individualist and focused on individual families rather than the communal experience, but we put so much pressure on mothers. Then we have religious icons. Having grown up Catholic, I grew up with the Virgin Mary as the icon of perfect motherhood and something that mothers were supposed to strive for.

Even though it was impossible to actually become that person, we judge mothers for the moments when they can’t meet those ideals. I don’t know why that judgement is so strong right now, and why there are so many strong idealistic icons of mothers across cultures, and yet there are. And that creates an environment where mothers can struggle—I certainly did, trying to understand who I was and what it meant to be a mother, and the ways in which I was not failing my children even if I did fail to meet these very specific cultural ideals and messages that I’d grown up with and were around me.

HMM: Did writing about the experience of becoming a mother, and especially during your second, unintended pregnancy, help you grapple with it?

JC: Absolutely. When I look at this book, it’s a book about seeing those cultural messages and then dismantling them, trying to uncover what motherhood might be, separate from all of those ideals and messages, and to reclaim it. And writing these essays really did help me see those cultural messages that I was responding to without being conscious of it—and yet judging myself without realizing why I was judging myself. It definitely helped me identify and grow a healthier relationship with myself as a mother and with those messages.

HMM: Are you surprised to have written so many essays, this whole book, about motherhood?

JC: I think so. I was trained as an environmental writer. That’s what I wanted to be. Motherhood just kind of came at me sideways. Once I became a mother I suddenly had all of these questions about motherhood, and found I couldn’t write about other topics. I needed to tackle the questions I had about motherhood, through the lenses that I used in the book.

HMM: I loved how you explored power and privilege and control throughout this book. How did putting together these essays shape how you think about and write about control and privilege?

JC: The book as a whole offered a space for me to untangle what it means to have control or choice, especially reproductive control. When I had my children, especially my second, the different ways we have—or should have—control or choice, got all knotted together. We often think of control or choice as an opportunity for empowerment and autonomy, but then what happens when you lose control or choice, especially when that loss is being imposed on you by a government or social institutions? And then there are also moments in life where we will just never have control, right? Life is always going to give us unexpected challenges. Believing that we can always have choice and control over the direction our life takes—that’s just never going to happen, and we’re going to suffer a lot if we believe that it will. And yet there are also moments in life where giving up control is a kind of submission that’s empowering. I saw that in my experience of childbirth.

And yet I couldn’t separate these ideas of choice and control, and I needed to understand where my experience of motherhood was empowering, where was it disempowering, where had I had choice, where had I lost that choice—and how did it help me better understand how sometimes to let go of control would be more healthy than trying to cling to it. So the book gave me an opportunity to explore and hopefully draw these questions out for others to understand as well.

HMM: I think you definitely accomplished that, as least for me as a reader. You used the image of the knot—you were untangling a knot but it wasn’t entirely loosened at the end, but you can see the different threads that are there and may never come undone. Shifting gears a little bit, one of the essays is about searching for community online, and this need for community is threaded through the book. I appreciate that you write about how online and other communities are sometimes really life-giving, and other times anxiety producing. What was the phrase for people who go to parks —

JC: Stroller stalking!

HMM: Yes! I loved learning that that was an actual thing that new mothers do to connect with other new moms. Where do you seek out community with other mothers and other writers?

JC: For me, since I’d gone to grad school before I went to grad school, I had a community of writers already. Once I became a mother, it wasn’t the community of writers that I lacked, it was a community of mothers, and that was more difficult to establish or find, especially working in academia where people tend to move around a lot.

I’ve lived in central Arkansas for over ten years now so slowly I’ve been able to build that community with other parents through daycares, other parents who work at the university, kids birthday parties, volunteering around the community. And now I’m at a point where I’m trying to grow that community of writers again. One of the gifts of having this book out is being able to connect with other writers who have written about motherhood in the last year or two, and that’s been really lovely.

HMM: I love that. It’s hard to figure out how to connect with other writers in a way that’s going to serve you in the moment.

JC: Yeah, and when I had my kids a lot of my writing network was made of writers at the same stage in their career as me, but many of them didn’t have kids yet, so there was this disconnect at that time, so I couldn’t rely on the same community to serve both needs. Finding ways to grow your communities and networks the way you need to—I think it’s just an ongoing task of adulthood, but it can be hard.

