Interviewed by Vicki Mayk

I began following Kerry Neville on Facebook more than a decade ago when she took a solo trip to Morocco, announcing it was the start of her reclaimed life. Since then, her social media posts have allowed us to journey with her to Georgia, where she’s now an associate professor at Georgia College & State University, and on multiple trips to Ireland, where she has been a Fulbright Scholar.

I began following Kerry Neville on Facebook more than a decade ago when she took a solo trip to Morocco, announcing it was the start of her reclaimed life. Since then, her social media posts have allowed us to journey with her to Georgia, where she’s now an associate professor at Georgia College & State University, and on multiple trips to Ireland, where she has been a Fulbright Scholar.

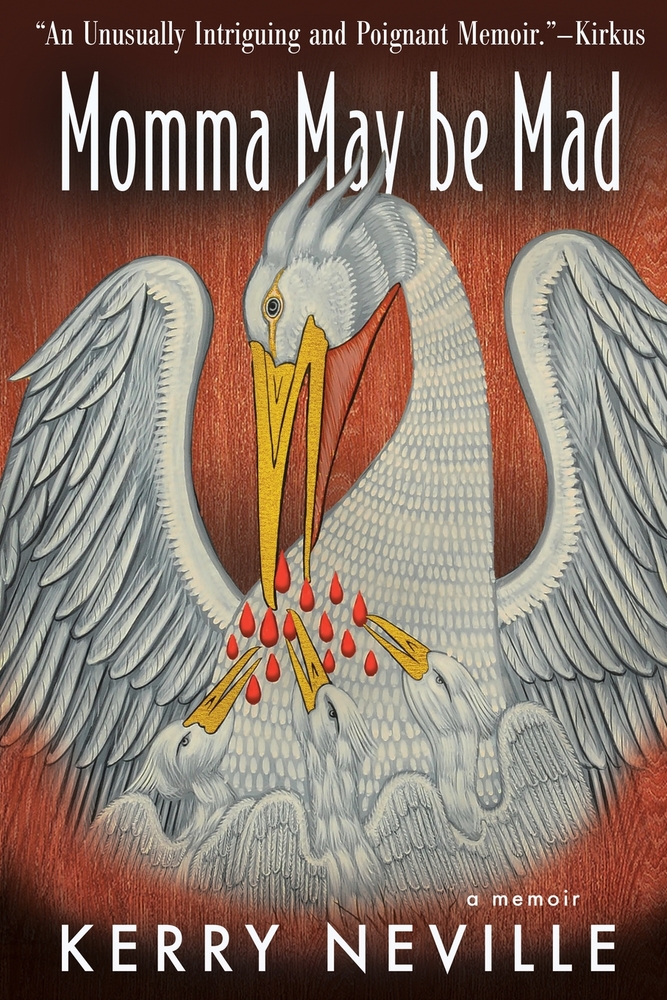

Like most social media posts, hers didn’t tell the whole story. Her new memoir, Momma May Be Mad: A Memoir (Madhouse Publishing; 2025), chronicles her journey back to life after years spent trying to die. Despite losing much of her memory to electric shock therapy, she reconstructs her past with candor, writing in lyrical prose using an inventive, nonlinear structure.

Previously the author of two published short story collections, Neville now tells her own tale in a stunning memoir that is at times difficult to read, but ultimately transcendent. Diagnosed with bipolar disorder, she struggled with alcoholism, anorexia, and self-harm. Multiple hospitalizations and 25 rounds of electric shock therapy did not help her. One day an irresponsible psychiatrist labeled her “hopeless,” and Neville — then the mother of two children — walked out of his office determined to prove him wrong. Following her therapist’s encouragement to “do whatever it takes to have the life you want,” Neville rebuilt her life.

I spoke with Kerry as she prepared to make another trip to Ireland. This interview has been edited for length.

Vicki Mayk: You begin this memoir by asking, “How do you write a memoir when you can’t remember?” You position yourself as an unreliable narrator. Yet I’m impressed with the confidence of your narrative voice. How did you achieve that?

