Reviewed by Dorothy Rice

This third memoir from Jeannie Vanasco mines complex, puzzling and all-too-common emotional terrain — a family member or loved one who repeatedly resorts to “punitive silence” rather than express uncomfortable feelings.

This third memoir from Jeannie Vanasco mines complex, puzzling and all-too-common emotional terrain — a family member or loved one who repeatedly resorts to “punitive silence” rather than express uncomfortable feelings.

It’s a particularly cruel and lonely form of punishment. The victim, the person on the receiving end, is powerless to “fix” or work on resolving whatever the problem or issue is. There’s no talking it out. And there’s generally no knowing what triggered the cone of silence to descend.

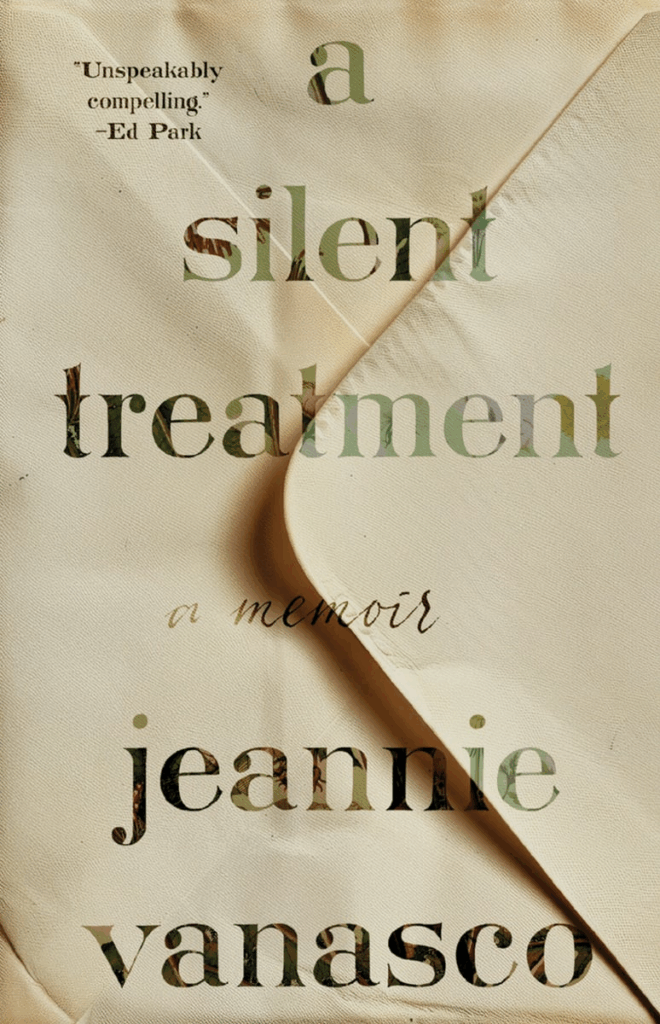

Reading A Silent Treatment: A Memoir (Tin House; Sept. 2025) is an intimate experience. One has the sense of sharing a friend’s thoughts and questions as she struggles to cope with and make sense of her mother’s silence. There’s pain, guilt and confusion caused by the silent treatment, and lingering anxiety over when it will happen again. And, in the midst of an episode, the narrator wonders when, or if, it will ever end — when the ice will thaw enough that words can be safely exchanged, and the relationship re-established.

Vanasco writes, “My mom’s silences — a few days here, almost six months there, over the five years since she moved in with Chris and me — amount to a year and a half, at least.”

It would be easy to conclude that this is an abusive, unhealthy mother-daughter relationship, one the narrator should consider distancing herself from. But in life, and particularly within families, the equation is rarely so straight-forward. There is clearly love and care here, on both sides, and history — between mother and daughter and further back (into the mother’s terribly abusive childhood), all of which provide context for how and why communication devolved in this hurtful way. Despite the unpredictable, periodic silent treatment, and the mother’s occasional cruel insults, they appear to share a deep commitment — if unspoken — to weather these interludes. We learn that before moving in with them, Vanasco and her mother were close; they spoke nearly daily, and wrote long, newsy letters to one another. The silent treatment is not what she experienced growing up. At least it wasn’t directed towards her. Vanasco writes:

She never did this to me when I was a child, not that I recall.

She did it to my dad though. They used the silent treatment on each other, she explained, because they didn’t want to say something they’d regret.

What does she want to say now that she’d regret?

The memoir is part chronology, charting the grueling, soul-crushing day-after-day cycle of a particular “silent treatment” that, in the midst of it, feels as if it might go on forever. Other segments find the author querying Google, reading research papers and seeking out experts on the topic. She grapples with how to write A Silent Treatment while living it and worries how her mother will react to the book. At times, the venture seems too fraught. The writing process slows and stutters before finding a path forward. She commiserates with friends who also have difficult relationships with their parents.

