Interviewed by Jenny Bartoy

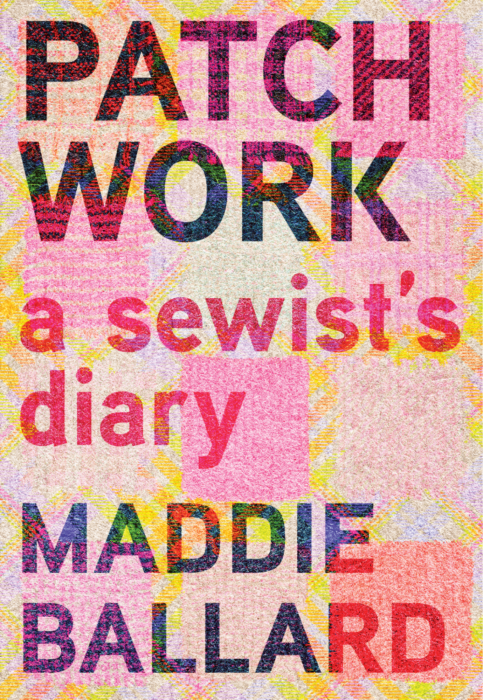

Patchwork: A Sewist’s Diary (Tin House; 2025) is Maddie Ballard’s debut memoir, a collection of essays structured around the making of seventeen garments. Precise, charming, and lyrical, the book explores Ballard’s practice of the sewing craft from novice to maven, alongside the ups and downs of her twenty-something life.

Patchwork: A Sewist’s Diary (Tin House; 2025) is Maddie Ballard’s debut memoir, a collection of essays structured around the making of seventeen garments. Precise, charming, and lyrical, the book explores Ballard’s practice of the sewing craft from novice to maven, alongside the ups and downs of her twenty-something life.

Ballard touches on topics both concrete, such as stitching and cooking in delightfully sensory writing, and political, investigating the ways in which sewing intersects with feminism, environmentalism, capitalism, body image, and more. In a culture determined to distract us with increasingly fast-paced and artificial content, Patchwork is a wondrous ode to making, inviting the reader to slow down and ponder the value of crafting by hand.

I had the pleasure of chatting with Ballard via Zoom, bridging the time zones between her home in Melbourne, Australia, and mine in Tacoma, Washington. We spoke about her approach to writing this book, the discoveries she made on her sewing journey, and the cautious hope she hopes to impart on her readers.

Jenny Bartoy: I so enjoyed reading Patchwork. It made me antsy to dust off my sewing machine but also provoked a thoughtful meditation on the meaning to be found in textile crafts. Starting broadly, how did the idea for this book come to you?

Maddie Ballard: It sort of happened by accident. Three years ago, I had written the essay about making a coat after my breakup for my Substack, and when I published it, I got this really nice response. Lots of people wrote to me to say that they liked it, who weren’t necessarily themselves into sewing, which I thought was quite interesting. And so I wondered whether I might have more garments I might want to write about, but I didn’t really give it any serious thought. And then the Emma press, which is the UK publisher of Patchwork, put out a call for book proposals, and I wrote a short proposal [where] I spitballed some ideas for what the subjects of the chapters might be, and sent it off with another thought.

Nine months passed, I didn’t hear anything, and then they got back in touch, and they were like, “We really like the sound of your book. Could you send us the full manuscript?” and I hadn’t written any of it! I wrote it in a burst of energy in 2022 and 2023 and it is a record of my sewing up to that point. It came about quite organically, and I found it a really fun project. I really wanted to write something about sewing that wasn’t instructional. I felt like there were a lot of books about how to sew, and those are important resources, but there was this whole other emotional side of it that wasn’t being touched on.

JB: Speaking of the emotional side of thing, your story opens against the backdrop of COVID-19 and lockdown and it explores the comfort provided by tangible handwork. How can sewing or other crafts make difficult times easier?

MB: It’s more relevant now than ever. At the time of Covid, it felt like that was the most dramatic and terrible shift that I’d ever seen in my lifetime on a large scale, but I feel like things are arguably worse now. In times when things feel unstable, it’s quite useful to have something that’s both very concrete and very controllable to handle. There’s a lot of reassurance in knowing that. It sounds really small, but you have control over one seam, and then eventually that will turn into a garment, and you’ll have this thing that you’ve made that you can touch and hold. And it has a practical use, but it’s also something that’s quite beautiful. Crafts occupy this unique space between being practical and also artistic, and that’s very comforting to me.

JB: On the first page, you introduced this book as “a love story,” and I read it as both a love story with sewing and a love story with the self. Would you agree?

