Reviewed by Lindsey Pharr

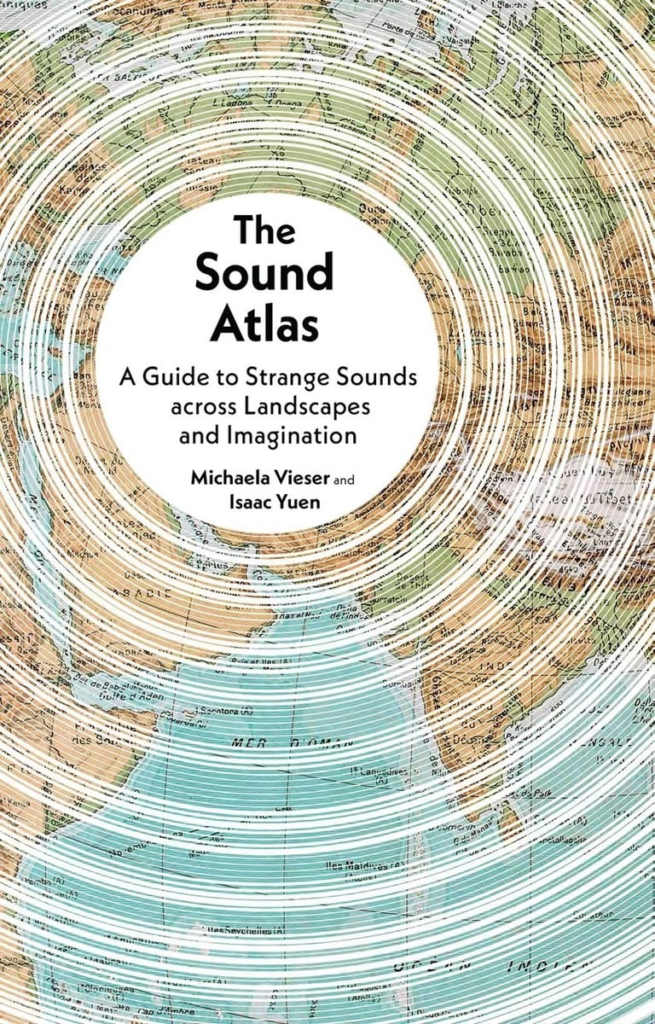

Nature writers Michaela Vieser and Isaac Yuen’s collaboration, The Sound Atlas: A Guide to Strange Sounds Across Landscapes and Imagination (Reaktion Books, 2025), takes the reader on a sonic odyssey that explores the aural terra incognita of our planet and beyond. In a nod to the classical atlas, each chapter begins with the discussed geographical locations listed as subtitles. These locations are often disparate and far-flung. In the gifted hands of these collaborators, each chapter becomes a braided essay that moves seamlessly from location to location to create a unified discussion of real and imagined sound.

Nature writers Michaela Vieser and Isaac Yuen’s collaboration, The Sound Atlas: A Guide to Strange Sounds Across Landscapes and Imagination (Reaktion Books, 2025), takes the reader on a sonic odyssey that explores the aural terra incognita of our planet and beyond. In a nod to the classical atlas, each chapter begins with the discussed geographical locations listed as subtitles. These locations are often disparate and far-flung. In the gifted hands of these collaborators, each chapter becomes a braided essay that moves seamlessly from location to location to create a unified discussion of real and imagined sound.

In their foreword, the authors encourage various approaches to the book: “One way to read it is to heed its title, pinging from location to location like an atlas. Another way is to follow its structure, laid out chronologically, stretching from the first explosions flung across the universe to transmissions humanity has cast out into the far future.” Feeling seen as a chronic page-flipping scene-sampler, I immediately turned to chapters that resonated with my current obsessions: first a later chapter entitled “The Untamable Ritual of Keening,” then back to the earlier “To Be Defined by Sound: Regarding the Cicada,” before starting again at the beginning and reading straight through. I recommend both approaches.

This is a book for the curious, one whose authors seem more than happy for you to set it down and supplement with a bit of impromptu research, as seen in this witty aside that follows a brief passage on the tongue-twisting station announcements of Welsh trains: “But this is not the scope of this particular sound excursion, and so we stop here and ask anyone interested in learning more about this topic to leave this train of thought and find their path in the wilds of the Internet.” Meanwhile, in “the wilds of the Internet,” Michaela Vieser’s website contains a map where locations from The Sound Atlas contain links to select sound samples.

The Sound Atlas accomplishes something that is very difficult to do here in the Anthropocene, in that it successfully navigates the knife-edge of wonder and grief in a rapidly changing world, a world in which our species has built wonders and is also responsible for mass destruction. Each chapter ends on a philosophical note that causes the subject at hand to remain with the reader long after they leave the page. Existential musings such as these reach far beyond, for example, the very niche topic of archaeoacoustics. In “Reconstruction of the Paleosonic: Bringing Back the Sounds of Past Life,” the authors write, “What was said in the final call of the last mammoth, ringing across a realm of fir and whirling snow? Did it trumpet out in vain, in hope for an answer that would never come? And how should we ourselves deal with this process of crossing from presence into absence, towards that looming threshold which we must one day breach?”

The authors’ collective voice⎯a marvel of craft, this one cohesive voice from two writers⎯blends David Attenborough’s pathos with Carl Sagan’s awe and a dash of Werner Herzog’s bleakness. In “The Humility Pipe,” faced with the finicky nature of the delicate instrument, they jokingly posit, “Do harpsichords even like having an audience, one wonders?” Then, in an unflinching look at nuclear weapons entitled “Sounds of the Atomic Age,” the authors move from discussing the studio-made sounds that accompanied film depictions of mushroom clouds to the generations-long suffering that nuclear testing has caused Pacific islanders. In this chilling passage, they write:

“Nuclear fallout makes no sound, can fall as light as pure snow. Before their skins peeled and their bodies grew tumours, the children on Rongelap Atoll in the Marshall Islands played in a never before seen coral ash that drifted down on their shores, the result of Operation Castle Bravo, the 1954 nuclear test at Bikini Atoll…There is a lag between act and admission. There is an even longer lag between culpability and compensation.”

This odyssey is not for the faint-of-heart. I came for the wonder⎯moths scrambling bat sonar to escape predation, mysterious singing stones⎯and stayed for the clear-eyed narration of what it feels like to be a human in this moment, as summed up in the authors’ look at The Voyager Golden Record, “…our salvation will most likely need to come from within. But hope is…sometimes manifested through the making of a message sent out into the void, regardless of the odds, with the noblest of intentions.”

Lindsey Pharr (she/her) lives and writes in the woods outside of Asheville, North Carolina. She received her MFA from the Naslund-Mann Graduate School of Writing. Her work has been published in River Teeth, Southeastern Review, SmokeLong Quarterly, and elsewhere. A full list of her publications may be found on her website: www.lindsey-pharr.com

Lindsey Pharr (she/her) lives and writes in the woods outside of Asheville, North Carolina. She received her MFA from the Naslund-Mann Graduate School of Writing. Her work has been published in River Teeth, Southeastern Review, SmokeLong Quarterly, and elsewhere. A full list of her publications may be found on her website: www.lindsey-pharr.com