There is plenty of humor too, cats to pet and an understanding partner to share the experience of being shut out with. Googling national days (after learning it’s National Chocolate Parfait Day) Vanasco considers proposing the addition of a “National Silent Treatment Awareness Day.” The website asks for the “story” or rationale. Here’s part of her response, “A psychology study reported that 75 percent of Americans had received the silent treatment from loved ones, and 67 percent had inflicted it on loved ones.”

It’s one study, and the percentage may seem high. Yet I’m not surprised by the numbers. After their divorce, my mother confided that Dad often went for days, weeks, up to six months, without speaking to her. I remember my childhood home as “quiet.” Our mother would put a finger to her lips and admonish us not to make any noise, because Dad needed to “concentrate.” We were always in stocking feet. Not to keep the floors clean but because shoes make too much racket. I don’t remember speaking to him and not being responded to. But then, he wasn’t the kind of Dad you initiated a conversation with, and we kids weren’t the target of his silence. At the dinner table, he would repeat old chestnuts, like, “If you don’t have something nice to say, don’t say anything,” and “Children are meant to be seen and not heard.”

When I was the direct victim of punitive silence — as my second marriage deteriorated beyond repair — I would count the number of words my husband spoke to me in a day, a week, a month, usually fewer than the fingers on both hands, and all of them transactional. And, like the narrator’s mother, when there were no words, there were brief, impersonal notes left on the kitchen counter — mostly bills to pay. I felt invisible and valueless, guilty too, wondering what I had done that made him so angry.

Silence, refusing to engage, becomes the ultimate way to control the narrative — by quashing it. Imposing silence prevented my mother and I from using our words, our emotions and experience. Silence neutralizes and disempowers, creating an unequal, unhealthy power balance in a relationship.

While chronicling her own experience of living through a particular silent treatment, Vanasco also narrates the difficult process of deciding how to construct this book, then actually writing it. Which, in some ways, was as difficult and painful as the silent treatment itself. Memoir is often fraught with questions of loyalty to family, privacy and perception. The author asks her mother how she feels about having her behavior, her painful, inexplicable silences, written about and shared publicly. The responses are surprising. They add another layer of complexity to the relationship.

The mother is proud of her daughter. She supports her journey and accomplishments as an author. “Write the book you want to write,” her mother says, “It’s your book. I’m not telling you what to write in it.” She says the title is perfect and that she doesn’t want to read it in advance of publication; preferring to read it when everyone else does. Which, naturally, makes the author nervous — what if reading A Silent Treatment triggers another silent treatment?

In the end, they arrive at a better, more comfortable place (I don’t want to give away too many details). They are speaking, enjoying one another’s company. Yet, just as the reasons why the silent treatment descends are many and rarely adequately shared, she can’t know when it will happen again, or, once it does happen, when it will end.

A Silent Treatment provides a moving, emotionally honest picture of how it feels to be the victim of a behavior that becomes entrenched for varying reasons. Regardless of the genesis, withholding and withdrawing, refusing to communicate with anything other than stony silence, becomes a quiet sword. Like living with a disease that goes into remission and then mysteriously reappears, there’s no clear answer or remedy.

A Silent Treatment is a brave, relatable testament to one daughter’s commitment to stay in relationship with her mother, no matter how difficult and painful. And, for those who write memoir and personal narrative, it also serves as an excellent example of how one author answers the question of whether it’s possible to write multiple memoirs. In Vanasco’s case, each is distinct, skillfully, meaningfully excavating different parts, different slices, of a life.

Dorothy Rowena Rice is a writer, freelance editor, managing editor of the nonfiction and arts journal Under the Gum Tree and a board member with the Sacramento area youth literacy nonprofit, 916 Ink. Her published books are The Reluctant Artist (Shanti Arts, 2015) and Gray Is the New Black (Otis Books, 2019). She is the editor of the anthology TWENTY TWENTY: 43 stories from a year like no other (2021, A Stories on Stage Sacramento Anthology). At age sixty, after retiring from a thirty-five-year career in environmental protection and raising five children, Dorothy earned an MFA increative writing, from UC Riverside, Palm Desert. Learn more and find links to many of her published stories, essays, reviews and interviews at www.dorothyriceauthor.com

Dorothy Rowena Rice is a writer, freelance editor, managing editor of the nonfiction and arts journal Under the Gum Tree and a board member with the Sacramento area youth literacy nonprofit, 916 Ink. Her published books are The Reluctant Artist (Shanti Arts, 2015) and Gray Is the New Black (Otis Books, 2019). She is the editor of the anthology TWENTY TWENTY: 43 stories from a year like no other (2021, A Stories on Stage Sacramento Anthology). At age sixty, after retiring from a thirty-five-year career in environmental protection and raising five children, Dorothy earned an MFA increative writing, from UC Riverside, Palm Desert. Learn more and find links to many of her published stories, essays, reviews and interviews at www.dorothyriceauthor.com