Reviewed by Elizabeth Austin

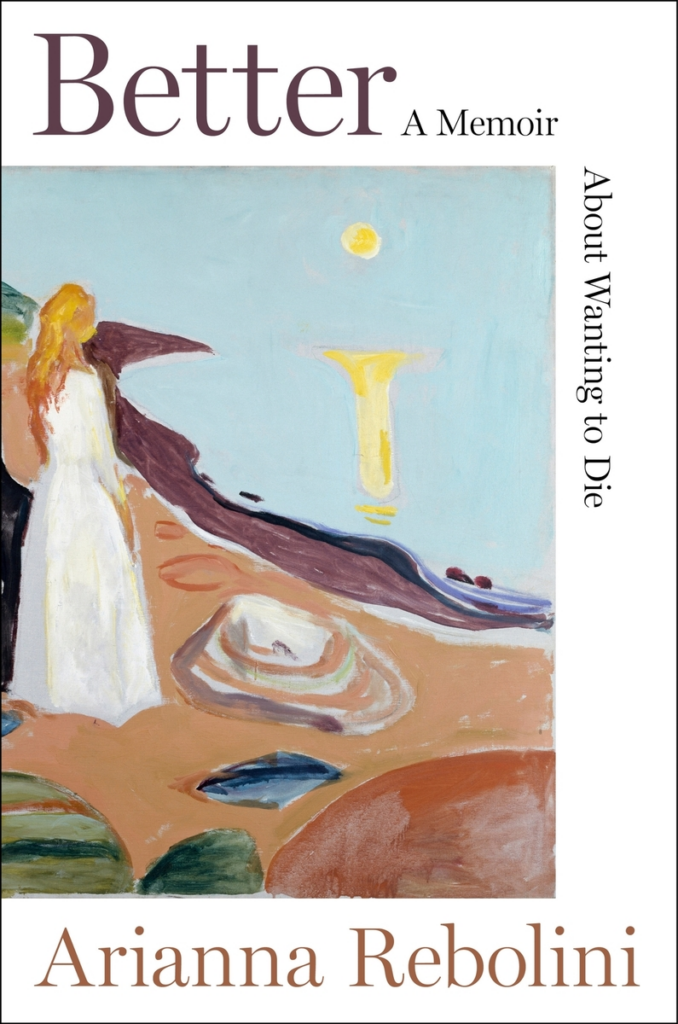

Arianna Rebolini’s Better: A Memoir of Wanting To Die (Harper; April 2025) is an extraordinary hybrid, weaving together confessional narrative, exhaustive research, and cultural analysis.

Arianna Rebolini’s Better: A Memoir of Wanting To Die (Harper; April 2025) is an extraordinary hybrid, weaving together confessional narrative, exhaustive research, and cultural analysis.

Rebolini examines the writings and deaths of famous suicides, critiques the mental healthcare system, explores familial patterns of mental illness, and asks the fundamental question that haunts anyone who’s stood at that precipice: what makes a person want to die?

The structure mirrors the recursive nature of suicidal thinking itself, circling back through decades of her life; from a cry for help in fourth grade with a plastic knife to composing goodbye letters to her husband and son while they slept nearby, after a decade of therapy and living a life that, to people on the outside, seemed to be “better.”

Rebolini writes about suicidal depression with precise clarity. Her descriptions of the interior experience jump off the page and lodge themselves in your chest. She captures the peculiar logic of wanting to die, the way it can coexist with love and responsibility and even moments of joy, the way it lurks like a familiar shadow you’ve learned to live alongside. Better is a welcome intellectual and emotional interrogation of a psychological state our culture desperately wants to pathologize into silence.

I read Better cover to cover in seven hours. I know it was seven hours because I read it sitting in the waiting area of an adolescent psychiatric inpatient facility while my son underwent his intake evaluation for depression and suicidal ideation — psychological struggles he absolutely inherited from me. I hadn’t planned to bring this particular book; that morning, shouldering the heavy emotions of a single parent who finally admitted we couldn’t do it alone anymore, I grabbed a book off the top of my TBR stack without looking. The universe has a dark sense of humor…and impeccable timing.