Kerry Neville: One thing that happened after my divorce was that I spent significant time on my own. Over the course of my life, I hadn’t done that before. I grew up with an intact family, so I lived with my parents. I went off to college and had roommates, then a boyfriend. I went to grad school and met my now ex-husband, and we moved in together almost right away (too soon!) and then had children. After divorce, I discovered that I didn’t have to listen to what other people were telling me was important about me or what was wrong about me or wrong about what I was remembering. I could determine what memories or events were the ones that defined who I was. Tomorrow? They might shift. So we are unreliable narrators as each day we reconstitute ourselves with new understandings, priorities, longings, and regrets.

VM: How did you begin to trust yourself to tell the story?

KN: I’m in a 12-step program and the tenets are honesty, open mindedness, and a willingness to get honest with myself. Valuable tenets for writers, especially of creative nonfiction. I learned to trust my understanding no longer muddied by substances or bipolar’s highs and lows. When I’m unsure about factual accuracy? That’s easy to check on. Again, honesty, open mindedness, and willingness to talk to people who lived with me or surrounded me in those times…. We’re not only after the straightforward, factual truth of events as they happened, because that’s just an inert timeline. We all have gaps in our timelines. So I check in with my gut, brain, heart, and trusted long-term friends — mutual memorykeepers—and change or expand what I’m learning about self-in-time-in-the-world as I’m writing… Over time in the rewriting and revising, I gained clarity: a more incisive and perhaps generous-to-all emotional truth.

VM: While we’re talking about emotional truth, I was really impressed with the way you treated your relationship with your ex-husband. It would have been natural to be angry about some things that happened when your marriage ended, but I found your treatment of him so balanced. How did you manage to achieve that?

KN: A relief and a gift to hear you say that! I gave the manuscript to people who knew both of us during those times, and I said, ‘Please read it and flag anything that seems like I’m not extending empathetic understanding toward him of what it must have been like living with me.’ What if the tables had been turned and I had a partner who was actively trying to die for so many years? I don’t know if I would have had the fortitude to stay. For whatever happened in the end, for many years, he did try to keep me alive, and our family together. My kids read the book before publication and gave me the green light because they saw that I wasn’t trying to justify myself or assign blame. Writing creative nonfiction requires circumnavigating the prism: we try to see as many facets, angles, reflections and refractions as possible.

VM: You chose a structure that accommodates gaps in memory. It’s episodic and nonlinear. I especially love the device you used: push pins to mark dates and moments. How did you come up with that idea?

KN: If you could see my board behind my computer—pushpins with notes on top of notes on top of notes. A collage whose only order is the one that I’ve given it…today. Photographs, printouts, lists, photos – all movable. Pull one out and pin it somewhere else, rearrange for suggestion, association, and meaning. As I mentioned earlier: Every day we rearrange the importance of past events and memories in different ascending or descending order of importance. It’s how memory works. Something was there, and maybe we can’t fully access it, but we get a flash of that something. I also kept thinking about the actual pinning and its connection to self-harm (in my story). Pins pierce and leave their marks.

VM: In this memoir you’ve created an intimacy between yourself and the reader, in part because of your honesty in telling your story, but also in the way you speak to the reader. I love this line: “I am reaching through the page for you, closer, closer still, imagining you beside me now.’ You address us as “dear reader” throughout. In theater, they call that breaking the fourth wall, directly addressing the audience. Why did you choose that kind of direct address?

KN: There’s this assumption that when we’re reading a memoir, that somehow it’s not performance, that it is somehow not premeditated, not filtered like the construction that we bring to writing fiction or writing a poem. But it’s a performance, right? I tell my students, when you write, you are trying to deliberately steer your reader into knowing things and feeling things. We want to have a certain effect. So it’s a curious space for those of us who write creative nonfiction and memoir, that we present ourselves as accessible, as intimately connected to our readers, no dissembling, akin to automatic writing of the 19th century (which of course, was a parlor trick!). It would be disingenuous to say we’re not being deliberate in our authorial directives via language and presentation of scene and thought. Pushpins in the reader. That’s why I break that fourth wall in this book and let the reader know up front, because of what’s happened to my memory from electric shock, that this is a construction. It can’t be anything but that.

