Reviewed by August Owens Grimm

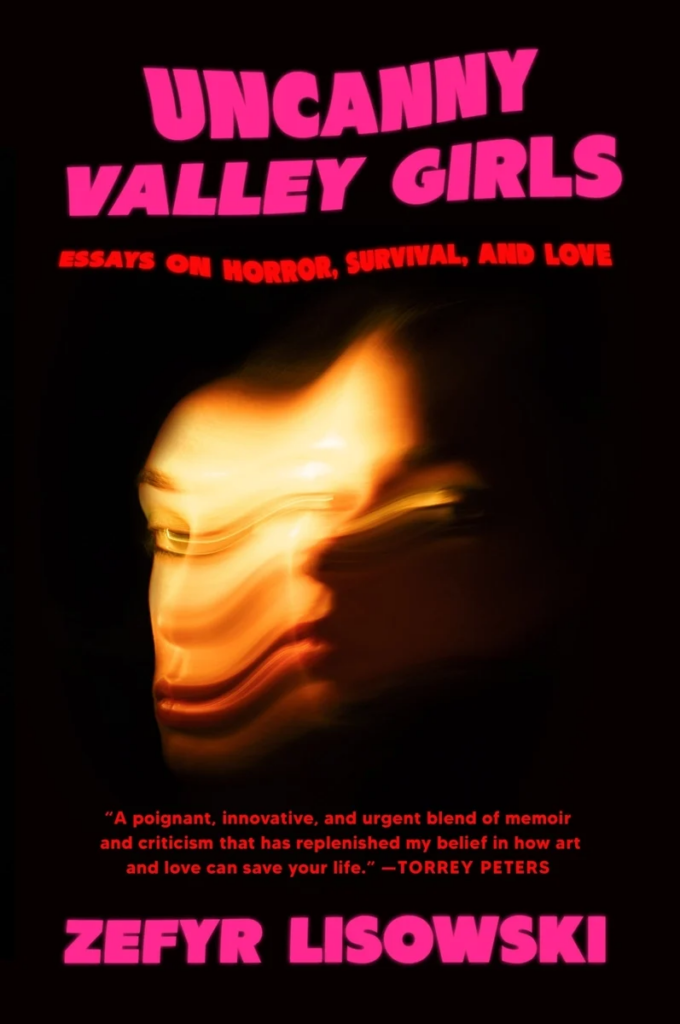

Zefyr Lisowski’s phenomenal Uncanny Valley Girls: Essays on Horror, Survival, and Love (Harper Perennial; Oct. 2025) opens with her watching Scream on her laptop as she waits to be admitted to a locked psych ward because it is one of her comfort movies.

Zefyr Lisowski’s phenomenal Uncanny Valley Girls: Essays on Horror, Survival, and Love (Harper Perennial; Oct. 2025) opens with her watching Scream on her laptop as she waits to be admitted to a locked psych ward because it is one of her comfort movies.

Culturally, we don’t often associate horror movies with helping us to live through our traumatic experiences. Lisowski’s essay collection, however, ushers in a welcome change to this view. The prologue ends with: “The horrors are how I found myself, so let’s begin there. I promise, at the end, it will all shape into care.”

This is the journey we will be on with her throughout the book and like with any masterful storyteller knowing the direction of the story doesn’t lessen our engagement with it. Framing her story with her psych ward stay allows the author to move through different times of her life because psych wards are liminal spaces.

You are both in the world and outside of it simultaneously. This makes the psych ward a kind of queer space not subject to normative time. Ghosts, I imagine, experience space and time queerly as well. Lisowski is familiar with ghosts. Her older sister, who died before the author was born, hovers, haunts Lisowski’s life and the book. But her older sibling isn’t the only apparition.

As a trans, disabled, and mentally ill woman, Lisowski shares how she only saw girls like her being punished, becoming feared phantoms in movies like The Ring, leading her to ask, “If you first identify yourself in a host of ghosts, what does it mean to live despite that?” This is the central question of the book. I love how “a host of ghosts” implies community. I have spent time in the psych ward. I also love horror movies, find comfort in them. Lisowski digs a little deeper, often presenting historical stories that have turned into legend and what that says about our current culture.