MB: No one’s asked me that before! I definitely didn’t plan it [that way]. I’d started writing about sewing because there was an end of a long-term relationship. I was very conscious of not wanting to write a breakup narrative, but I felt like it was important to honor that in some way. So I wanted it to be in the book.

Then in the years that unfolded after that relationship, I came to understand myself in a different way, and to feel at ease in myself in a way that I couldn’t have anticipated. And I do think sewing was a big part of it. It’s not that often in your adult life that you have to be bad at something. It’s very possible once you’re “grown up” to only ever do things that you’re already good at and to pursue the skills that you’ve already built or the interests that you already have.

But with sewing, I was already 25 by the time I started, but I was doing this thing that I was initially very bad at. And then I saw myself become better at it [and also come] to terms with my own taste — the things I like, the kind of fabrics I like, the sort of things I want to make, the ideas I have. And because sewing is so slow, having to affirm those decisions to myself over and over during the process of making something [was] a kind of revelatory process. By the end of it, it felt very much like an act of self-love and affirmation.

JB: Discovering your own taste is such a formative experience in making art, and it certainly applies to writing too. You write at one point that the words “text” and “textile” are related, and that writing and sewing are both works of weaving. Can you tell me more about that connection?

MB: [Writing and sewing] both come together in piecemeal ways. You’ll be percolating ideas for something to write for a long time, and then when it comes to fitting it together, you sort of weave the sentences together, and you figure out how the language will work. I think sewing has a similar kind of piecemeal quality. You think about what design you might use, what the pattern is going to be, how you’ll make the adjustments, all of these aspects of the process come together, and then finally you get the finished product.

These two processes are slow and involve many micro decisions, and they’re both tweakable and highly customizable. I really see a connection between them. In sewing, you can see each step for what it is at each point. Whereas in writing, there are lots of steps, and you have a vague sense of what they might be, but they sort of shift the whole time, and there is no map in the same way that there’s a [pattern] when you start sewing something. The decisions that are involved in writing feel quite different in terms of the stakes. It’s way harder to write than it is to sew something. Sewing is something creative I can do that doesn’t necessarily require me to second guess myself at every point. I’m going to end up with something even if it’s flawed, and if it’s terrible, I’ll cut it into something else. Whereas, you could spend six months writing [something] and ultimately you’re not happy with it and you don’t want anyone to ever read it. The two processes are both important parts for me of an artistic practice. I find them necessary complements.

JB: In the book, you discuss a variety of political concerns as they relate to sewing. Textile work has long been a tool of political activism, but in the act of creation itself, one can make a difference. What were some discoveries you made in your sewing journey?

MB: The most revelatory insight I’ve had from the whole sewing process is how much work it takes to make any garment. I had never considered beforehand that every single piece of clothing I’ve ever owned has been made by people. Most people have a general sense that the way their clothing is made is not ethical and that fast fashion is bad — I think that’s a generally accepted truth. But very few people understand how much labor goes into their clothing and under what conditions it’s produced and from what kinds of materials. Once I understood that it takes a lot of time and effort, and that it shouldn’t be a disposable thing, I really wanted to make each decision along the way count a little more.

One of the great things about sewing [is that] there’s a certain power in being able to have a little more control over the sustainability of the garments that you wear each day, and to know that when you make something, you can make it to last, and you can choose a fabric that you know hasn’t been produced from plastic fibers and is not going to shed micro plastics. It’s obviously not something that everybody has the resources to do, because it does take time to sew things and lots of people are time poor. And in some ways, [it feels like] a moot point, because the actions of one individual are not ever going to be enough. Nothing one person could do is ever enough. But questioning the system and [having] an awareness of what the options are, that’s really important. I couldn’t do nothing. A little bit is better than nothing.

JB: I appreciate that you give this nuance when you write, “The opposite of a thoughtless consumer is not a saint, it’s a conscious consumer.” I’m curious how your consumption patterns have changed since you dove into this world of sewing?

MB: I’ve been very lucky in that when I first started sewing, I had a lot of time to sew. I made a lot of things that have lasted a long time since then. I do probably still make the majority of my clothes, but now when I buy a piece, I’m looking for something that I know is going to last, and also for something that I’m still going to like in two years. I’d say my buying taste has skewed towards things that are a little bit more classic, or investing in materials I know are good.

I have also become more of an advocate for second-hand clothing. In many cases, you can’t afford to buy exactly what you would like, but even being able to take a pair of jeans out of circulation for the second time feels like a better decision to me than buying a fast-fashion pair the first time around. That’s something else I’ve become conscious of in terms of buying fabric itself. Going to a fabric store is a delightful, tactile experience, and everyone should do it for fun one day. But now I only buy natural fabrics, and I like to know where they’ve come from, if possible.