What Rebolini does brilliantly is integrate cultural context and scholarly examination seamlessly with her personal story. She explores how capitalism’s demands contribute to our collective death drive, how mental healthcare remains inaccessible even for those with insurance (one particularly infuriating passage details her ninety-minute phone call with insurance companies, armed with medical billing codes, just to find out if she could afford treatment), and how depression manifests differently across racial lines. This broader analysis doesn’t distract from the memoir’s emotional core; it enriches it, placing individual suffering within systemic failures that make people want to die.

Sitting in the Philadelphia hospital’s intake room, I watched other parents with their teens. We were all, I thought, trapped in our private hells of inherited pain and parental inadequacy. Better should have felt heavy, suffocating, impossible to read given where I was and why, and my own history of being consumed with feelings of wanting to die. Instead it generated a warmth in my chest — a feeling of solidarity. I felt bolstered by the knowledge that someone else has felt this too, has survived it, has done the excruciating work of examining it rather than hiding it. Rebolini’s memoir became an unexpected companion during one of the loneliest experiences of my life. It was a hand reaching through the dark not to pull me out but to sit beside me and say: I know.

Her exploration of motherhood while managing suicidal ideation is particularly moving. She writes about her decision to have a child despite her mental health history, about the tether her son provides even as she still experiences suicidal thoughts, about the terror of passing down the dark seed of her psychology to him. The vulnerability required to claim motherhood while openly discussing ongoing suicidality, to reject the narrative that you must be “cured” to deserve to parent, is an act of defiant self-definition.

The courage it takes to write honestly about being both a good mother and someone who still sometimes wants to die is exactly what makes this book essential. As a parent grappling with the same fear — that I’ve passed this darkness to my child, that my own struggles have somehow marked them — reading Rebolini’s refusal to be ashamed was its own kind of salvation.

What I admire most is Rebolini’s refusal to offer easy answers or redemptive arcs. She interrogates her own experience with intellectual rigor, poring over the journals and writings of people who completed suicide, trying to understand that fatal moment between wanting to die and doing it When her brother becomes institutionalized, she realizes all her pattern recognition and theories can’t crack the shell of his depression. Better is an acknowledgment that recovery isn’t linear, that getting better doesn’t mean the thoughts disappear forever, and that survival is a practice rather than a destination.

I couldn’t put the book down. Not because of plot — this isn’t that kind of narrative propulsion — but because every page felt like being seen with such clarity that it became its own form of comfort. In that waiting room, facing one of the most frightening days of my parenting life, feeling profoundly alone, Rebolini’s words reminded me that isolation is a lie our shame tells us. Better didn’t make the situation less terrifying, but it sat with me through those seven hours, and that companionship — that literary hand-holding through the dark– was exactly what I needed.

Silence about our darkest impulses only deepens isolation. Dark thoughts grow louder in the echo chamber of shame. Rebolini’s decision to speak plainly about suicidal ideation as an ongoing condition she manages creates space for the rest of us to breathe. This is radical work. By refusing to hide the uncomfortable truth that she can be a loving mother, a successful professional, a person in recovery, and still sometimes want to die, she gives permission for the rest of us to exist in our full, complicated humanity.

Elizabeth Austin’s writing has appeared in Time, Harper’s Bazaar, McSweeney’s, Narratively and others. She is currently working on a memoir about being a bad cancer mom. She lives outside of Philly with her two children and their many pets. Find her at writingelizabeth.com and on Instagram @writingelizabeth

Elizabeth Austin’s writing has appeared in Time, Harper’s Bazaar, McSweeney’s, Narratively and others. She is currently working on a memoir about being a bad cancer mom. She lives outside of Philly with her two children and their many pets. Find her at writingelizabeth.com and on Instagram @writingelizabeth