In “Our Ocean, Ourselves” we are introduced to the lore of Nell Cropsey who in the early 1900s was murdered, drowned, by her boyfriend or her father. No one knows for sure. Lisowski uses this as an effective jumping off point to weave together how ghosts and water and the murder of women interact as shown in the Japanese horror movies/ghost stories Dark Water and Ringu. One of those currents of ghosts is violence against trans women as Lisowski says, “Women pop up dead in water a lot – at least in media they do.” She says this in relation to the movies and shows like Twin Peaks but can also sadly mean the news. A scene of Lisowski swimming in a lake with a cemetery at the bottom of it is a haunting visual metaphor for this. Lisowski’s writing is so alive that it is easy to conjure the images she presents as if they are photographs or clips from movies depending on what she’s describing.

Horror movies can see us before we see ourselves fully, as Lisowski states, “They showed me how to identify a hurt before I even knew how to name my own.” This is how I felt when I learned I had borderline personality disorder. Finally, I had a name for something I had only felt for most of my life. I hadn’t expected to find community on this issue in Uncanny Valley Girls, but sometimes community can materialize seemingly out of nowhere. While watching Antichrist, Lisowski identifies with Charlotte Gainsbourg’s character “a crazy woman” as she writes, “I found a power in what I didn’t recognize yet as sisterhood.” Shortly after Lisowski sees borderline represented in Gainsbourg’s character. Borderline is not presented as a big reveal. Rather, it is another aspect of Lisowski’s life, which is the type of normalization I needed to understand that my borderline is part of my life, not my whole life.

But there’s a lot of shit you go through to get to that moment, the negative messaging internalized, “What does it mean as a sick girl to learn again and again that sick girls deserve to be punished. What does it mean as a trans child to only see a film industry’s bile spat back at you?” As many of us know, this bile can also be spit on you at home.

In the LGBTQ+ community we often hear how we are family, always in community when around each other. It’s a nice bumper sticker but people are more complicated than that. One of the things I admire most about Lisowski’s writing is that she doesn’t shy away from discussing, showing the complications a community can contain as demonstrated when she finds out as an adult that the kids who bullied her in grade school are also trans women.

Zefyr Lisowski offers a mix of understanding while still holding the bullies responsible, “The women who hurt me didn’t do so because they were trans, and yet they are still trans, and they did still hurt me. They are not my allies, and yet together we still linger in this uneasy space.” An in-between space where ghosts of what others have done to us exists. This is one example of many that shows Lisowski’s nuance and sensitivity as a writer.

One of my favorite things about Uncanny Valley Girls is that it doesn’t ignore the negative things that happen to us or our actions that we end up regretting while also showing us that our journeys do not need to end in the darkness even as it discusses suicide, transphobia, and how society wants to turn us into ghosts.

I want to return to the final sentence from the prologue: “The horrors are how I found myself, so let’s begin there. I promise, at the end, it will all shape into care.” Care is such a wonderful concept. One we’ve always needed. One we need now. Care is a choice we can make. Care says that some days will be tougher than others, but we can be kind to ourselves as we go through them.

Many self-help influencers, even some memoirs, present resolution, having overcome your ghosts as the only “good” outcome of facing your trauma. It’s a neat idea. It’s an idea that sets people up for failure because it’s a product that is being sold by people who want you to keep buying their product in whatever form that takes. Lisowski’s focus on care is the antidote to the toxicity of packaged healing. Care comes with a lot less pressure as it acknowledges what haunts us. Rough times are not permanent even if it might feel like it as you’re going through them. In Lisowski’s hands, caring for others, yourself is the radical idea that many of us need.

August Owens Grimm is an acclaimed horror writer, editor, and essayist. They co-edited Fat and Queer: An Anthology of Queer and Trans Bodies and Lives. Fat and Queer won the 2022 AASECT Book Award for a general audience from the American Association of Sexuality Educators, Counselors, and Therapists. Their work appears in, among others, The Rumpus and in the Los Angeles Times bestseller, It Came from the Closet: Queer Reflections on Horror. They coined the term Haunted Memoir. They are a 2025 Lambda Literary Fellow in nonfiction.

August Owens Grimm is an acclaimed horror writer, editor, and essayist. They co-edited Fat and Queer: An Anthology of Queer and Trans Bodies and Lives. Fat and Queer won the 2022 AASECT Book Award for a general audience from the American Association of Sexuality Educators, Counselors, and Therapists. Their work appears in, among others, The Rumpus and in the Los Angeles Times bestseller, It Came from the Closet: Queer Reflections on Horror. They coined the term Haunted Memoir. They are a 2025 Lambda Literary Fellow in nonfiction.