JB: On a related note, you write about body image and how sewing forces a confrontation with our bodies and their perceived flaws, due to the particular fit of the clothes being made. How has your thinking evolved in regards to body image since you began to sew?

MB: I’m a lot more conscious now of the whole discourse around body image. I was lucky to be raised with a mother who never made me feel bad about my body, which I think is not the case for everybody. And I also am not a huge social media person, so I’ve escaped the brunt of it in that respect. But, in the way of all women everywhere, I have always been conscious of the way I look, of that mattering in some sense, and being evaluated by everybody unconsciously all the time. And sewing has allowed me to take a little more control over that narrative. I’ve seen that happen for other people as well, particularly for sewers who feel like their body does not fit the norm in some way. That can be quite empowering.

There have been aspects of making my own clothes that have made me feel more at ease in my own body [because] I can make sure it’s comfortable as well as flattering. Clothing can so often feel, for women, like a restriction. And I think the culture of wearing makeup or making your body conform in some way to the beauty ideal can be quite a suppressive force. Wearing clothing should be something expressive, which is kind of the opposite of that, because there’s so much possibility out there for what you might look like and what that might say about you and how that might change day to day. Sewing can allow you to do that in a slightly different way, because you can be comfortable at the same time as wearing exactly what you want.

JB: Throughout the book, you don’t shy from using technical sewing lingo. As a sewist myself, I felt at ease but also found that it gave the writing precision and a rich texture.

MB: One of the things that I loved about sewing when I first started was all of the technical terms. I was like, oh, there’s this whole other language that I don’t know anything about. As someone who likes words anyway, this is a delightful kind of corollary of that whole world. I always appreciate when I read a book and the author has not dumbed it down for a lay person. I wanted people, if they didn’t recognize a word, to look it up. That’s very easy to do these days, so I hoped that people might be intrigued to do that. I also think lots of the sewing words are just really fun! Like, the word “notion,” who thought that was the right word for those things? It’s just delightful. And then there’s the sort of influence that’s brought in from all these different places, like the word “toile,” the fact that that’s in French, and there’s this whole history [to it]. I wanted that [history and culture] to be part of the book.

JB: I find it uniquely immersive when a work of writing has a specific lexicon, and this definitely applies to Patchwork. I wonder if you could discuss how you approached the crafting of this book, both in terms of the independent essays and the memoir as a whole.

MB: Someone asked me at one point, why are there seventeen garments [and essays]? I was like, there’s no reason. That’s how many things I had to say. When I started to plan the book I wanted, I knew there were all these different sub-topics within the world of sewing that I wanted to touch on — things like sustainability, or the concept of zero waste sewing, and body positivity, and developing a taste, and sewing for other people.

Initially I made a big brainstorm of all those topics, then sort of tried to attach garments that I’d made to each of those. And then beyond that, it was about matching the chronology of the book and there being a shape to it. I finished [the book] in early 2023, by which point I’d only been sewing for four years, but I felt like there had already been an arc, or a sweep of events and of development in my sewing as well. I wanted to show that shape. I really love in creative nonfiction when it’s not just about the individual stories or the language that the writer has used, but the sort of gesture that the shape of the work makes overall. I wanted it to have shape, and I wanted it to leave the reader with a particular feeling.

JB: What feeling did you want to leave them with?

MB: In a nutshell, I would say cautious hopefulness. I do think there’s a danger of being too optimistic and of trying to end any narrative with a message of hope, which I always think is a bit flat and not quite right, because I certainly don’t feel hopeful all the time these days. There are so many big, pressing issues that are going to come to bear In the next fifty years. I’m very interested to see how it turns out, but I don’t feel like things are trending in the right direction. So I feel like straightforward hopefulness is not quite right, but I also feel like, to be alive, you have to keep telling yourself that there is hope of some kind. You have to keep trying. You have to keep bringing small bits of delight into your every day. You have to keep searching for meaning and trying to make sense of your life and the lives of people you love. And I wanted there to be a sense of those things in the book. I’ve tried to end it in a hopeful place but also kind of open.

JB: Thank you so much, Maddie, for writing this beautiful book and sharing your love story with sewing.

Jenny Bartoy is a French American writer, developmental editor, and critic. She’s the editor of No Contact: Writers on Estrangement (Catapult, 2026). Her work appears in several anthologies and in publications such as The Boston Globe, The Seattle Times, Under the Gum Tree, Room, Chicago Review of Books, CrimeReads, and The Rumpus, among others. She holds a master’s degree from Columbia University and lives in the Pacific Northwest. You can find her at www.jennybartoy.com or on Instagram at: @jenny.bartoy.