HMM: Yes! It is an ongoing task! So, now I want to talk about the forms different forms the essays took. I loved that some had a very narrative form, others played on other forms. Can you share a little bit about how one or two of them took the form they did? Do you experiment with form? What inspires you to do so?

JC: That was a purposeful part of the project for me, actually. I wanted to use this collection to push myself as a writer and learn how to develop essays in forms that I hadn’t had a lot of experience with. So it gave me an opportunity to experiment with new ways to approach writing creative nonfiction. Some of the content was pretty heavy, and yet I found that if I could continually experiment with new ways of writing the essay, it made the process feel playful and fun, even if it also required me to delve into memories that were sometimes heavy to sit with.

Two of the essays that come to mind immediately when you ask that question: The first one is “A Cost Accounting of Birth,” which was my attempt at an abecedarian. So, A, B, C—the form goes through the alphabet. This wasn’t quite an abecedarian because I don’t have an A or a Z or a Y, and there are two Ds, for instance, so I had to shift that pattern to let the essay be what it wanted to be, but that was a fun one to write because I had all of this research about evolutionary biology, and I always wanted to do an abecedarian. I really enjoyed seeing what that form would let me do with the material.

And the other one is the last essay, which is called “Additional Thoughts on Control.” That one’s inspired by John Paul Lederach called “Advent Manifesto.” He calls it a “Wittgensteinian essay” and his essay is a hundred short fragments and are numbered. My essay isn’t numbered, but I thought what he did with that form was really beautiful. I had all of these lines and images that I wanted to put into the book about control, but I didn’t know how to do it. So I thought, “I’m going to see what I can do with this form.” It was a lot of fun to play.

HMM: I noticed that there were some experiences that you wrote about again and again, but because they were in different forms or from different perspectives, you were really able to explore the emotional complexity of those experiences. It was really powerful.

JC: For me it helped, as a practitioner, it was useful to explore what different forms can do for an essay. And for readers, it’s a book about early motherhood, and yet there’s enough variety in forms that it doesn’t feel like it’s becoming redundant. So it keeps the subject matter fresh.

HMM: It’s very textured, there are multiple layers. So many of the essays were published elsewhere first, right?

JC: Yes.

HMM: Did you have to, or choose to, do any significant edits to any of the essays in putting together this book?

JC: I didn’t, actually. My editor had a couple of comments here and there for clarification. The only significant revision that the editor suggested was to change the order of one essay. In the manuscript I had submitted, I had the essay “Message for the Animal Mother” at the very end because it was the last essay I wrote, and she said, “No, I think we need to move this up and let it be a prologue.” And that made immediate sense to me.

HMM: It immediately gets at many of the themes you tackle. So, once you have something to be read by someone, who is your first reader?

JC: I’m a pretty private person, actually, so I’m pretty slow to share work with others. I usually go through one to two revisions where I’m the only reader. But then once it gets to the point where I really need another person’s feedback or a sense of whether what I’m trying to do with an essay is working, I have two to three writing friends that I’ve been exchanging work with for a while, and I’ll choose one of them based on their availability, and see if they’re willing to take a look. So, yeah, I hold things close for a while and then slowly share it. I’m not someone who shares early drafts quickly.

HMM: Is there anything else I have asked you about that you’ll like to talk about or share?

JC: One of the things that I thought about a lot with this book is audience. I think people often assume that something about early motherhood in particular will only be of interest to mothers or women. As I was writing the book, I didn’t think of the audience as only women or only mothers. I wanted the essays to have the capacity to engage and compel readers who might choose never to become mothers, or men, or young adults, or older adults, and to frame motherhood and the issues and policies that affect motherhood as an issue that affects us all. That was a goal of mine from the start. My hope is that it can reach a broad audience, and the writing and the different forms of essays can compel more than just mothers—though I know it will especially speak to mothers with young children, and that’s also a wonderful thing.

Hillary Moses Mohaupt’s work has been published in Barrelhouse, Brevity, Lady Science, Dogwood, The Rupture, Split/Lip, The Journal of the History of Biology, and elsewhere. She lives in Delaware with her family.

Hillary Moses Mohaupt’s work has been published in Barrelhouse, Brevity, Lady Science, Dogwood, The Rupture, Split/Lip, The Journal of the History of Biology, and elsewhere. She lives in Delaware with her family.