VM: My favorite place where you address the reader directly is in the pivotal scene when your awful psychiatrist — who you name “Dr. Disregard” — tells you that you are hopeless. You write “Dear Reader, bookmark! Here now is the turning point.” You got good and pissed off enough to make a change in your life. It’s hard to believe a doctor would say that.

KN: It is really what happened. And I did get good and pissed off… I told friends who are doctors and therapists about that moment, and they said, horrified, “That is so unethical. How could a doctor treating you say that?” Many patients in the mental health care system feel powerless and are willing to believe how other people, authorities, in that system define them. I’m very aware of inequity in the mental health care system. That doctor tried to define me as “hopeless” but what did he know, really, about the me that didn’t “present” in his treatment notes?

VM: You write very eloquently and insightfully about those experiences.

KN: I wrote about my first hospitalization, right after my son was born, and I landed in the hospital. One staff psychiatrist said to me, ‘Why are you here? You’re young, you’re pretty, you have a PhD, you’re successful. Why are you here?’ They tried to get me out of there. They told me, ‘you don’t belong here with these people.’ But at that moment? I didn’t belong anywhere else but there. I needed help. And by “these people,” he meant fellow patients who were not white/educated/employed. And I know that because I am white/educated/employed, I was given grace, leeway, and special considerations in the mental health care system because of this.

VM: In your book, you’re not just telling your story: you inform it by bringing in all kinds of other material. You’re sharing the etymology of words. You’re bringing in pieces of history. You quote Thomas Merton. When you write about messaging your children when you’re separated from them, you reference the history of wireless communication. My favorite was the story that you return to again and again about Captain Scott’s disastrous Antarctic Expedition. What’s the value of bringing in those references?

KN: I’m a very curious person. I love learning about…everything! What I’m interested in outside of myself also tells me who I am. But the larger idea for the book? I was trying to reconstruct, in the infinitude of a millisecond, all that I am and all that brought me to the moment of writing this understanding, this version. What would that look like? Hopefully this book. This book tries to emulate that infinitude of a millisecond (obviously can’t be read in a millisecond). A flash of understanding — what makes us who we are right now — memories, yes, but books we’ve read, prayers we say, ephemera collected on the mind’s dusty bookshelves.

VM: Your prose also reflects your inner life. The language is beautiful throughout. But when you move out of the dark times in your life, the writing becomes even more lyrical. The nature imagery is such a marked part of your prose in the second half of your book when you are recovering.

KN: Yes, Persephone emerges from the dark underground into spring, lusty and hungry. That’s what happened to me. When the annihilating dark lifted, I suddenly and urgently felt 3-D/HiDef connected to the world. I notice details and I pay attention, because I’m trying to remember, to store things up because I have forgotten so much. When memories are stripped away, as by electric shock, and then you survive that decimation and come back to life? I said to myself, “Okay, I’m coming up from underground. Naked. Now, what do I want to put back on? What am I going to surround myself with? Where will I focus my love and attention and passion?” For me? Loam, sky, birds, trees, horses — what is alive with me.

VM: Your memoir ends with you in a good place, with a reclaimed life. But you remind us that you’re still dealing with the fact that you have a bipolar brain that tends to go to the darkness. You remind us that it’s still part of your life.

KN: Yes, this is not a “recovery memoir,” but a “recovering” (gerund) memoir. Recovery is not done. It’s never going to be done. The 12-step program tenet: ‘one day at a time,’ right? You can’t guarantee forward self-in-time. None of us can guarantee anything, really. I think in this sub-genre of memoir, it would be false to just say it’s only ascending light, there are shadows and I’ve learned to live with those.

Vicki Mayk

ReviewerVicki Mayk is a memoirist, nonfiction writer and magazine editor who has enjoyed a 40-year career in journalism and public relations. Her nonfiction book, Growing Up On the Gridiron: Football, Friendship, and the Tragic Life of Owen Thomas (Beacon Press) was published in September 2020. Her creative nonfiction has been published in Hippocampus Magazine, Literary Mama, The Manifest-Station and in the anthology Air, published by Books by Hippocampus. She’s been the editor of three university magazines, most recently at Wilkes University in Wilkes-Barre, Pa., and now freelances and teaches adult writing workshops. Vicki previously served as reviews editor at Hippocampus Magazine. Connect with her at vickimayk.com.